It is 1882, and the world is at war: a growing band of rebels, calling themselves the Restorationists, wants to free humanity from the centuries-long rule of the Old Ones. Inspired by Neil Gaiman’s short story of the same title (really good–read it!), A Study in Emerald is a fascinating tabletop game that puts Sherlock Holmes into the world of H.P. Lovecraft.

At a glance: A Study in Emerald (Second Edition) is a game by Martin Wallace for 2 to 5 players, ages 13 and up, and takes about an hour to play. It retails for $59.99, and is published by Treefrog Games (and distributed in the USA by Grey Fox Games, who provided my review copy). The game involves hidden roles and direct attacks against other players; I think the rules are complex enough that I wouldn’t necessarily play it with younger players unless they are fairly experienced gamers. It has a Lovecraftian horror theme (this time, not played up for its humor) so it is creepy but generally is not so terrifying that young kids need to be ushered out of the room while playing.

A Quick Note: This is the second edition of A Study in Emerald. The first edition was funded on Kickstarter in 2013, and quickly sold out and became very difficult to acquire. This edition has completely new artwork and enough rules changes to warrant a separate entry on BoardGameGeek. However, I have never managed to play the first edition so I’m unable to comment on specific differences between the two. From what I’ve read, this version has been simplified somewhat but is still fairly similar.

Components

- 1 game board

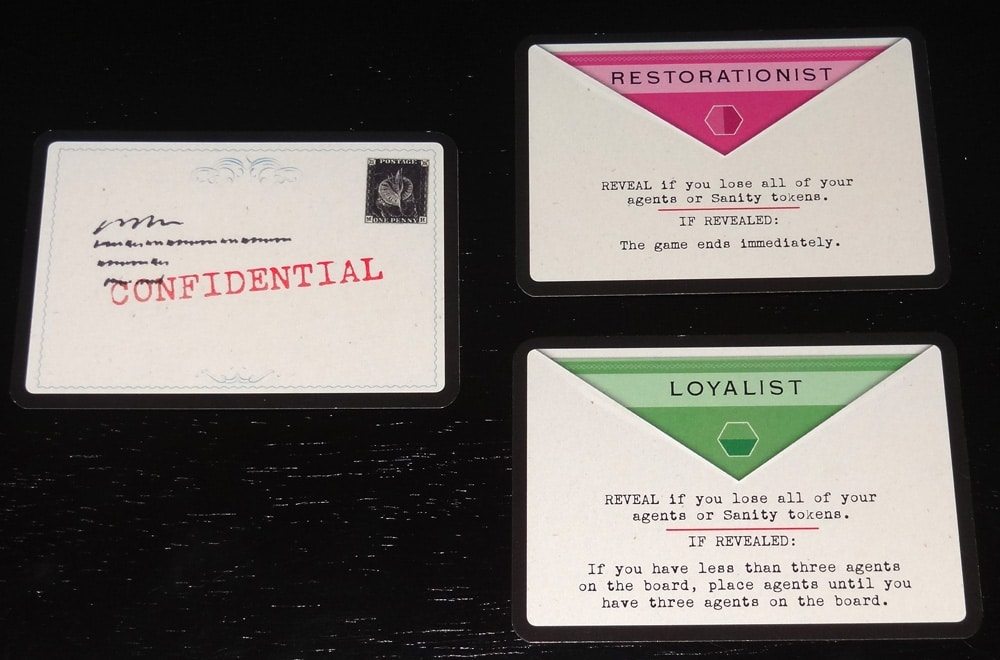

- 6 Secret Identity cards

- 66 game cards

- 9 City cards

- 9 Royalty cards

- 2 track markers

- 15 Sanity tokens

- 1 Sanity die

- 6 Zombie meeples

- 5 sets of player pieces:

