Travel across the Andes with your trusty llamas to deliver wool and colorful dyes to the villages.

What Is P’achakuna?

P’achakuna (which means “textiles” in Quechua) is a pickup-and-delivery game for 2 players, ages 8 and up, and takes 30 to 60 minutes to play. It’s currently seeking funding on Kickstarter, with a pledge level of 39 Swiss Francs (about $43 USD) for a copy of the game; additional pledge tiers include a larger cloth bag and/or a plush llama as extras. The theme is family-friendly and there’s no reading involved in the gameplay (once you’ve learned the rules); I’ve played the game with my 7-year-old and she was able to learn the rules quickly, though she’s not quite as good yet about thinking through long-term tactics.

P’achakuna was designed by Moreno Vogel and Stefan Kraft and published by Treeceratops, with illustrations by Johanna Tarkela.

New to Kickstarter? Check out our crowdfunding primer.

P’achakuna Components

Note: My review is based on a prototype copy, so it is subject to change and may not reflect final component quality.

Here’s what will come in the game:

- 6 Frame pieces

- 54 Terrain tiles:

- 24 Neutral

- 15 Mostly Mountain

- 15 Mostly Valley

- White Village Center tile

- 42 Demand tiles

- 6 Llama meeples (3 per player)

- 57 Resource tokens (1 gray, 8 each in 7 colors)

- Cloth bag (not pictured above)

- Assembly plan (not pictured above)

