There are few things that get people riled up more quickly than politics and religion—but as it turns out there are plenty of comics that deal with the two. And as Ghandi once said, “Those who say religion has nothing to do with politics do not know what religion is.” They may not be the best topics for dinner conversation, but they have certainly inspired some great comics.

I’ve already mentioned a few comics that also touch on religion in the previous posts: Art Spiegelman’s Maus, Craig Thompson’s Blankets, Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, and Will Eisner’s Dropsie Avenue stories. Here are several more.

The Book of Genesis — R. Crumb

Robert Crumb is a giant of the underground comics (or “comix”) scene, and has achieved a lot of recognition for his comics even though he has entirely worked outside of mainstream comics. He was the first artist to illustrate Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor. A lot of Crumb’s comics featured sexual themes and he’s well-known (and controversial) for drawing very sexualized women. So I was somewhat surprised when, back in 2009, Crumb published a comic book version of The Book of Genesis (through W. W. Norton, no less)—he wasn’t exactly somebody I would’ve expected to illustrate the Bible. I remember in an interview in The New Yorker that Crumb said he’d originally thought about doing a satire—but that the text seemed so bizarre to him that he decided in the end to approach it as a “straight illustration job,” letting the text speak for itself. And since Crumb illustrated the entire book of Genesis (including the lengthy genealogies), with plenty of research, the irony is that this artist who does not believe the Bible is “the word of God” has probably spent more time with the book of Genesis than many who do.

Regardless of your religious beliefs, Crumb’s take on Genesis is worth reading (with, as the cover states, “adult supervision recommended for minors”). The familiar stories are there, of course: Adam and Eve; Noah and the ark; the Tower of Babel; the beginnings of Israel through Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; the story of Joseph and his amazing technicolor dreamcoat. But you don’t get a watered-down kids’ picture book version of these stories—you get the whole thing, every word of the original text (drawn from several sources). You also get some of the stories that generally aren’t taught in Sunday School (at least not until you’re older), like Shechem and Hamor’s revenge for the rape of their sister Dinah, or Tamar’s unconventional solution to losing her husband (and chance to have children).

Crumb includes commentary at the back, not on every single chapter but on significant portions of it. In particular, Crumb explains a little of Savina Teubal’s theory of the matriarchal order that may have existed early on, one that was overtaken and hidden by the patriarchal society later. It’s a theory that may explain some of the things that occur, like Abraham claiming that Sarah is his sister or the way Rebekah and Jacob disagree over which son should get the birthright.

There was, as expected, some controversy over the book’s publication, but I think overall it was overblown. Some called it “scandalous” but there’s really nothing in the book that wasn’t there in the first place—perhaps it’s just the shock of actually seeing nudity associated with the Bible? Of course, outside of the commentary, one might argue that Crumb also hasn’t added anything to the book of Genesis, either—like the way Chris Columbus took a very literal approach to the first Harry Potter movie. Some people loved that it was exactly the way it was written; some people were disappointed that there wasn’t something more. At any rate, Crumb’s take feels like a faithful (pardon the pun) visual depiction of what he calls “a powerful text with layers of meaning that reach deep into our collective consciousness.” I haven’t been able to find any evidence that he’s working on the book of Exodus next—looks like he’s been busy with The Graphic Canon—but I’m sure his take on Moses would be striking as well.

(For further reading, consider Stan Mack’s The Story of the Jews. While it’s something between a comic book and a heavily-illustrated story, it traces 4,000 years of Jewish history and is a nice (if sometimes one-sided) overview of Jewish traditions. Oddly enough, God plays a very small role in the book and Hanukkah is never mentioned.)