- 1 Victory Point disc

- 10 Influence cubes

- 10 Agents

- 10 Starting cards

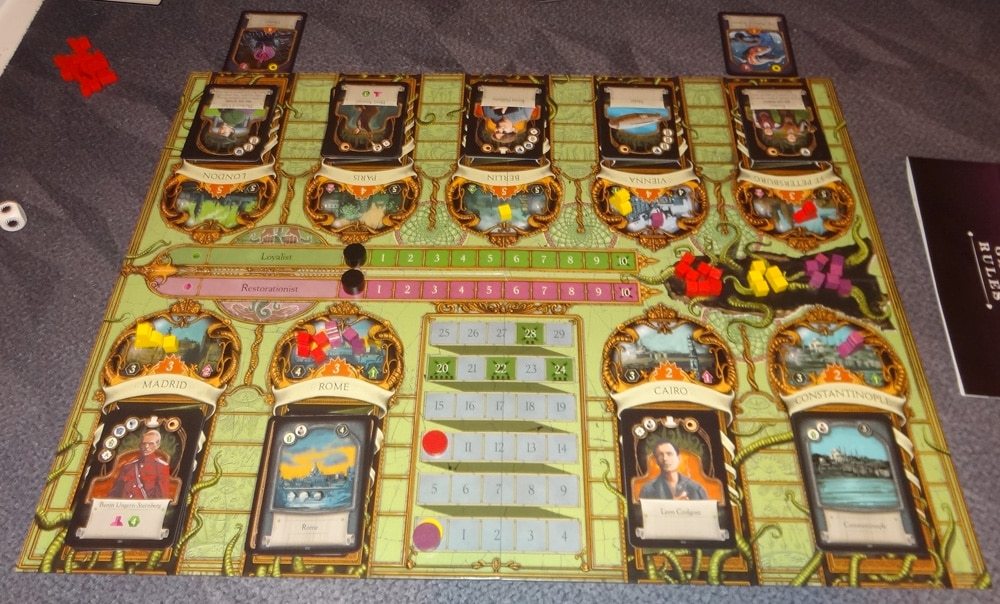

The game board is large, with a lot of elaborate decorations (and lots of tentacles). I personally like the way it works, but it is a bit busy. I’m particularly a fan of the “Limbo” section of the board, which looks like a black tear in the board with tentacles reaching out of it.

The cards are decent quality–easy to shuffle–but the black background and borders are showing some wear after several plays. Each player’s cards have a colored background matching their wooden pieces, and each player is named after a day of the week.

The artwork is nice but the iconography on the cards is (in my opinion) kind of ugly and unintuitive. For instance, the movement icon is a segment of railroad track, but it really looks like a ladder. Another is that the Sanity icon (which indicates that you need to roll the Sanity die) is one of the few icons with a yellow background instead of white… even though the Sanity die (and Sanity tokens) are all white.

The Agents are small wooden busts–a silhouette of a man with a hat, which matches the “Agent” icon that appears on some of the cards. The Agents aren’t uniform in size–some are slightly larger than others, and one was missing a shoulder. The discs and cubes seem to be fine. The Zombie meeples are fantastic–little grey figures with their heads slumped to one side–but there’s actually only one card in the entire deck that uses them (assuming it even shows up), so I’ve never actually had occasion to use them yet. It does seem strange to have special pieces that are used only for a single card in the deck.

The Sanity die is a small wooden die with rounded corners, with the swirly black Sanity icon printed on four of the six sides.

How to Play

The goal of the game is to score the most points; although there are two factions in the game and you want to work with your teammates, you still want to have the highest individual score.

It helps to know at least a little bit about the theme: Loyalists are those who support the Old Ones, who are now the “royalty” in this world. Restorationists are the freedom fighters trying to overthrow the Old Ones–even assassinating them thanks to the recent discovery of dynamite. Loyalists foment war because the psychic energy feeds their masters, and Restorationists are inciting the population to throw off their shackles. As the rulebook says, “to some observers the difference between the two aims is difficult to discern.” Players are moving about, using their influence to recruit various characters to their teams, and then trying to carry out their secret aims. When Restorationists go insane, they shoot themselves, preferring to die than live in madness. When Loyalists go insane, nobody can really tell the difference.

To set up, each player takes a set of player pieces and cards. The Loyalty cards are shuffled and one is dealt to each player face-down–the rest are returned to the box without looking at them. Look at your own Loyalty card but do not reveal it. Each player places 5 Influence cubes in Limbo, and 3 Sanity tokens on their Loyalty cards. Each player’s score marker is placed on the scoring track on the board. Shuffle your starting cards and draw a hand of 5 cards.

