In last week’s column I talked about autobiographical (and semi-autobiographical) comics. This week, I’d like to take a step back and focus on one artist in particular whose books are fiction but have bits and pieces of his own life in them: Will Eisner. Eisner is often called the father of the graphic novel: he popularized the term itself, but was also a pioneer in the medium—and the most prestigious American comics award is named after him.

I’d read some of The Spirit several years ago, but these stood out to me mostly as groundbreaking in the way Eisner used the medium but not so much in the dialogue, which seemed a bit corny to me and not terribly different from a lot of other comics I’ve read. What makes them stand out is that the style of storytelling is ahead of its time, and perhaps the reason it feels familiar is because so many comics artists since have been influenced by Eisner’s work.

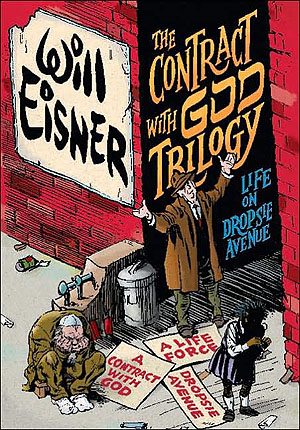

Last year I finally read one of Eisner’s more literary works, his graphic novels set on Dropsie Avenue in the Bronx. I checked out the Contract With God Trilogy, which collects three of his books: A Contract With God, A Life Force, and Dropsie Avenue: The Neighborhood. I spent the course of a few days poring over it, and it’s a masterpiece, well worth reading.

Note to parents: Eisner doesn’t shy away from showing the seedier side of life on Dropsie Avenue. There are uplifting moments, but there’s also corruption, organized crime, murder, adultery and rape, and general unpleasantness.

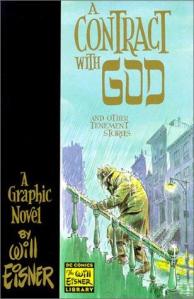

A Contract With God is a collection of short stories, starting with the title story about Frimme Hersh, an older Jewish man who has just buried his daughter and is angry with God. He has a contract, written out on a little stone, from the time he was young, and he demands that God honor his side of the contract. From there he turns from his religion and becomes a wealthy landlord, eventually working his way around to a new contract. Eisner reveals in the preface that the story was actually sparked by the death of his own daughter Alice, and this shook his faith and he was unable to discuss the loss. Eventually he wrote “A Contract With God,” but even then didn’t talk about his personal connection to the story.

A Contract With God is a collection of short stories, starting with the title story about Frimme Hersh, an older Jewish man who has just buried his daughter and is angry with God. He has a contract, written out on a little stone, from the time he was young, and he demands that God honor his side of the contract. From there he turns from his religion and becomes a wealthy landlord, eventually working his way around to a new contract. Eisner reveals in the preface that the story was actually sparked by the death of his own daughter Alice, and this shook his faith and he was unable to discuss the loss. Eventually he wrote “A Contract With God,” but even then didn’t talk about his personal connection to the story.

“The Street Singer” is about the singers who would come and sing in the alleys between tenements, hoping to coax a few coins from the residents of the building. “The Super” is a short story about the superintendent of a tenement, seen as the enemy by all the residents, and his encounter with a devious 10-year-old. The final story in the first book, “Cookalein,” is a bit longer and really showcases Eisner’s skill at juggling a host of different characters and storylines that intertwine with each other. “Cookalein” is the term for a summer resort on a farm — residents brought their own linens, cooked their own meals, did their own laundry, and it was a way for farmers to make a little extra money by renting out rooms and vacationers to take a summer trip a little more cheaply. Various characters head out of town, each with their own motives and agendas: Sam sends his wife and kids away so he can rendezvous with his mistress; meanwhile, one of his sons is in turn seduced by an older woman at the cookalein — before her husband shows up and catches them. Goldie goes off to find herself a rich husband and Benny’s hoping to marry a rich wife, both spending a lot to keep up appearances, setting up a series of mistaken assumptions that ends poorly. It’s a somewhat cynical story, but Eisner says it’s a “combination of invention and recall,” and “an honest account of [his] coming of age.”

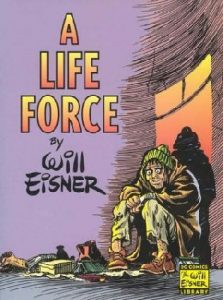

The second book, A Life Force, is also a series of vignettes, but in this case they all tie into each other. The question that crops up throughout the book is the “why” of life: what is man’s purpose? What makes him any different from the cockroach, merely trying to stay alive? It’s once again centered on the tenement at 55 Dropsie Avenue and is set during the Great Depression, and a host of different stories are told. A lot of the stories involve the Jewish community, drawing from Eisner’s own background, but he also includes Italian immigrants who owe a debt to the Black Hand; students organizing communist demonstrations and union bosses with unsavory tactics; a young bank employee who hits upon the idea to profit from bankruptcies; and the increasing difficulties Jews were facing in Nazi Germany, from the perspective of those in the U.S. Over the course of the book you really come to care about the characters and their circumstances. Of the three books in the trilogy, I think A Life Force was my favorite, because of the way everything interconnected, and the term “graphic novel” really seems to fit.