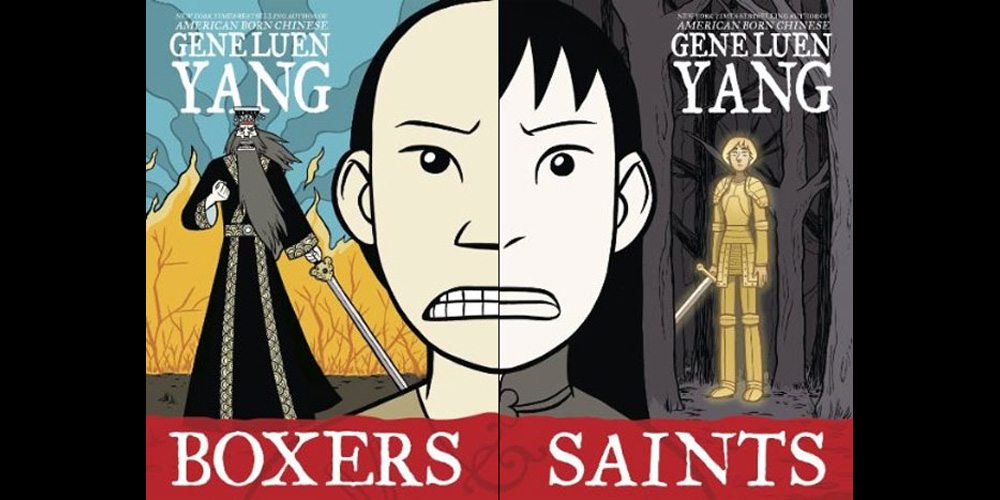

Boxers & Saints — Gene Luen Yang

This title is actually a two-book set from one of my favorite comics creators, Gene Luen Yang. The two books tell a story of the Boxer Rebellion, in which Chinese peasants (the Boxers) warred with European missionaries and Chinese Christians. Yang, a Catholic himself, was torn by the question of who the protagonists were in this story, particularly because in many instances ethnic Chinese were warring against each other. The result is this pair of books, Boxers from the perspective of the Chinese villagers and Saints from the perspective of the Christians. Boxers & Saints is due out in September, but I got an advance copy and found both sides of the story fascinating. (The books are available for pre-order now.)

Boxers centers around a boy named Little Bao, who seeks to defend his country from the influence of the “foreign devils.” He and his fellow “Boxers” harness the power of the ancient Chinese gods to battle the foreigners—but it is difficult for him to know how to deal with the “secondary devils,” the Chinese converts. Saints focuses on Four-Girl, a girl who isn’t even given a proper name at birth and is believed to be cursed. So when she discovers the Christians, she decides to join them simply to fulfill her role as a “devil”—but eventually embraces the faith. She has visions of Joan of Arc, and struggles with her destiny: is she to lead the Christians in arms against the Boxers?

The two books have some overlap but for most of the story the two main characters take totally separate paths. It’s interesting that, although both characters have visions that guide them and direct them, neither of the religions or cultures is portrayed as totally right or totally wrong. I didn’t feel like the books generalized the motivations behind all Boxers or all Chinese converts to Christianity; they were accounts of two specific fictional characters. I really didn’t know much at all about the Boxer Rebellion before now; Boxers & Saints may be a good jumping point to learn more.

The Rabbi’s Cat by Joann Sfar

The Rabbi’s Cat tells the story of an old Algerian rabbi and his daughter, from the point of view of his cat. Early in the book, the cat eats the rabbi’s parrot and gains the gift of speech—and then uses it to lie. But as the story continues, the cat’s personality continues to develop. It’s a fascinating look at Judaism in the 1930s: Arabs and Jews coexist in Algeria but neither of them are fully accepted by the French. The book has a sly humor (befitting a sneaky cat) and raises some intriguing questions about faith. There is some strong language and sexuality in a few sections that makes it inappropriate for kids, but it’s a wonderful tale about a father and daughter, coming to terms with a changing world.

