Help your village survive the winter: store up enough supplies for the winter, and beware of bandits and creatures. And while you’re out there, see if you can find that mysterious star that fell from the sky…

What Is Fire for Light?

Fire for Light is a cooperative adventure game for 1 to 4 players, ages 10 and up, and takes about 60–90 minutes to play per session. It’s currently seeking funding on Kickstarter, with a pledge level of $99 for a copy of the game. There are additional pledge tiers available that include expansions and the miniatures pack. I think the game could be played by kids since it’s a cooperative game, but probably best with some adult guidance because there are a lot of rules to keep track of.

Fire for Light was designed by Will Sobel and published by Greenbrier Games, with illustrations by Jake Morrison.

New to Kickstarter? Check out our crowdfunding primer.

Fire for Light Components

Note: My review is based on a prototype copy, so it is subject to change and may not reflect final component quality. The prototype only included components for the prologue and first chapter.

You can check out the components graphic on the Kickstarter page, but a lot of what’s included is actually not pictured because of the nature of the game. It’s narrative-based, and as you play through the chapters you’ll open up packets that include more components for that part of the story.

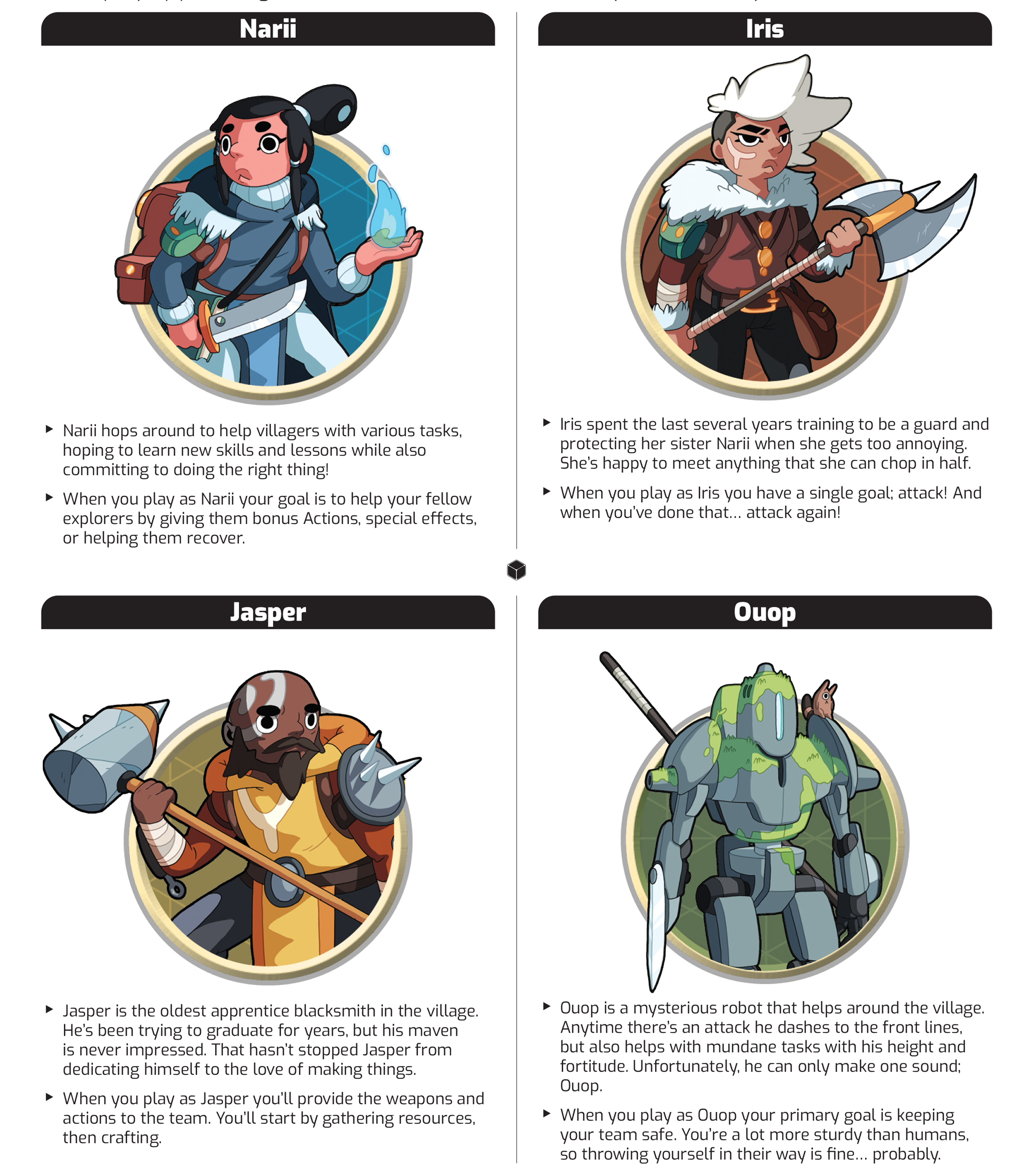

So, rather than a full component list, I’ll give more of an overview. You get 4 hero miniatures; all of the enemies will be cardboard standees unless you spring for the miniatures pack. There are large hex-based map tiles, a lot of cards (both standard-sized and tarot-sized), a bunch of cubes, cardboard resource tokens, and some custom dice.

There are also storage boxes so you can save each character and the village itself in between sessions, so that you can easily separate out the item cards, traits, and other components for each player.

The illustrations for the game are by Jake Morrison, who also did the artwork for Brew, and I really enjoy his style. It has the look of an animated cartoon, and is really fitting for this fantastical world. I’ve gotten a peek at some of the enemies you’ll face later in the game, and the artwork is excellent.