The board setup is as follows: each city location on the board gets its corresponding City and Royalty card, plus a number of cards (based on the number of players) randomly dealt from the deck. Each city’s cards are individually shuffled and placed face-down on the location, and then the top card of each location is turned face-up. If any Royalty are revealed, they are moved off the board next to the city space, and the next card is revealed. Each player places 5 of their Influence cubes in Limbo. The two track markers are placed at the “0” spot on the Loyalist and Restorationist tracks on the board.

Decide on a first player, and then each player in clockwise order gets to place an Agent on the board in any location. Repeat this so that each player has two Agents on the board total–Agents may share locations with other Agents.

A Study in Emerald is a deck-building game–all players have their own decks of cards and discard piles. When you are told to draw a card, it comes from your own deck, and if you run out of cards to draw, you shuffle your own discard pile together to form a new deck. Most cards that are acquired from the board will go into your discard pile, eventually making their way back into your hand.

A note about scoring: Throughout the game, certain cards or actions will grant points immediately. However, some points are only valuable for Loyalists, and some are only valuable for Restorationists. Since everyone’s identity is secret, you move up the scoring track no matter what, and then at the end of the game when Loyalties are revealed, you will decrease your score if necessary.

Now the game begins.

On your turn, you get two actions. You take an action by playing any number of cards from your hand that have that action symbol on it and then discarding them to your own discard pile–the more of that icon you played, the more you can accomplish with that single action.

Actions include:

- Claim cards

- Place Influence cubes

- Retrieve Influence cubes

- Move Agents

- Move faction markers

- Perform an assassination

- Card action

- Discard cards

- Pass

Claim cards: To claim a card from a city space, you must have more pieces total than any other player, and at least one of them must be an Influence cube. Basically, you’re spending your influence to acquire something, whether it’s a person or equipment or the city itself. Each “claim card” icon you play may be used to acquire a card from one city, as long as you meet the requirements. After claiming a card from a city, all of your Influence in that city goes into Limbo; all other players’ Influence is returned to the players.

Also: you may only claim cards as your first action of the turn, so you have to already have the majority when your turn begins. If the card claimed has an Agent symbol on it, immediately place one of your Agents from your supply into that city. (You just recruited that person.) If the card has a yellow Sanity symbol on it, immediately roll the Sanity die; if you roll the symbol, lose 1 Sanity. If the card has a hexagon on it, immediately move yourself up the scoring track equal to the number shown.

Whenever a card has been claimed, the next card is revealed. As in setup, whenever a Royalty card is revealed, it is moved off the board next to the city.

Place Influence cubes: Place one Influence cube per icon played from your supply into one city. You may not overpay by playing more cards than you have cubes in your supply (except in the case of a card that has 2 “place influence” icons on it).

Retrieve Influence cubes: Retrieve one Influence cube per icon played from anywhere on the board, whether in city locations or in Limbo, and place them into your supply.

Move Agents: Move one Agent per icon played. Agents may move anywhere on the board.

Move faction markers: Some cards have “up” arrows with numbers on them, either green (Loyalist) or pink (Restorationist). You may play any number of these up arrows (in both colors, if you wish), and move the faction markers up accordingly. Everyone scores points based on the difference between the two faction markers. So if they are 3 spaces apart, everyone scores 3 points on the score track. If, later, the other faction marker moves up and they are only 2 spaces apart, everyone loses a point. At the end of the game, when Loyalties are revealed, only the faction that is ahead will get to keep the points.

Perform an assassination: You may assassinate other Agents in a city or a Royalty card that has been revealed. To assassinate, you must have more pieces in that city than any other player, and at least one must be an Agent. (Influence is all well and good, but somebody has to pull the trigger.) You may perform one assassination per icon played.

Assassination also requires bomb points. First, you play the cards that have the “A” icons to indicate how many assassinations you are performing. Then, for each one, you must pay the correct number of bomb points: to kill another Agent, you must meet the requirement shown on the location on the board; to kill Royalty, you must meet the requirement shown on the Royalty card. Each Agent in that location counts as 1 bomb point; bombs shown on the cards played for the “A” icon do not count.

