Earlier this month, I was invited (along with several other bloggers) to visit LAIKA to get an advance look at its upcoming film, Kubo and the Two Strings. I had been a couple of years ago when Boxtrolls was being made, and I was excited to see what was new this time around. Here’s an inside look at the movie, and don’t worry: I’ve tried to remove references to anything that hasn’t been seen in the trailers.

Every time LAIKA makes a movie, they raise the bar, setting new challenges for themselves and tackling bigger problems. When asked what new challenge Kubo presented to the team, producer Ariane Sutner said that one of the biggest challenges this time around was just that—the size. Most of the movie takes place outdoors, in big spaces, and the sets for this movie were considerably larger than in previous films. The set for the small village, when fully assembled, was about 80 feet long!

Since the shooting for Kubo was already complete by the time of our visit, they still had some of the sets on display, but many of the stages were already in use for their next film (which was kept entirely secret). Even with the size of these sets, some of them were digitally extended when necessary. For instance, there was a big compound with a courtyard, and the building as seen in the film is three stories high. As you can see in the photo below, the top of the building is filled in digitally.

There was another model of the exterior of this compound, made at a smaller scale, which included the entire building. All of the sets were raised on platforms and were modular so that pieces could be removed to give the puppeteers access. Dan Pascall, the production manager, said that for Coraline one of the biggest problems was that the set platforms were made of wood, and the Pacific Northwest climate meant that the wood would stretch and shrink overnight. When the crew came to shoot in the morning, sometimes the set floors weren’t aligned and they would have to spend a lot of time adjusting heights. Now the platforms are all made of steel, so they don’t have that issue anymore.

Many of the backdrops in the movie are computer generated rather than built or painted, due to the scale. It’s not just the sets that got bigger: the puppets got bigger and more complex, too—but more on that in a bit. Sutner also noted that this film has more action scenes than previous LAIKA films.

LAIKA has its own VFX department, which means that they don’t have to ship things off to another studio for effects work; instead, they can work very closely. In fact, it seemed to me from this visit that LAIKA’s films should really be called hybrid animation—there’s still stop-motion animation at its core, but there is a lot of CGI and digital work as well. With Coraline, just about everything you see on screen was actually there, on camera (though digital effects were used to remove lines, erase rigging, and so on). ParaNorman was more of a hybrid film, combining more digital effects. Kubo has entirely digital puppets: in the village scenes, where there are big crowds, digital puppets were made and added in, while the “hero” puppets (the main characters) were shot with stop-motion animation.

But Emerson explained that even with the CGI puppets and effects, a lot of the design work is still done the same way they would make a physical puppet. They pick material references for the costumes, and then base their CGI puppet designs on those references. Once the digital puppet is created, they compare it to a physical maquette placed in the set so they can rotate it around and compare the lighting.

The VFX team also uses a lot of photo references for character design (just like the physical puppet design team). Some of the extras in the movie are also physical puppets, but then crowd scenes are filled in with digital puppets. However, it’s clear that LAIKA doesn’t make digital puppets simply because they’re taking the easy route. Even the digital puppets and digital elements of the hero puppets have a lot of care put into the details.

For the characters, we got a chance to see a lot of what goes into the designs, both in the costumes and the puppets. First, Deborah Cook showed us some of her process for designing costumes. She uses photo references, artwork, and material samples as inspiration—we got to see a couple of big bulletin boards, but I’m sure there was even more that we didn’t see. For Kubo, since origami played a big part in the film, they turned to origami and kirigami (folding and cutting) for some inspiration in how things would look.

Although the main characters themselves are not made of origami, their clothing still draws from the look of it. For instance, Kubo’s sleeve has a particular crease at the elbow that looks like the paper sleeves—Cook showed us a little wire device that was placed inside the sleeves to ensure that the sleeve creased there every time, as well as another wire along the bottom that kept the pleat sharp (and allowed animators to control how the sleeve hung from the arm).