The second book, A Life Force, is also a series of vignettes, but in this case they all tie into each other. The question that crops up throughout the book is the “why” of life: what is man’s purpose? What makes him any different from the cockroach, merely trying to stay alive? It’s once again centered on the tenement at 55 Dropsie Avenue and is set during the Great Depression, and a host of different stories are told. A lot of the stories involve the Jewish community, drawing from Eisner’s own background, but he also includes Italian immigrants who owe a debt to the Black Hand; students organizing communist demonstrations and union bosses with unsavory tactics; a young bank employee who hits upon the idea to profit from bankruptcies; and the increasing difficulties Jews were facing in Nazi Germany, from the perspective of those in the U.S. Over the course of the book you really come to care about the characters and their circumstances. Of the three books in the trilogy, I think A Life Force was my favorite, because of the way everything interconnected, and the term “graphic novel” really seems to fit.

The last book, Dropsie Avenue: The Neighborhood, turns the environment itself into the main character of the book. In about 175 pages, Eisner takes Dropsie Avenue from its origins as an old Dutch farm to a small village to a block of tenements and on into a residential community of single-family homes. There are no chapter headings here — all of the stories simply follow one another without nothing more than a page break. Some of the tales last ten or fifteen pages; some are only a page or two long, just enough to depict a scene or two before moving on. Throughout the story one thing remains constant: prejudices of the current residents against the new arrivals. First the Dutch bemoan the English who are moving in and building new farmhouses; then the English dread the arrival of the Irish, who are suspicious of the Germans. New times bring new troubles: bootleggers during Prohibition, brothels, drug dealers. Italians arrive, and then Jews, and Hispanics, and Blacks … and each time there’s an influx of newcomers there are those that complain about where the neighborhood is going and move away. Eisner depicts corruption, but there are also those who fight for Dropsie Avenue, who believe that it can be a better place and work to improve the lives of its residents. Sometimes it was hard when a character showed up for just a page or two and then vanished, but there were a few characters who stick around longer and it’s fascinating to see what happens to them later in life, how attitudes change and how the character of the neighborhood develops over time.

The last book, Dropsie Avenue: The Neighborhood, turns the environment itself into the main character of the book. In about 175 pages, Eisner takes Dropsie Avenue from its origins as an old Dutch farm to a small village to a block of tenements and on into a residential community of single-family homes. There are no chapter headings here — all of the stories simply follow one another without nothing more than a page break. Some of the tales last ten or fifteen pages; some are only a page or two long, just enough to depict a scene or two before moving on. Throughout the story one thing remains constant: prejudices of the current residents against the new arrivals. First the Dutch bemoan the English who are moving in and building new farmhouses; then the English dread the arrival of the Irish, who are suspicious of the Germans. New times bring new troubles: bootleggers during Prohibition, brothels, drug dealers. Italians arrive, and then Jews, and Hispanics, and Blacks … and each time there’s an influx of newcomers there are those that complain about where the neighborhood is going and move away. Eisner depicts corruption, but there are also those who fight for Dropsie Avenue, who believe that it can be a better place and work to improve the lives of its residents. Sometimes it was hard when a character showed up for just a page or two and then vanished, but there were a few characters who stick around longer and it’s fascinating to see what happens to them later in life, how attitudes change and how the character of the neighborhood develops over time.

If you haven’t read Eisner yet, The Contract With God Trilogy is a great place to start. Eisner uses a mix of panel sizes, full-page illustrations, images that bleed into each other — even compared to most modern comics, Eisner’s compositions are wonderfully varied and appealing. What’s more, they’re easy to read: you know which panel, which dialogue bubble, comes next. It seems like that should be an obvious thing, but I still often read comics in which speech bubbles are organized poorly, or where a “creative” panel arrangement means that you can’t easily figure out the order in which they’re supposed to be read.

If you haven’t read Eisner yet, The Contract With God Trilogy is a great place to start. Eisner uses a mix of panel sizes, full-page illustrations, images that bleed into each other — even compared to most modern comics, Eisner’s compositions are wonderfully varied and appealing. What’s more, they’re easy to read: you know which panel, which dialogue bubble, comes next. It seems like that should be an obvious thing, but I still often read comics in which speech bubbles are organized poorly, or where a “creative” panel arrangement means that you can’t easily figure out the order in which they’re supposed to be read.

Of course, if you’re creating comics, then another great book to read is Eisner’s Comics and Sequential Art, his demonstration of comics principles and techniques. Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics is both inspired by and expands upon Eisner’s ideas, and Eisner’s analysis of comics is a great reference to have. For further reading, you can check out his two follow-up volumes: Graphic Storytelling and Visual Narrative and Expressive Anatomy for Comics and Narrative.

Click here for Part 4: Avoiding the Subject.