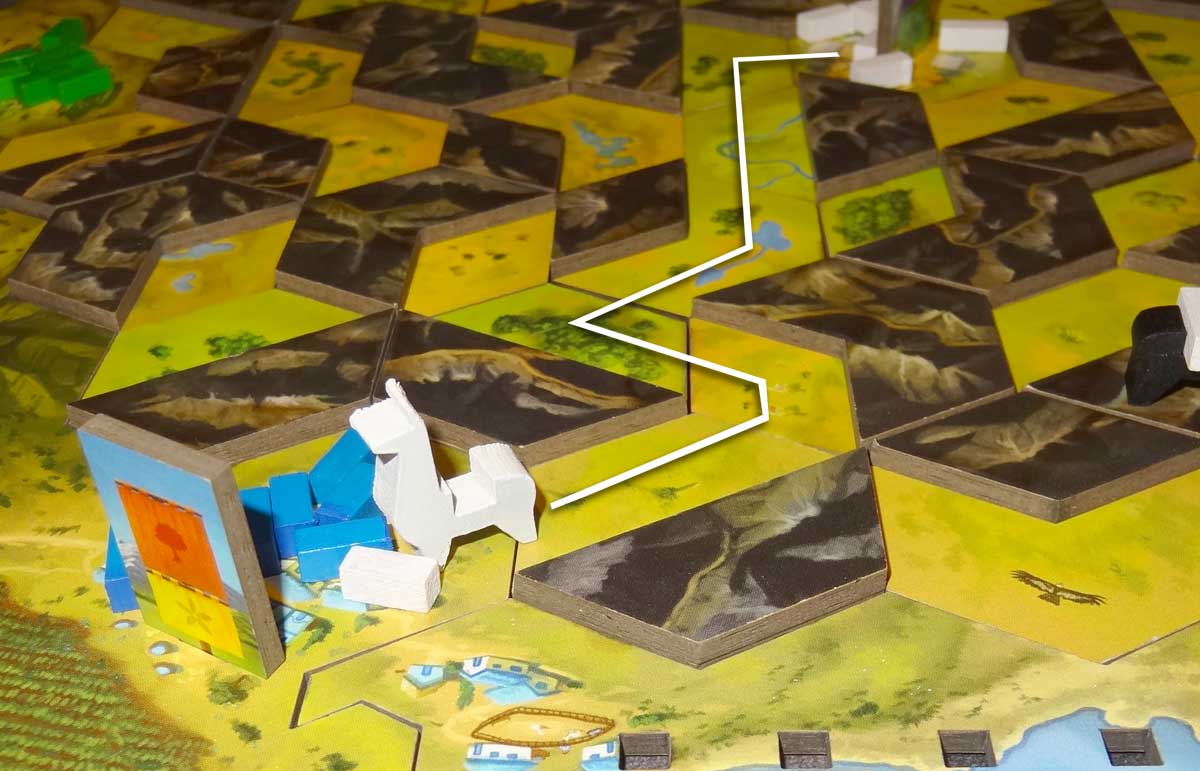

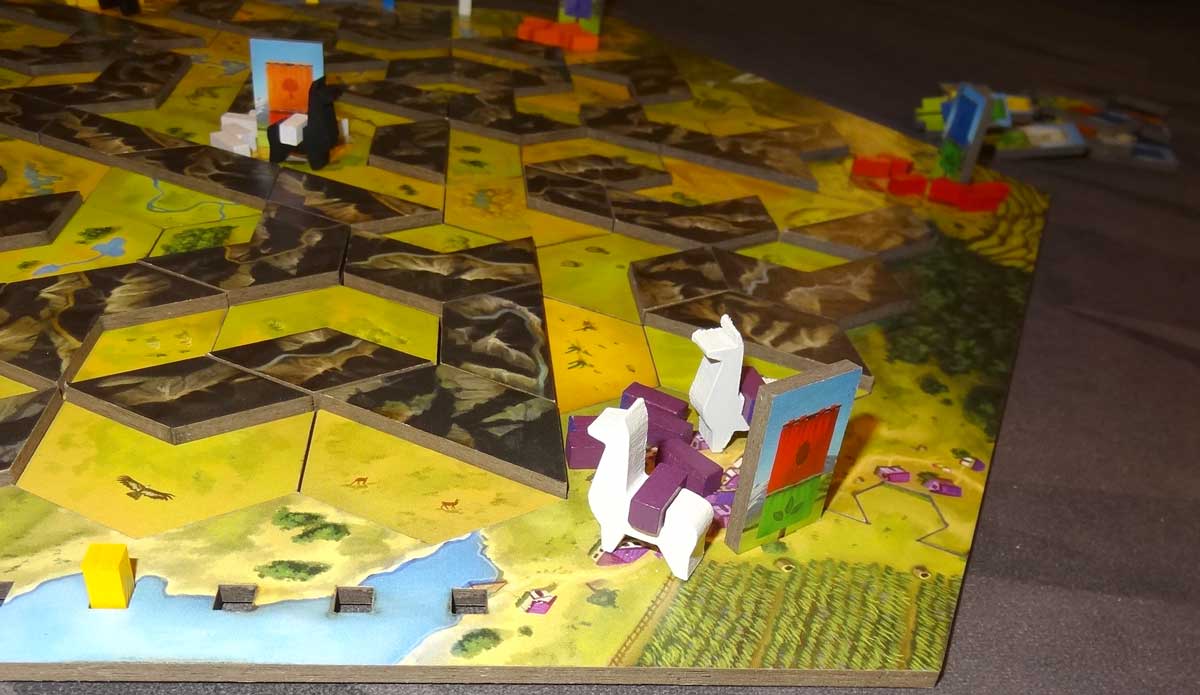

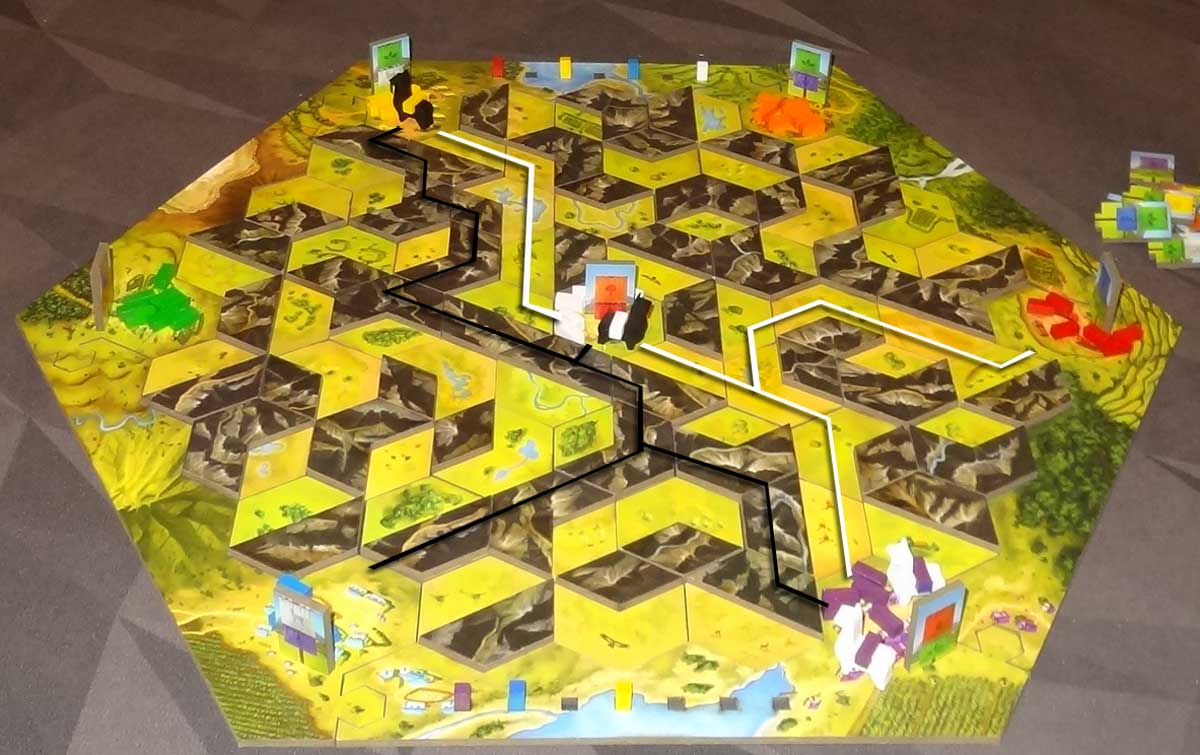

The board is made up of the terrain tiles, set into a hexagonal frame that goes together like a puzzle. The frame itself has six villages of different colors in the corners, and there’s one village tile that goes into the center of the map as well. The terrain tiles are dual-layered: the valleys are green, and the mountains are black and grey. The mountains are a thick, chunky later so there’s a clear demarcation between mountains and valleys.

The assembly plan is a full-sized map showing the assembled frame and the orientation of the terrain tiles; you can refer to it while setting up, or just lay out the tiles on top of the plan. The prototype version was printed on separate sheets of paper and taped together, so it didn’t lay as flat on the table so we didn’t set up on top of it. The finished version should be a professionally printed poster instead.

The finished game will include a handmade cloth bag from Bolivia, celebrating the idea behind the game’s theme. The bags made of locally produced fabric and paid fairly, through the Luz de Esperanza project that gets young people off the streets so they can finish their schooling and also learn a profession. (The prototype used a simple canvas bag, which you’ll see in some of the photos.)

Optionally, you can pledge at the higher tiers to get a larger cloth bag to store the game itself, as well as some small handmade llamas from Peru, which support the Suyana Foundation.

The llama meeples are really cute, with a rectangular cutout in their backs that can hold the resource tokens, which extend out to the sides. The tokens in the prototype weren’t entirely uniform, so some of them fit loosely and some were tighter, but hopefully that will be less of an issue in the finished game so your llama won’t lose its cargo during its journey.

