I have never played tabletop gaming sensation, Root. I’ve always wanted to, but I don’t really have any friends (or family) close by who want to try it with me. I loved the look and theme of Root, which is why I was thrilled to have the chance to look at Root: The Roleplaying Game.

What is Root: The Roleplaying Game?

I’ll start off by saying this isn’t an RPG for all RPGers. It’s a great game, but one for those who love the narrative elements of roleplaying games. Most of the players with whom I spent many years roleplaying, wouldn’t understand how to play Root tRPG. Or rather they would understand, but wouldn’t want to do so.

There’s probably a whole series of posts that could be written about types of games and types of players, but I would describe my friends as old-school, traditional, players. They like to number crunch and work out the best permutations for their characters. They liked to fight things and steal all the treasure. They enjoy solving puzzles and the mechanics of moving a story forwards, but not so much the actual telling of the story.

I think, perhaps, this is quite common for those of us who are in and around 50. These days, however, there are a huge and diverse number of systems that put storytelling at the heart of the game. Games that require a more collaborative relationship between GM and players. Root: tRPG is such a game. It promotes, nay, requires, that the story evolves on the fly. The creation of a common narrative is a collaborative effort and the reason for playing.

Root: tRPG is set in the same world as Root the board game; “The Woodland.” Denizens of the Woodland are anthropomorphized woodland creatures; typically, but not exclusively, birds, rabbits, foxes, or mice.

The Woodland is made up of a network of “Clearings.” Each Clearing has its own hierarchies, rivalries, and affiliations. Each one might (if the story requires it) have interdependencies on neighboring clearings. The Woodland has a number of competing ruling factions and each clearing, generally, will have loyalty to one of these factions.

The players form a group of Vagabonds. Brave adventurers who roam from clearing to clearing in search of excitement, to earn a crust, or maybe just to cause trouble. There are lots of reasons creatures might become a vagabond and defining this for your character is an important part of character generation in Root: tRPG.

You can check out the Root: tRPG quickstart guide on Drivethru RPG.

How do I Generate a Character?

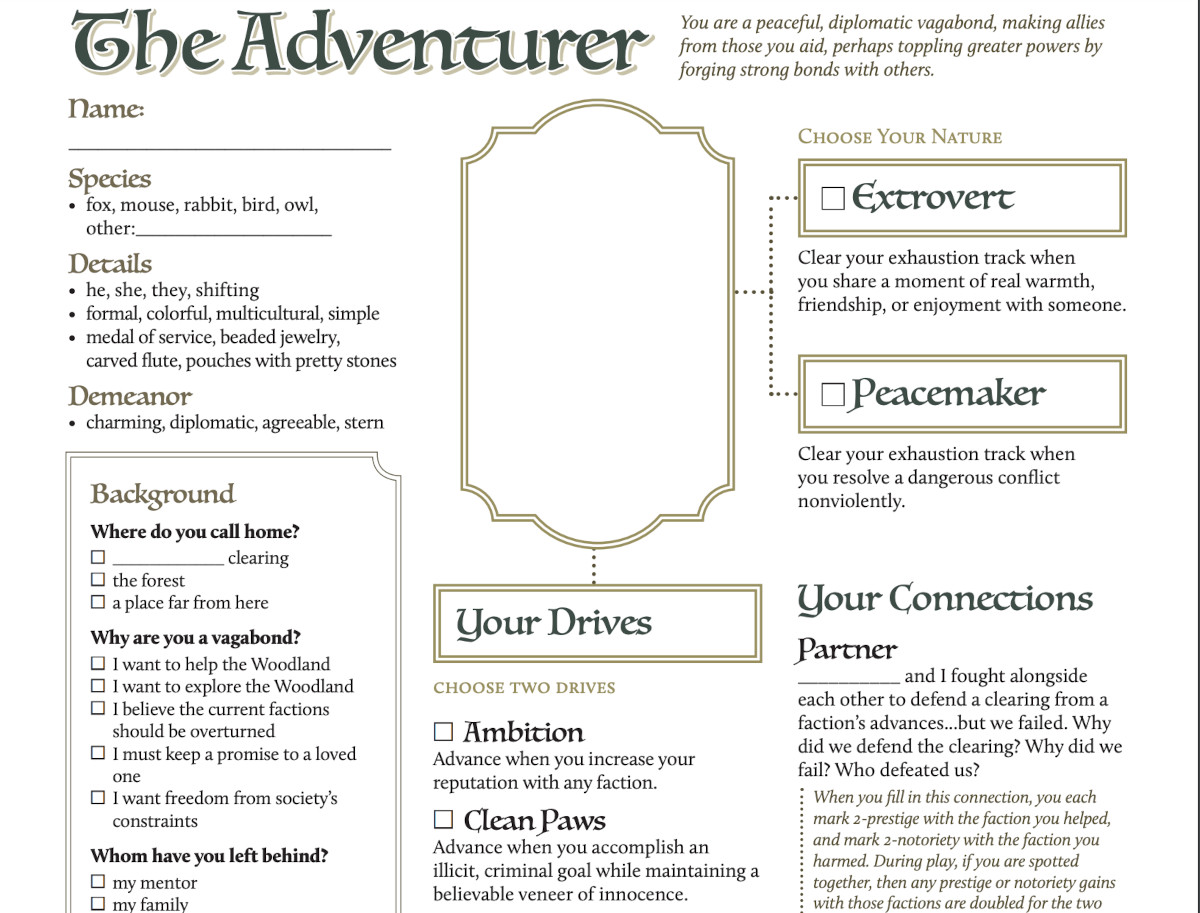

Every character in Root: tRPG has a “Playbook.” Archetypes of Vagabonds that exist inside the Woodland. Character generation begins by choosing your Playbook. This is a collaborative effort with the other members of the group, as each vagabond should use a different playbook. Not only that, the process invites you to create connections between your character and two others in the game. This is done as a collaborative process and begins the forging of the party as a group of individuals that are intrinsically linked.