One of the things Cook showed us that I thought was really fascinating was the weighted fabric. They wanted some fabrics, like the robes that Kubo’s mother wears, to look heavy and worn. After some experimentation, they ended up with fabric glue that had some sort of metal in it, which they applied to the back of the fabric using a laser-cut stencil. The glue kept the fabric stiff in some places so it could only fold in certain places, and the metal gave it some weight. The result looks really amazing.

Georgina Hayns, Puppet Fabrication Supervisor, gave us a closer look at the puppets. The characters start off as drawings, and then sculpted maquettes—much like they usually do in both traditional 2D animation and in CGI animation. However, once the character has been designed, it’s up to the puppet fabricators to create a puppet that can be animated and move around. Most of the human puppets in Kubo were designed similar to those in previous films, as far as the armature inside. The head has a removable face (more on that later), and then the costume is put onto the puppet. This film had a couple of puppets that were particular challenges, though: Monkey was covered in fur, Beetle had four arms and an exoskeleton, Kubo’s ants had feathered capes, and there are various origami creatures that Kubo brings to life.

Beetle had a complex armature, which you can see in the photo with Hayns above, and the exoskeleton was made in such a way that the various plates slide over each other. Only the top and bottom chest plates are directly attached to the armature, and the others can flex with each other in a way that ends up looking very natural. The wings shown in the photo were designed and fabricated even though they are digitally animated in the film—this is the process LAIKA uses to ensure that anything that is digital will still match the look of the physical puppets. Beetle’s armature has 85 individual parts to it.

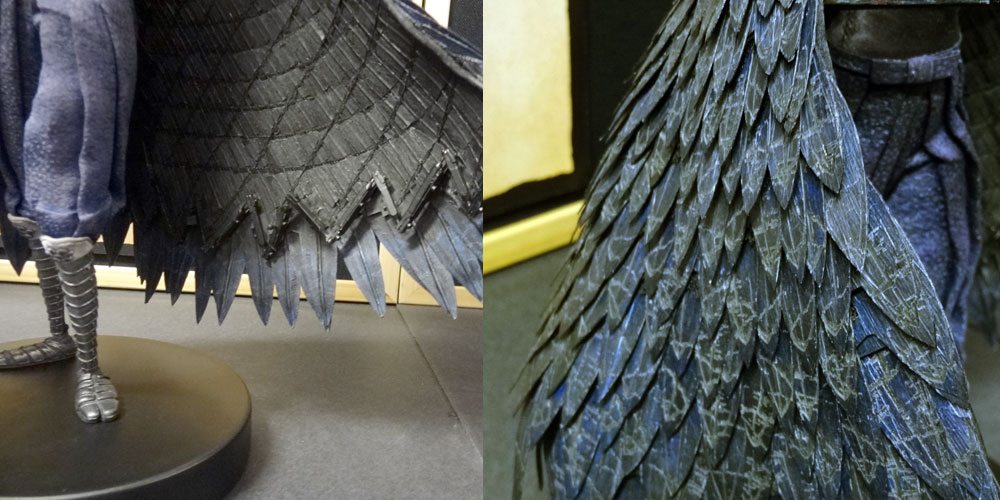

Kubo’s twin aunts are pretty creepy—you get a sense of that in the trailers. They wear Noh masks, so at least there was no facial animation necessary. However, they also wear feathered capes, and the animators wanted to be able to control the capes so they could be very expressive. Hayns’ team came up with an armature that goes along the edge of the cape with tiny ball joints. Then, the cape itself had a woven mesh made of piano wire—stiff enough to hold its shape once it was directed with the armature. Finally, the feathers themselves—hundreds of them—have wire in them, so that they can be manipulated individually as needed.