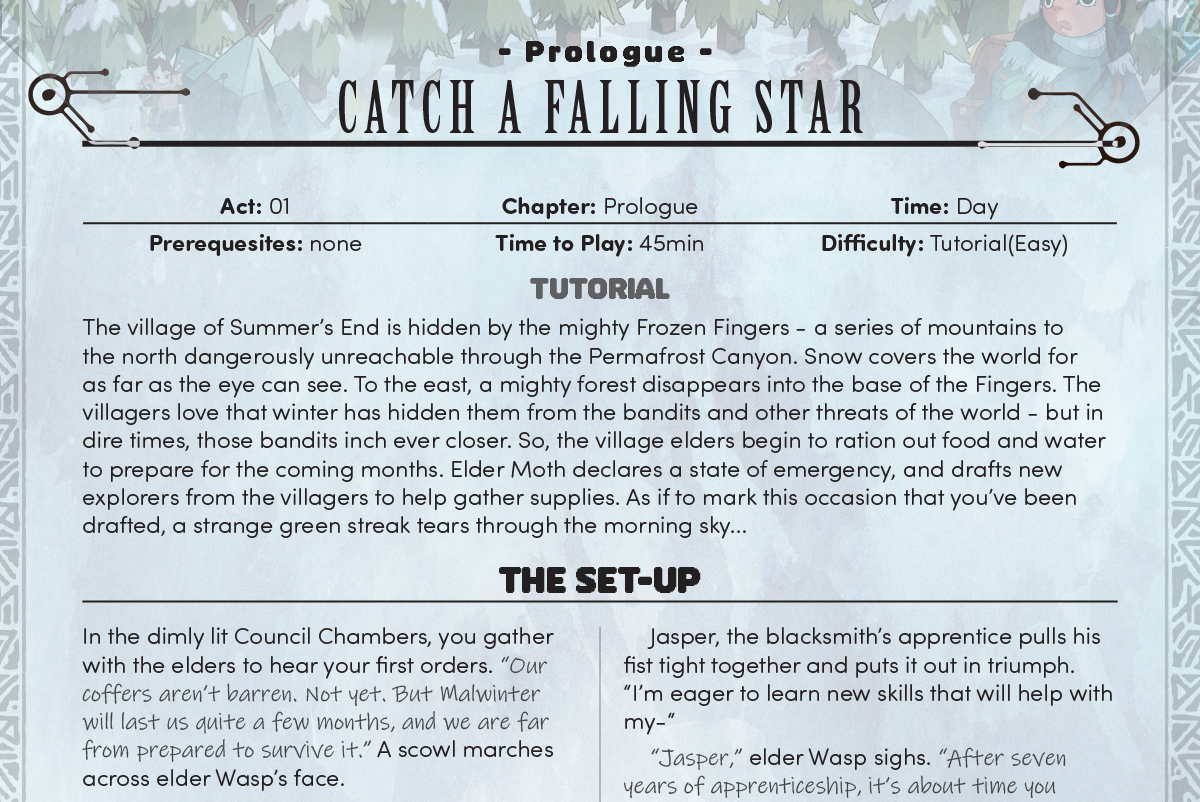

A key component is the storybook: each chapter includes both the story and instructions, including the map setup and any special rules in play for that chapter. There are also pages where you’ll record things: items you’ve collected, or decisions you’ve made, for instance—these may be referred to by later chapters. You can read the prologue and first chapter here, though be warned that this will give you a few spoilers for those sessions.

How to Play Fire for Light

You can download a copy of the rulebook here.

The Goal

The goal of each session is explained in the chapter, so it varies from game to game.

Setup

The specific setup for each session is explained in the storybook as well, but there are some general concepts that carry over. There’s a campfire board that tracks a few different things: the light dial (with day and night options), the team’s spirit level, the blueprint row of items available to be crafted, and some campfire actions.

Below the board is the awareness track, which indicates the order that players and foes will act. You always use all four characters in the awareness , but for the non-player characters, there’s a secondary version of the card that has some actions printed on it. Whatever foes start on the map are also placed in the line, and if new foes appear during the game, they’ll be added as well.

Each character has a player board and some starting items, and the player board lists how many action cubes you start with.

Finally, the storybook will tell you how to set up the map, made up of some number of large hex tiles. Skull spaces will have enemies, and there may be other points of interest, marked with the storybook tokens. (For instance, in the first chapter, the green storybook indicates the location where the falling star landed.)

Gameplay

Players and enemies take their actions in order based on the awareness track, and then there’s an environment phase after everyone has acted.

When it’s your turn, you spend your action cubes on the various actions printed on your board and your cards. If you use actions on a card, you “equip” it, and it will be discarded at the end of the round; often, actions on a card must be taken in a particular order. You’ll be able to move around, gather resources like wood and stone, and attack foes. Each character has a different mix of actions, and some characters are better at supporting others (to give them additional action cubes or unstartle them). And since you’ll be discarding equipped items at the end of each round, it’s important to use the Rest action from time to time to get cards back.