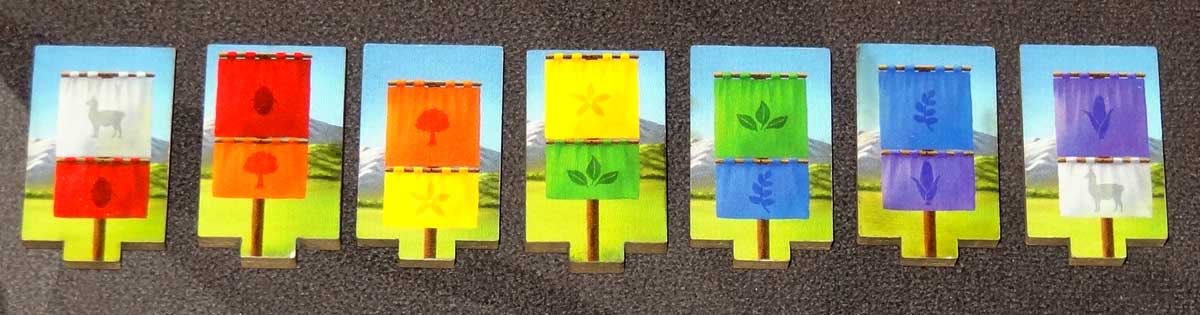

The demand tokens look like banners, made to stand vertically in slots in the board itself. Each one has two colors on it, and each of the colors has a unique icon, tied to the thing being traded. The white is for wool and shows a llama, and the rest all represent the source of the various dye colors: red made from cochineal beetles, orange made from Yanali tree bark, purple made from purple corn.

The icons could also help with color-blind players, though the resource tokens themselves (small painted rectangular bits) are not marked in any way, nor are the villages on the boards. While I don’t see any easy way to mark the tokens, I think if the villages were marked that would be nice, because each village only contains tokens of its own color, so you could remember which token you picked up most recently.

How to Play P’achakuna

You can download a copy of the rulebook here.

The Goal

The goal of the game is to be the first to own one of each resource by trading with the various villages.

Setup

Assemble the frame (the villages go in rainbow order counterclockwise), and then place the terrain tiles into the frame according to the assembly plan. Place the piles of resource tokens on the corresponding villages. Place all the demand tiles in the cloth bag and randomly draw tiles to place on each village, including the central village. No village should have its own color on its demand tile, and no villages should have white demand tiles during setup—just redraw new tiles if needed, and place the rest back into the bag

Give each player three llamas of their color—one is placed in the central village and is given a white resource; the rest are set aside. The white player goes first. The black player also starts with the extra gray resource, which can be spent by that player but does not count toward winning the game.

Players should sit so that they are each facing a row of the little cutouts on the frame.

Gameplay

On your turn, you may first rotate one terrain tile (any orientation), and you may rotate an additional tile if you spend 2 resources. You may not rotate tiles that are occupied by a llama, and you may not rotate a tile that your opponent rotated on their last turn.

Then, you must move each of your llamas at least one space, unless it is in a village. White llamas may only travel in valleys, and black llamas may only travel on the mountains. (Either color may enter villages.) A llama may travel any distance as long as it stays on its chosen terrain, but it must stop if it enters a village. (Llamas cannot travel on the outside frame—it doesn’t count as valley or mountain.)

After all of your llamas have moved, each llama in a village may trade or buy llamas.

You may sell the resource your llama is carrying, but only if it doesn’t match the village color itself.

- If the resource you’re selling is not on the demand tile, you don’t get anything in return, and the resource is returned to the supply (put it back in the village it came from)

- If the resource is on the bottom half of the demand tile, you put it into your supply.

- If the resource is on the top half of the demand tile, you add it and another resource of the same color (from its village) into your supply.

After you sell a resource, the demand token is discarded and a new one is drawn to replace it—just remember that no village may have its own color on a demand token. (If the bag runs out, put all the discarded tokens back in and mix them up.) Then pick up a resource from the village you’re in and put it on your llama.

If you collect a resource you don’t have yet, you may place it in a cutout in the frame in front of you. (These are still considered as part of your supply and may be spent as usual, but you generally don’t want to.)

To buy a new llama, spend 4 resources, and place the new llama in your current village. Give it a resource from the current village. Each player may have up to 3 llamas total, and on your turn you move each of your llamas independently.

Game End

If you collect one of each color resource, you win immediately.

Why You Should Play P’achakuna

P’achakuna is a pickup-and-delivery game, so a lot of the game is about figuring out the “traveling salesman problem”—what’s the best way to get to each of the different villages to sell your wares? There are, of course, several factors you need to take into account.

First is the terrain. Now, it’s a little odd, thematically, that some llamas can only travel in valleys and others only on mountains, aside from the fact that the terrain is constantly changing on you, too. But it makes for a fun spatial puzzle as you build paths between cities, hopefully without opening up paths for your opponent.