The sequel, The Rabbi’s Cat 2, gets into some interesting issues surrounding race and religion—a Russian Jew shows up in Algeria, and wants to go on a journey to Ethiopia, where he has heard of a tribe of black Jews. Rabbi Sfar has his eyes opened: his knowledge of other cultures—even other Jewish cultures—has been limited to his own experience, and he is very skeptical about things that he hasn’t experienced himself. There are discussions about whether paintings are allowed (the Russian Jew is an artist), and on a meta-level I suppose this could be applied to the very medium of comics itself.

The artwork in The Rabbi’s Cat is sometimes detailed and realistic, sometimes more loose and fluid, and I’ll admit the inconsistency sometimes bothers me a little. However, overall the book is lovely, and portrays aspects of Judaism that are probably less familiar to many American readers, particularly goyim like me.

How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less — Sarah Glidden

Now here’s one where you really start to see the intermingling between religion and politics. In 2007 Sarah Glidden, a non-religious American Jew, took a “Birthright Israel” tour. The idea is to bring young Jews from around the world to visit Israel, free of charge—in the hopes that they will come out of the experience with a better understanding of Israel. However, Glidden a self-professed liberal, and she resists much of the pro-Israel information she gets from the tour guides as propaganda. Yes, she is Jewish, but she wants to balance the story, to hear things from the Palestinian view as well.

How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less is her account of her birthright trip, and it is a fantastic look at Israel that gives some new perspectives. Glidden is never entirely won over to the pro-Israel camp, but her experience is different from what she expected. As she realizes later, perhaps she went into the trip simply hoping to reinforce her own negative stereotypes about Israelis. What she comes away with is a much more complex understanding of this embattled territory and the people who live there.

The illustrations are great, with just enough detail to help you put yourself in Glidden’s place, and for anyone who wants a closer understanding of Israel and Palestine this is a fantastic way to start—Glidden also includes a brief bibliography, a glossary, and a “very incomplete” timeline of the history of Israel at the back of the book. She even describes her own mild “Jerusalem syndrome.” I like that this book isn’t trying to convince the reader of a particular viewpoint: it’s more a reflection of Glidden’s own questioning of herself. There are some scenes where she pictures herself as judge, jury, prosecutor, and defender in a trial: the case of “Birthright Is Trying to Brainwash Me vs. Birthright Is Actually Pretty Reasonable.” She may not be totally “fair and balanced” even by the end, but she acknowledges that it’s not as black and white as she wishes it could be.

Templar – Jordan Mechner, LeUyen Pham, Alex Puvilland

Ah, the Knights Templar—a fertile source of many a conspiracy story, from The Da Vinci Code to Assassin’s Creed. They’ve been accused of all sorts of incredible things, but the true story of their downfall is full of intrigue and politics and scandal. Templar, a brand-new graphic novel written by Jordan Mechner (the creator of Karateka, among other things), is … not actually that story.

Well, sort of. In 1307, the king of France ordered the arrest of all of the Templars. The ensuing trial was a political show put on by Guillaume de Nogaret, the king’s chief minister, who almost makes McCarthy look like a nice guy. The knights were falsely accused, tortured, put to death—casualties of politics and victims of religion. This much is fairly true.

Mechner weaves those accounts into a tale of a few not-so-pure Templars who survived the Inquisition. This small band of knights come up with a scheme to steal the famed Templar treasure from the king. It is, Mechner admits, adding to the vast sum of nonsense that has been written about the Templars in the past. But it weaves in the true story, and it is a lot of fun to read.

The artwork by Pham and Puvilland is excellent—and there’s a lot of it. Templar is a 470-page hardcover, beautifully put together by First Second Books. Read it, and the next time somebody brings up the Templars, you might be able to contribute some facts to the conversation … or contribute some more to the conspiracies.

(Templar will be released this Tuesday, July 9.)

Habibi — Craig Thompson

Craig Thompson’s breakout book, Blankets, dealt with some of his own struggles with Christianity. Habibi is his fictional tale which draws from the shared roots of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. I hesitate a little to include it here because I’m still a little undecided how I feel about the book—the artwork is beautiful but the book is a little overwhelming. Habibi is a story of great divides and juxtapositions: the modern and the ancient, the first world and the third world, paradise and hell. The story incorporates foundational stories of religions, told through a parallel tale of two child slaves who are then separated and encounter very different experiences.