Monkey presented a particular challenge: she was covered in fur, so it was a different process than building a puppet and putting clothes on it. With this one, they built the armature, and then covered it with a body suit—this simulated muscles and sinews with stretchy fabric. Indeed, when you move the puppet, the surface stretches and flexes like skin. Then, they used a fur fabric, which was then combed and trimmed row by row to get that layered look. Monkey’s head is 3D-printed resin, to go along with the replacement faces (see below). They had a couple of Monkey puppets: one was an “action” version that had wires under all of the fur so that the fur itself could be animated. Another one was “wet” Monkey, covered in silicone paint to look slick.

In the film, Kubo uses his magic to bring origami creations to life, telling stories with them. For the models in the film, the team first started by creating creatures out of origami or kirigami. They built paper maquettes, and then deconstructed them to figure out how to create the various parts so they could be animated. They tried cardboard and paper, but the puppets would fall apart after the handling required to animate them. The final versions use Tyvek, which looks like paper but is much more durable, but then they had trouble getting the paint to hold, so it had to be dyed.

We got a peek at some of the props made for the film, and Assistant Art Director Phil Brotherton told us a little about the design sensibilities that went into them. LAIKA’s previous film, The Boxtrolls, had really complex visuals—everything had intricate patterns and a lot of colors and lots and lots of details. In Kubo, they drew a lot of inspiration from the woodblock prints of Kiyoshi Saito: A lot of things had a woodblock texture printed on them, but the physical forms themselves were not as busy as those of The Boxtrolls. One of the things that comes from the woodblock look is that sometimes textures do not follow the contours of an object—for instance, horizontal or vertical lines carrying straight across an uneven surface.

Brotherton explained that there’s a balance between what’s realistic and what fits the look of the film. One example he gave was for some burnt props—you can see a little on the right side of the photo above. They looked at what real objects looked like when they were burnt and charred, and tried making props that matched those, but then when placed within the context of the movie, they just didn’t look quite right. So the charring is more stylized, with blocks of white on the black, and it gives an impression of being charred without being actually charred.

Morgan Hay, Lead Fabricator for Rapid Prototyping, explained to us how 3D printing has been used to make the animation of the faces even better. I was familiar with this from LAIKA’s previous films, too. Stop-motion animation has been using replacement heads or faces ever since the faces were not moldable plasticine, with heads showing different expressions that can be swapped out as the animator moves the body. Of course, that makes for a whole lot of heads, particularly if you want a wide range of expressions and smooth animation between those expressions. LAIKA has been using rapid prototyping technology since Coraline, creating the needed faces digitally and then printing them out. They work very closely with the 3D printing manufacturers to push the possibilities and technology to its limits.

Most of the heads come apart at the eye line (as you can see from Monkey’s faces in the photo), allowing an even bigger range of expressions. The line across the face is then removed digitally later. Jack Skellington in The Nightmare Before Christmas had somewhere around 10,000 expressions (one per head)—Kubo’s heroes have over a million expressions. Kubo also had a set of faces that were twice as big, used for some extreme closeups of his face. Of course, since the heads were based on 3D digital models, it was easy to print them twice as large.