It can be easier said than done. Since the tiles have different mixes of valleys and mountains, sometimes you have a piece that can be rotated almost any direction and it will still connect you where you need to go—but the opposite piece only has a single orientation that will connect you. You’re also restricted because you can’t rotate a tile that somebody is standing on, or one that your opponent has just rotated. But if you walk to the end of your intended path and stop so you can rotate the next tile on your next turn, you might broadcast your intentions, and your opponent could be sure to turn that next tile, blocking you. Of course, if they do that, it means giving up their rotation for their own path.

The other factor, then, is the way that you collect resources: you actually get them when you deliver them. Thematically, this is also a little strange and can make it tricky to remember: when I deliver blue resources to the red village, I get blue resources for my supply, not red. That seems strange—you’d think I would be getting paid in red, but I do get a red resource that I can now deliver. I think of the collected resources sort of like proof of delivery—it shows that I’ve completed a delivery of that color. Your goal, then, isn’t to deliver to each village, but to deliver from each village. That’s a subtle but important distinction, because you do eventually need to visit each village at least once, so that you have the goods to deliver. However, if you make the mistake of delivering the same color to various different villages, it gets you more resources that can be spent, but doesn’t move you toward the victory condition.

If you build paths between some villages, it can be very tempting to bounce around between them, especially if the demand tiles work out in your favor. It feels like quick progress—hey, I can get here in a single turn, and make a delivery already! And then turn back and do it again! But, again, you’re just collecting a lot of the same thing that you have already.

It’s important, then, to continue building out paths in other areas, and allow existing paths to break up if you’ve already delivered those colors. It’s also helpful to keep an eye on what your opponent is working on, because if you can help your path and interfere with theirs in a single rotation, all the better! Another tactic is to beat your opponent to a village that has a demand tile they want to fill: if I know they need to deliver an orange resource, I can go sell whatever I’m carrying at a village with an orange banner. I may not get anything at all, but it clears the banner and I can hope that the next one doesn’t have orange on it.

That’s where the extra llamas come in. If somebody takes out the only banner with your desired color on it, the only way to try for a new demand banner is to sell something somewhere (or just wait while your opponent sells some more), and draw a new banner. If I only have one llama carrying orange, I sell it for nothing, and then have to go back to pick up another orange. Having multiple llamas can be an insurance policy: the first one sells it for nothing, and if I draw an orange demand tile, then next time I’ve already got a second llama on the way.

There can be a bit of luck involved, of course: sometimes you just can’t get the demand tiles you need. Sometimes they just all line up in an order that’s convenient for your paths. Neither player has information that’s hidden from the other so it feels mostly strategic, but the demand tiles add a bit of randomness that can shift the balance at times.

The starting setup is balanced and symmetric with a rotational symmetry: nobody has a clear path to any of the villages, and you have the same field of tiles in three different directions from the center. Because of the tile designs, you can’t just mix up all the tiles and place them randomly, because that could create layouts where it’s impossible for one player to get to a particular village altogether. However, it does make setup a little tedious because you have to get all 54 tiles in the correct places and orientations, and if you decide to play again after you finish a game, it takes a little while to reset.

Despite the setup complaint and some disconnects in the theme and mechanics, I’ve really enjoyed playing P’achakuna. My youngest daughter (7) really took to it right away and requested it many times, both to play the game and just to play with the llama meeples. (It’s handy having extra llamas to play with when you’re waiting for your turn!) Once I showed her how the setup poster works, she would sometimes get the game out and set it up for us to play. My oldest daughter (16) also really enjoyed it, though her busy schedule didn’t allow her as many plays as her little sister.

Overall, I think it’s a nice two-player strategy game, and the dual-layered tiles for building paths are a unique feature. The resource-carrying llama meeples are kind of a gimmick, but an adorable one, and people who like games for their cool components may be as delighted as we were with them. I also appreciate that the publisher Treeceratops—based in Switzerland—has a focus on sustainability, using FSC-certified or recycled materials as much as possible, and limiting their use of plastic. This game will not use a plastic insert, and the small plastic bag for the wooden inserts is unavoidable because that’s how those components are provided to the publisher. If you’re looking for a clever game from a relatively new publisher, check out P’achakuna.

For more information or to make a pledge, visit the P’achakuna Kickstarter page!

Click here to see all our tabletop game reviews.

![]() To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

Disclosure: GeekDad received a prototype of this game for review purposes.