You can spend an action and a wood to build a campfire, which then makes the list of actions on the campfire board available: again, these have to be taken in descending order, but you can take any action that is currently open while you’re at the campfire. Crafting (usually done at the campfire) lets you spend collected resources to craft items from the blueprint row.

Players can also team up if they’re in the same space by spending spirit: other players may place cubes on their own actions, but things are resolved as if the active player is doing them. This can help you get better odds when fighting an enemy, for example.

When it’s an enemy’s turn to act, you just follow the actions on the card—each enemy has its own programmed behavior. For instance, the Bandit Scout will first try to attack a player in its space, then move toward the nearest explorer, and then startle explorers in its space (flipping over the awareness card, which has a lower awareness level).

Whenever you take damage from enemies, you have to discard cards from your hand: each card has a shield value. If you can’t discard enough cards, you get exhausted, which costs the team spirit and basically loses your character a turn.

Some of the map tiles also have special locations marked with an alphanumeric code—if you explore in these regions, you read the section in the storybook with that code, which will often include some more story and further instructions. The same thing goes if you reach a storybook token—you read the pertinent section of the book.

After you’ve reached the end of the awareness track, players must survive the environment: you’ll roll dice based on the light dial and compare it to the number of action cubes you have. If you roll too high, you take exposure damage, which means you lose an action cube for the rest of this session.

At the end of the round, if the campfire was lit, it is extinguished. Any player with leftover action cubes gets additional temporary awareness, which could move them forward on the awareness track. Finally, you adjust the light dial and start the next round.