The “A” cards are permanently out of your deck, and set aside near your Loyalty card for the rest of the game. If you kill Royalty, you will immediately gain the points shown (keeping them at the end of the game if you are a Restorationist) and also make a Sanity check. The Royalty card is set near your Loyalty card. If you kill another Agent, that Agent is immediately removed from the board and placed on the “A” card. You score 3 points–but you will only keep those points at the end of the game if you are a Loyalist and the killed Agent belongs to a Restorationist.

Card actions: Many of the cards have special actions printed on them. You may play a card for its action instead of any icons that may be on it. If the card is a “One-Use Action” then it is removed from the game after you use it for its action. If it is a “Free Action,” then it may be played at any time during your turn and does not count as one of your two actions.

Discard cards: You may discard any number of cards from your hand.

Pass: Sometimes you have nothing you want to do or are able to do.

After you have taken your two actions, draw back up to 5 cards.

If you ever lose your last Sanity or you have no more Agents on the board, you immediately reveal your Loyalty card. If you are a Restorationist, the game ends immediately. If you are a Loyalist, the game continues–and, at any time you have fewer than 3 Agents on the board, you immediately place 3 Agents in any spaces of your choice.

The game also ends immediately if either of the faction markers reaches the “10” space, or when any player reaches a set number of victory points (based on the number of players).

Once the game ends, everyone reveals their Loyalty cards, and scores are adjusted. Any victory points you earned during the game (according to the cards you have in your deck and in front of you) that do not match your Loyalty card are subtracted from your score. Also, if your faction is behind on the track, you lose points equal to the difference. Finally, if your faction is behind on the track, everyone in your faction loses 5 points. (Ties go to the Restorationists, so Loyalists need to be strictly ahead in order not to lose those points.) The player with the highest score wins.

The Verdict

Neil Gaiman’s short story is a fantastic piece of fiction, and it’s easy to see why it would make a great setting for a game. Unfortunately, I didn’t know about the game until well after the Kickstarter campaign was over, and despite a few attempts I never managed to acquire a copy of the original or even play it. So I was very glad to see a second edition had become available, and I’ve had a lot of fun playing it (even while getting some of the rules wrong).

I really like the way that the mechanics of the game fit the theme. You exert influence to acquire equipment or sway people to your team–but then you’ve called in your favors and you have to build your Influence back up in order to acquire something else. The cities have different thresholds for assassinating other Agents, making it easier to to pull off your dark crimes in Constantinople than Berlin, for instance. The characters in the game–a mix of people from Sherlock Holmes stories and real-life figures–do tend to have abilities that make sense. For instance, Sigmund Freud restores your sanity, and Irene Adler can turn another player’s Agent to your side.

The game is an odd mixture of area control and deck-building (actually, a little bit like Web of Spies), in which you’re only able to acquire a card when you have control of the city. In this case, the two types of control–Influence and Agents–are spent differently and lead to some interesting tactics. Agents are not spent when you purchase a card, and they also count as bomb points. However, they’re also much harder to acquire–aside from a few special cards, the only way you get a new Agent on the board is by acquiring a card with the Agent symbol on it. Influence can be retrieved from Limbo (and is returned to you automatically if somebody acquires a card from a city where you have Influence), but it is also quickly spent. If you get into an arms race with another player and you pile a lot of Influence in one place, you will spend it all when you acquire a single card.

The fact that you may only buy a card as your first action makes acquisition tricky. As soon as you signal your intention to buy a card by placing Influence, everyone else at the table has an entire round to interfere with you–moving Agents to that location, placing their own Influence, and so on. They don’t have to outnumber you, either–if anyone matches your number, it prevents you from acquiring that card. So there’s a lot of jockeying for position–but eventually somebody either runs out or gives in, because there are more locations than any one player can control at any given time.

The scoring system is a little odd: giving everyone points and then subtracting them later seems more troublesome than just giving points to the right people at the end of the game–but the difference is that giving everyone points moves you closer to the end-game threshold. You can trigger the end of the game by moving a faction marker far enough, or even by gaining some points that you know you will lose, if you think you’ll still have enough points to win the game.