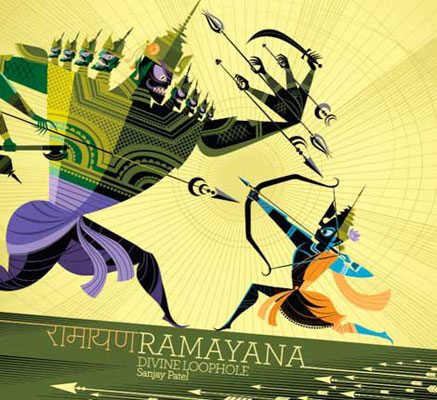

Ramayana: Divine Loophole — Sanjay Patel

I’m sure you’ve noticed that so far all the comics I’ve mentioned deal with the Big Three of western religion: Judaism, Christianity, Islam. I’ll admit: as an American Christian, I have limited experience with other religions, and even less in comics about other religions. For the most part, I’d say the overwhelming majority of comics I read don’t address religion at all, or if they do it’s only in a very cursory manner—and in any case, they’re most likely from a Judeo-Christian worldview.

Ramayana: Divine Loophole is a notable exception. It’s based on the Ramayana, an epic Hindu story about the giant ten-headed Ravana and Vishnu’s blue-skinned avatar, Rama. (No, not that sort of blue-skinned avatar.) Sanjay Patel is an animator and storyboard artist at Pixar, and although he was raised by Hindu parents and the Ramayana was part of his cultural identity, he never really knew exactly what it was about. After publishing The Little Book of Hindu Deities, he was inspired to write and illustrate this version of the Ramayana. He’s cut the story down, leaving out some details and stories but making it accessible to noobs like me.

Patel’s illustrations are flat and angular, and they remind me a little of Charley Harper‘s work, though the subject matter is certainly unfamiliar. Patel goes for a simply-stated prose in the retelling, making this something you could read to your kids, with contemporary language. Certainly there are scenes of violence and some can be a little gruesome, but no more than you would encounter in Greek mythology (or, for that matter, in the book of Genesis). The back of the book has profiles of the various characters, a little bit of geography showing Rama’s path, and a few pages of sketches for the book. My one complaint is that the book could have used a bit of proofreading, because I spotted several typos scattered throughout. Overall, though, Ramayana: Divine Loophole is a wonderful window into a culture that was pretty unfamiliar to me.

There are some other comics which touch on religion that I’ve enjoyed though I wasn’t sure if they warranted an “official” entry here. Animal Crackers by Gene Yang is a somewhat bizarre book that has talking animal crackers and some weird sci-fi elements, but in the end deals a bit with Yang’s own faith and beliefs. I’ve enjoyed a lot of Yang’s other comics as well and Roman Catholicism isn’t something that has been a recurring theme in any of his other books. Doug TenNapel is another comics artist who incorporates his Christian faith into some of his storytelling, but often in very unconventional ways. Creature Tech is a good example of this: although at times it can seem a bit heavy-handed, it also has some really fun and wacky creatures.

Click here for Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3. The next post in the series is Part 5: Truly Super Heroes.

Nice! This is the first I’ve heard of Boxers and Saints, and as a big fan of Gene Yang, I can’t wait! I’m also looking forward to Templar; and as a half-Palestinian American Christian, I’m very interested in How to Understand Israel. Thanks for the recommendations!

You’re welcome! Boxers & Saints isn’t out yet, so I’ll probably mention it again later in the fall when it’s actually due, but it’s already up for pre-order, and I highly recommend it. I have to admit that Templar is largely fun adventure story rather than truly “serious,” but there’s some truth peeking through the fiction, and the intersection of politics and religion is certainly real enough.