Game End

Each chapter has its own end conditions. For instance, in the prologue, the story ends when you’ve found the strange meteorite and made a decision about what to do with it. It can also end if everyone is exhausted or you run out of spirit—though of course that’s not great.

Why You Should Play Fire for Light

I actually first heard of Fire for Light way back in 2018, when Walter Barber from Greenbrier Games showed me a very early prototype at Gen Con. At the time, it was going to be an app-supported game, but there wasn’t yet much he could show me. Well, a lot has changed since that initial peek—Barber has since left Greenbrier Games, and Will Sobel was brought on to work on the project, and it got a total overhaul. It now uses a printed storybook rather than an app; since I hadn’t gotten much info on the gameplay itself in 2018, I don’t have any comparison for what changed there. I’ve played through the prologue and the first chapter, and also chatted with Sobel a little about some of what appears later in the game.

The story itself is about a village called Summer’s End, and they’re preparing for the winter. Dangers lurk: roaming bandits, wild creatures, and the cold itself. Needing more resources, the elders have recruited a team … but they don’t seem overly pleased about the volunteers. Two of them are daughters of an elder—one is a village guard and the other, while enthusiastic, doesn’t have as much experience. Jasper is the blacksmith’s apprentice … and has been an apprentice for seven years. Finally, there’s Ouop, a strange robot that can only say its own name; none of the villagers aside from Jasper seem to like it much.

Your first quest is to go investigate a meteorite, but the elders disagree about what to do once you find it: offer it at the statue of the Lady of Fire, or bring it back to the village to use as fuel or materials for weapons?

As you play the game, you’ll record various things on the summary pages—for instance, what you decide to do with the meteorite—and later chapters may use that information to direct the story. It can feel a bit like reading a choose-your-own-adventure story, but instead of simply getting a page number when you make a choice, other things can happen as well: maybe you find an item, maybe some enemies appear, maybe you mark something down on the summary page that will only become significant in a few chapters down the road. I liked how the story can even take current circumstances into account: there was one instance where exploring a location had two possible results, depending on whether it was daytime or nighttime.

Some of the decisions you make during the game will give you trait cards—these start off in your hand for future sessions, and are one of the ways that your character develops and evolves over the course of the campaign. Meanwhile, the foes will evolve as well, through mutation cards that affect their behavior. It’s not a legacy game exactly, since you don’t destroy or modify components (other than writing things down in the summary), so presumably after playing you could reset it, and make different choices the next time around.

The game will also include some boss fights in the form of adversaries, printed on the tarot-sized cards. Like the regular foes, they’ll have a programmed set of behaviors, but they also have additional effects. Not only that, but as you battle, you’ll progress through the adversary’s set of scheme cards, which change what it does. Sobel said he really wanted it to have the feel of boss fights in videogames where the boss’s behavior shifts depending on how much damage it has taken.

Certainly, what I’ve seen of Fire for Light barely scratches the surface of the game, and it’s intriguing enough that I want to see more. The two chapters I’ve played so far are fairly short, despite the “60–90 minutes” advertised, but I imagine that as you progress there will be longer chapters as well.

Since the game is story-driven, a lot rests on the strength of the narrative and how much you enjoy the writing. I know the parts I read in the storybook weren’t entirely complete yet and it felt a little rough. I liked the storyline and what I’ve seen of the characters so far, but I wasn’t quite as impressed with the dialogue. (In particular, a lot of dialogue was cut off mid-sentence, and it was hard to know how much would get filled in later and how much was just intended to be the writing style.) I was reading the chapters aloud to my group, so for me the text really needs work well as a spoken story.

Over the years, I feel like I’ve gotten more interested in campaign games and exploring stories (though I still play plenty of games that are just standalone sessions), so I’m eager to find out how Fire for Light plays out!

For more information or to make a pledge, visit the Fire for Light Kickstarter page!

Click here to see all our tabletop game reviews.

![]() To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

Disclosure: GeekDad received a prototype of this game for review purposes.