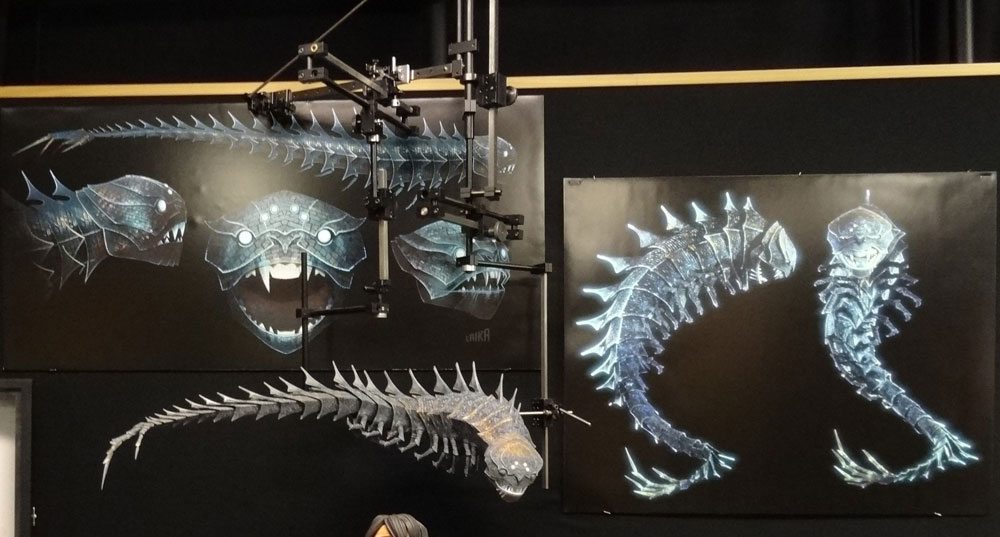

The Moonbeast is a huge flying creature that Kubo battles, and it is LAIKA’s first fully 3D-printed puppet. It’s a giant dragon-like beast with plated armor. The faces, like those of the other puppets, are replacement faces with different expressions and its tail looks like a skeletal hand. Because of the size of the beast, it was printed at half-scale, and then digitally enlarged.

Some of the Moonbeast’s scales are gold and reflective, but they still look translucent. Hay showed us how they did it: they experimented with Mylar balloons, putting them behind the translucent resin, and discovered that it would reflect the light from underneath the scale. The 3D-printed scales have a mix of translucent and opaque scales, so that when gold foil is attached underneath, some of the scales shine through. Reflective material is something that is very easy to photograph, but hard to simulate. So this is a cool trick that allows for the scales to reflect the actual light on camera, rather than having to add that digitally later.

Remember what I said about not taking the easy route?

In one scene, Kubo and his companions have to fight a giant skeleton—it seemed like a job for a digital puppet, right? But then they thought about how they would build the skeleton if they were to do it physically. This is how the VFX team usually starts: they imagine how something would function physically, so that when they design the digital effects, they match the look of the stop-motion portions. Well, as they talked about how to animate a 25-foot tall skeleton, they decided to go ahead and build it. The result: the largest stop-motion puppet ever built.

The skeleton sits on a hexapod that allows it to tilt as needed, and the arms have a complex pulley system that lets the puppeteer position the hands and let the arms and elbows follow a natural movement. The skeleton does have legs, too, but they come in a separate piece, because if the skeleton were fully assembled, it would be too tall for the room.

In the scene with the skeleton, instead of making the skeleton itself digital, they ended up using CGI to fill in the environment. The scene takes place in the Hall of Bones, which is an octagonal room. They built one physical wall, and then used CGI to make it look like 8 walls.

Here’s another example of a huge puppet: a giant underwater eyestalk. In the trailer, you see a few of these briefly as Kubo floats before one of the enormous eyes. The team built one of the eyestalks and then digitally copied it to make several of them. They showed off some of the custom-made controls for it. The tentacles on the side are made to flex and bend as if it is waving in the water—these they were able to create a movement pattern and then program it to loop. The body itself can move around, too—it’s controlled by a series of wires and cables. But to make it more intuitive for the puppeteer, they made the smaller body shape (seen in the foreground of the photo), so that the puppeteer can manipulate the rods on the smaller body to control the bigger body.

The eye is a big translucent sphere with a light inside, and there are layers of tulle inside that rotate, making interesting patterns as the light filters through. The pupil can also be controlled—they basically made a giant trackball out of a bowling ball, and when you rotate it around, the eye looks around. The final effect as it’s seen in the film is really entrancing.

At the end of the visit, we were able to sit down with Travis Knight, the CEO of LAIKA (and also the director of Kubo and the Two Strings and an animator), along with Ariane Sutner, producer and head of production, to hear a little more about the creation of the film and to ask some questions.