There are 9 different playbooks in the core rules and they’re called cool things like The Ranger, The Ronin, and The Harrier. New playbooks can be found in the “Travelers and Outsiders” supplement.

There’s no dice rolling involved in creating a character. Each playbook has a predefined set of skills and stat bonuses. Similarly, each playbook has a predefined set of “skills,” “feats,” and “moves.” Variation arises because not all skills, feats, and moves can be chosen. Players pick a subset of each (the number of which is defined by the playbook) and the choices made define the sort of Ranger, Ronin, or Harrier you might create.

You can find print-friendly Playbooks, here

Your Move Punk!

One of the defining character features in Root: tRPG are the “Moves.” These are special abilities or areas of expertise that your vagabond may have. You can only pick a subset of the available moves from your playbook, which again helps make your Ranger different from any other.

During a game, your moves are used as conversation starting points. If you can justify to the GM why you should use your move in a current in-game crisis, the GM will allow you to do so. In the abstract, this way of doing things feels wooly and imprecise. It’s one of those rules that will appeal to the storytellers rather than the number-crunchers.

Crunching Those Numbers.

There is very little number crunching in Root: tRPG. Much of the story progression is carried out through conversation. Often your stats might inform how NPCs interact with the characters, but the GM never rolls dice. How the world develops entirely depends on the PCs actions.

The PCs do roll dice, particularly when making a move. Even so, there is still very little number-crunching. Rolls consist of rolling 2D6 and are usually based on a playbook characteristic. Players will add or subtract any buffs or debuffs they have in the relevant stat. Rolls that total 10 or more are a total success; exactly what the PC wanted to happen, happens.

Rolls of 6 or less or a failure. Something bad is likely to have happened and the GM will relay the consequences of failure.

It’s rolls of 7-9 that provide the most interesting gameplay aspects, but perhaps also the hardest paradigm shift for GMs and certainly the place where a GM has to be comfortable in evolving the storyline. Rolls of 7-9 are a success, but they are not an unqualified success. Perhaps you escape the trap, but you leave behind evidence that you have been there. You successfully scale a wall, but your pack snags on the brick and bursts open. You blag your way into the enemy hideout, but once you’re in you bump into somebody who recognizes your true identity.

This system offers up a wealth of storytelling possibilities but requires a GM who is happy to think on their feet.

The Best Rule of any RPG, Ever?

Peril and danger are represented via an interesting mechanic in Root: tRPG called “harm.” There are several harm tracks on a PC’s character sheet and during the course of a session, you’ll mark checkboxes as bad things happen to you. If you mark all the boxes in a given harm track, something catastrophic is about to occur.

Harm tracks are Depletion, Exhaustion, Injury, Wear, and Morale.

The depletion mechanic is my new favorite ever RPG mechanic. It represents those little bits of kit that all roleplaying parties need to have with them. Torches, Rope, Rations, Iron Spikes, you know the sort of stuff. Instead of discovering partway down an abandoned mine that none of you remembered to buy any torches, you can say to the GM, “I knew I was coming down a mine today, so obviously, I brought a lantern and something to light it with.” Assuming the GM agrees (and you haven’t just suggested you brought a motorboat or something), you can mark off depletion, and lo, you brought that item with you.

Having just played in a session of another game, where I completely forgot to pack rope, which I was obviously going to need where I was going, I found myself wishing every roleplaying game ever had the depletion mechanic.

The other harm tracks are relatively self-explanatory – Exhaustion marks your ability to put one foot in front of the other on your quest. If you deplete it, you must take a rest or risk collapsing where you stand. Injury is much the same but for physical damage. A fully depleted injury track does not kill you, but one more blow probably will.

Wear measures how well your equipment is holding up. That rope that’s taut against the corner of the castle wall isn’t going to hold forever. Morale is an NPC-only track. Adverse circumstances affect NPCs too and they might desert their posts or decide they don’t want to help the PCs anymore, depending on circumstances during the game.

Running Your Games.

The last 60 or so pages of the book are for the GM’s eyes only. They detail how to run games. How to set up your woodland environment and fill it with populated clearings in which conflict and shenanigans can occur. Much of this is standard “How to GM” advice, but it is very modern and inclusive and marks Root: tRPG’s place as an innovative medium in which to tell your stories.

At the end of the book is a sample clearing with outlines for several adventures set inside “Gelilah’s Grove.”

As I’ve said before, running games of Root: tRPG is quite different from games of old. The GM has to be comfortable with a narrative, collaborative style. Reading this in rules format can feel a little abstract and for a long in the tooth GM like myself, a little bewildering.

The best way to learn the system is probably to throw yourself into it. It might push you out of your comfort zone but if you have a group of people who want to play Root: tRPG they’ll want it to succeed and for that to happen they’ll have to work with you. As you progress, you’ll work out how players’ “moves” interact with the story and how best to weave their success and failures into a compelling collaborative narrative.

Together you’ll create the legend of an amazing troupe of animal vagabonds as they become fabled heroes of the Woodland Realm.

![]() To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

Click here to see all our tabletop game reviews.

Disclosure: GeekDad received a copy of this game for review purposes.