Early on it can be hard to figure out what teams people are on, but there are some actions that tend to give you away: if you assassinate Royalty, chances are pretty good that you’re a Restorationist. Assassinating another player is only worth points if you’re a Loyalist (and the victim is a Restorationist), but that doesn’t mean that Restorationists won’t go on the offensive simply to gain control of a city. And, although it doesn’t happen often, a Loyalist could even assassinate Royalty simply to prevent a Restorationist from getting those points.

You don’t want to give away your position too quickly, but at the same time it’s important to figure out who’s an enemy and who’s an ally. The last-place team penalty is a strong motivating factor for figuring out who’s on your team. Losing 5 points is significant, so it’s important to note who is in last place on the scoreboard before you end the game–can you risk losing 5 points? I haven’t played enough yet to know whether it’s best to reveal yourself right from the start. It seems that Loyalists have more of an advantage to playing openly, but Restorationists have a bounty on their heads so they may need to sneak around some more.

One odd thing about the hidden roles is that you shuffle all of the cards and deal them out, regardless of the number of players. So if you have 2 or 3 players, it is possible that all the players are on the same team–but you won’t know it immediately. Even in a situation where it’s a 3-vs-1, it’s not guaranteed that the single player will lose, because there are some advantages to being the only person who’s going after Royalty, for instance. Plus, it may be more likely that one of the team of 3 will be the lowest-scoring player, which helps the team of 1. It’s yet another reason why it’s important to find your teammates quickly.

The fact that you only use a portion of the cards in each game (the most you’ll use is 45 of 66, in a five-player game) means that the game can be different each time depending on which cards are in the deck and even the order in which they appear. Although some cards are more powerful than others, it simply means that players will devote more resources to compete for them. So rather than a set price (as in many deck-building games), the price of cards in this game is really set by supply and demand. I’ve seen a card acquired for as little as 1 Influence, and I’ve witnessed a massive battle (with loss of Agent lives) over a single card.

My primary complaint about the game are that I don’t feel the iconography is very well done. Some of the things are pretty intuitive: a cube with a down arrow means you place cubes on the board, and a cube with an up arrow means you pick it up. But the “acquire card” symbol is two cards, with a tiny “1st” printed on one of them–that’s to remind you that it can only be your first action, but it’s just odd that there are two cards there. And the “A” for “assassinate” just seems kind of lazy.

The game can, at times, feel slow if players are after the same cards–you’ll spend all your turns just pulling Influence out of Limbo and investing it all in one city. You may spend your turn feeling like you didn’t accomplish much. On the other hand, once all the players understand the rules, the game can play fairly quickly because there are short turns like this from time to time.

The rulebook is okay but not terrific–some of that may be my own fault, but I like to think that I’m generally pretty good at reading rulebooks and I still got a lot of rules wrong even after playing a few times. I think part of it is that the way that cards are used is a little different from typical deck-building games. In most games, each card you play is an action; here, each action can consist of any number of cards–but you only use one type of icon across all of the cards you play for that action.

Overall, though, I have thoroughly enjoyed A Study in Emerald. It’s a great mix of mechanics that really fit the theme. Fans of Sherlock Holmes and Lovecraft (and Neil Gaiman) will love this mash-up. And one of these days, those zombies are finally going to show up.

A Study in Emerald is available from Amazon.

Disclosure: Review copy provided by Grey Fox Games.

You really aren’t missing out on much in never having played the first edition. It is more complex, but also VASTLY more convoluted. The complexities really don’t add that much to the game over this version at all.

That’s what I’d heard, that the second edition had been streamlined, and from what I can tell this is probably the version I would prefer. I know some people have strong opinions about the artwork between the two versions. I like this board better, but I do like the sepia-toned cards from the first.

The board is definitely easier to manage as a board game component, but as a piece of artwork, I did like the old board better. But last I checked, boards in boardgames are meant to be used, not just looked at 🙂

I could honestly go either way on the cards. I agree that they might be a bit too bright for the theme of the game, but it isn’t too bad.