Knight shared that they’ve been working on this film for about five years now—animated films take a long time to create, and stop-motion films are particularly labor-intensive. He made the comment that “Good stories can change us—those are the types of stories we want to tell.” He reiterated something I heard during the tour for The Boxtrolls, that LAIKA doesn’t want to have a “house style”: he doesn’t want all their movies to look the same, but for each one to have a look that makes sense for the story that is being told. Since Kubo takes place in a fantasy world that is inspired by Japan, they used Saito’s woodblocks as an inspiration, using limited color palettes and less intricate details.

When asked about his inspirations, Knight pointed to Steven Spielberg. The first film that moved him to tears, he said, was E.T. He said he knew while watching it that it was artifice, that it wasn’t real, and yet it still struck a chord and caused real emotions—that was the moment he realized the power of film. He read about Spielberg’s own influences, and found his way to Kurosawa, whose influence can be seen in Kubo. But he also loved a lot of other things: comic books, Star Wars, big fantasy epics, Tintin, Tolkien. Kubo is a storyteller who brings his artwork to life, and it’s natural that Knight sees himself in Kubo. But, he added, so do the other animators, because when you are animating the puppets, you’re acting, and you have to put yourself into the story and the characters.

I asked Knight why LAIKA continues to do stop-motion animation, when it seems that they have built up incredible digital techniques that can rival other CGI-only animation studios. What is it that stop-motion animation adds to a film? His response was that there is “an inherent humanity that comes out of the process of making the art. The act of creating things by hand adds an element of humanity that doesn’t exist otherwise.”

He went on to say that LAIKA wants to use the best tools to move the story forward—everything should be in service of the story. But stop-motion animation is a different type of performance than other 2D or 3D animation (both of which Knight has done). With other animation, you can iterate: you can add or delete frames, you can polish things up. In 3D animation, you can change the lighting, add another prop, change the camera angle. But stop-motion animation is more like a live performance—once it’s shot, you can’t change the action easily. There’s a little more room for spontaneity, but also there are quirks of the animator that are captured and show through.

One blogger asked how LAIKA walked the fine line between inspiration and cultural appropriation: Kubo and the Two Strings has a lot of Japanese influence, but Knight is a white American. Lately there’s been a lot of news about whitewashing in Hollywood—casting white actors in roles that were originally written for people of color—and I think it’s a valid concern. During the studio tour, we learned that LAIKA had a Japanese cultural consultant who would advise them as they were creating props and sets and creating the story.

Knight said that, as an artist, he draws inspiration from many different sources: “If I could only draw inspiration from things in my own experience as a white American, then I would have a much more limited palette.” He described the work of Hayao Miyazaki: many of his films take place in Europe—but Miyazaki’s take on Europe isn’t “real” Europe; it’s an impressionistic version of Europe, made by a Japanese man who loved certain things about European culture. Knight wanted Kubo to be a fantastical version of Japan, paying homage to it but not an exact portrayal. He also mentioned that Saito’s woodblock prints were themselves influenced by Western artists—the thread of inspiration wanders through many different cultures.

Some of LAIKA’s films have been based on existing stories, and some are original stories. When asked whether LAIKA had a preference for one or the other, Knight said that they “look for great stories wherever we can find them.” They don’t have any hard and fast rule about original stories vs. adaptations, but just want to use whatever tools they have at their disposal to tell the best stories they can.

LAIKA provided this B-Roll footage showing some of the process of animation and prop creation. It’s always really cool to see some of the footage before everything is cleaned up digitally:

Kubo and the Two Strings will be released on August 19. I can’t wait!

For more on how Kubo and the Two Strings was developed check out Shannon Tindle’s tumblr http://shannontindle-blog.tumblr.com . Shannon was the creative vision behind Kubo, creating the story, designing the characters, among many other contributions to this amazing film.

Shannon Tindle was the director on “Kubo and the Two Stings” at LAIKA for 3 years. Kubo was created, written and directed by Shannon Tindle, it was a project he put over 5 years of work into only to have it stolen from him by Travis Knight. In the last year of production Shannon Tindle was removed from Kubo by Knight so that he could announce Kubo as his own directorial debut and take full director’s credit.