Food is scarce, and the wolves are hungry. Can you lead your pack to dominance and become The Alpha?

What Is The Alpha?

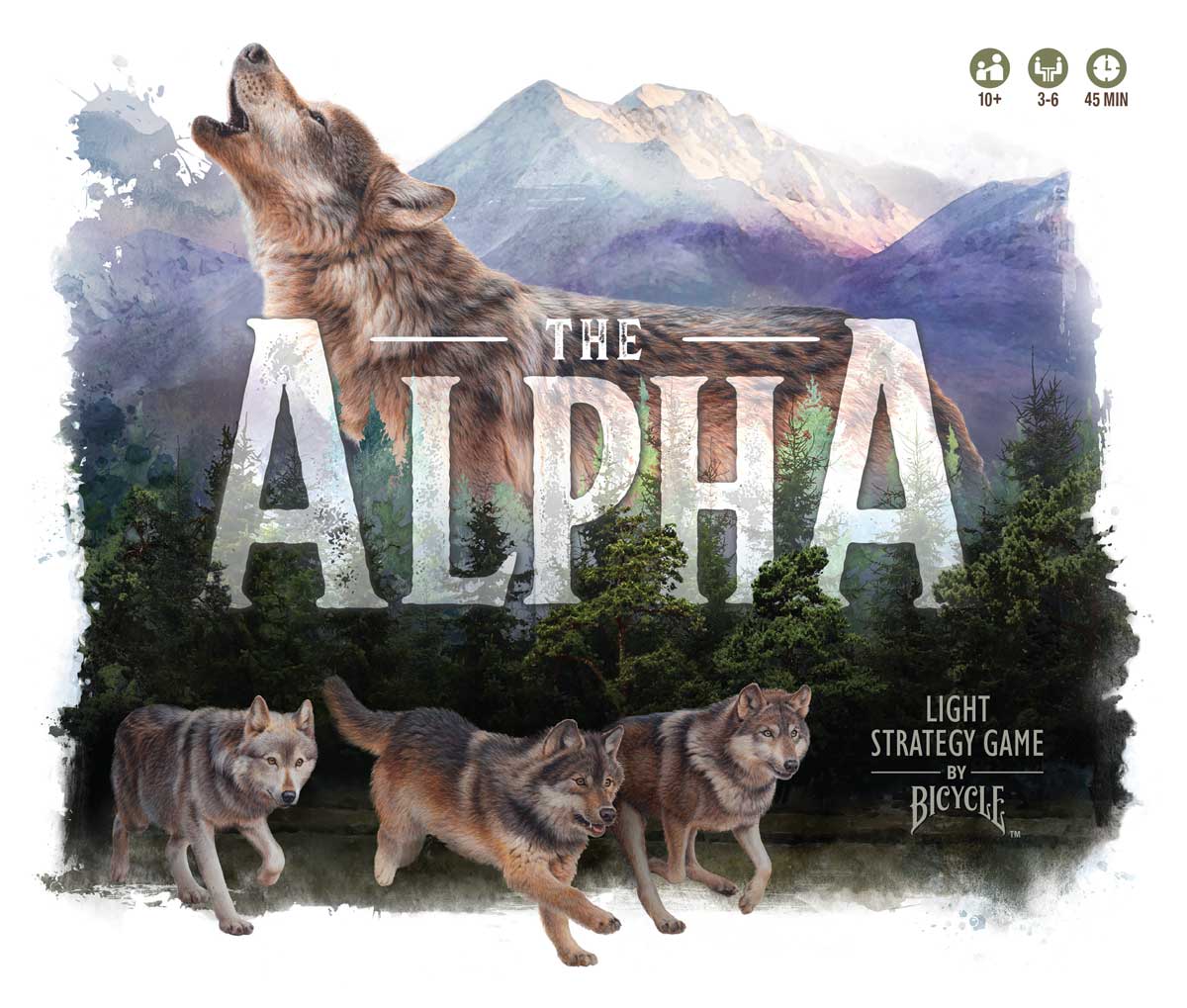

The Alpha is a game about pack hunting for 3 to 6 players, ages 10 and up, and takes about 45 minutes to play. It retails for $29.99 and is available now in game stores, online, and directly from the publisher. The game’s rules are easy enough to learn that I think younger players would be able to play it, though keep in mind that there’s potential for some direct conflict and backstabbing involved.

The Alpha was designed by Ralph Rosario, published by Bicycle, and was illustrated by Andrew Hutchinson.

The Alpha Components

Here’s what comes in the box:

- Food Tracker board

- 6 Den boards

- 11 Region tiles (2 large, 3 medium, 3 small, 2 scavenge, 1 livestock)

- Weeks Left token

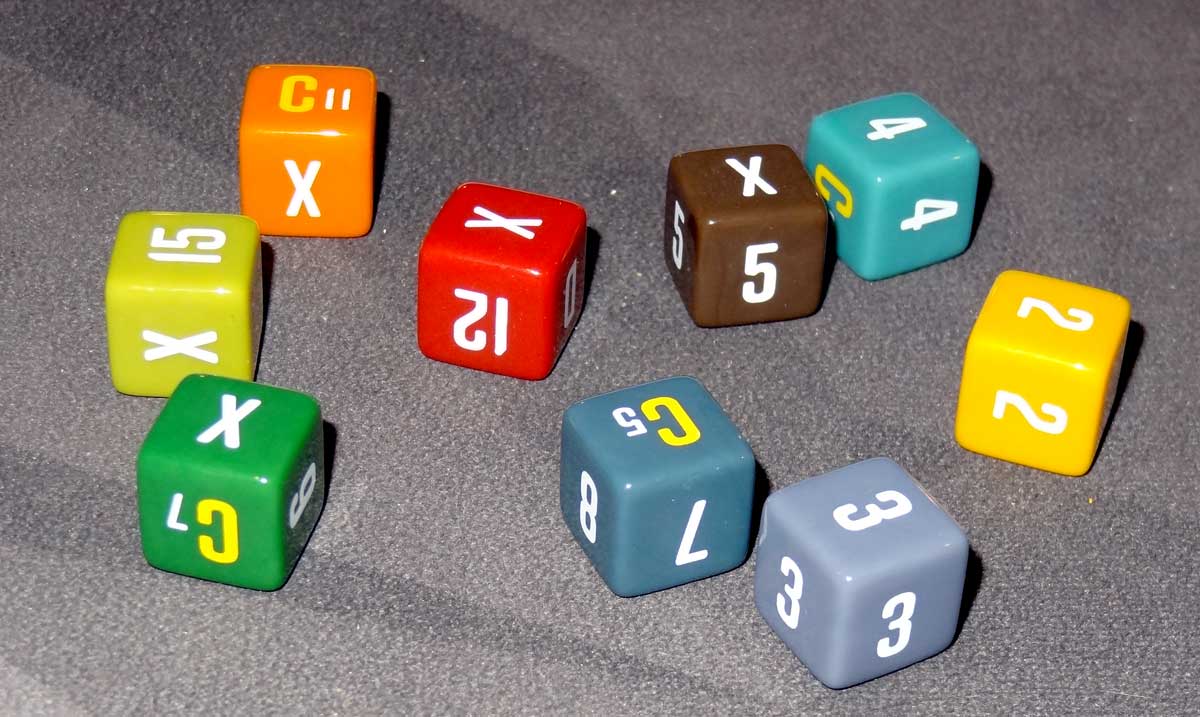

- 9 Region dice

- Alpha token

- Player components in 6 colors:

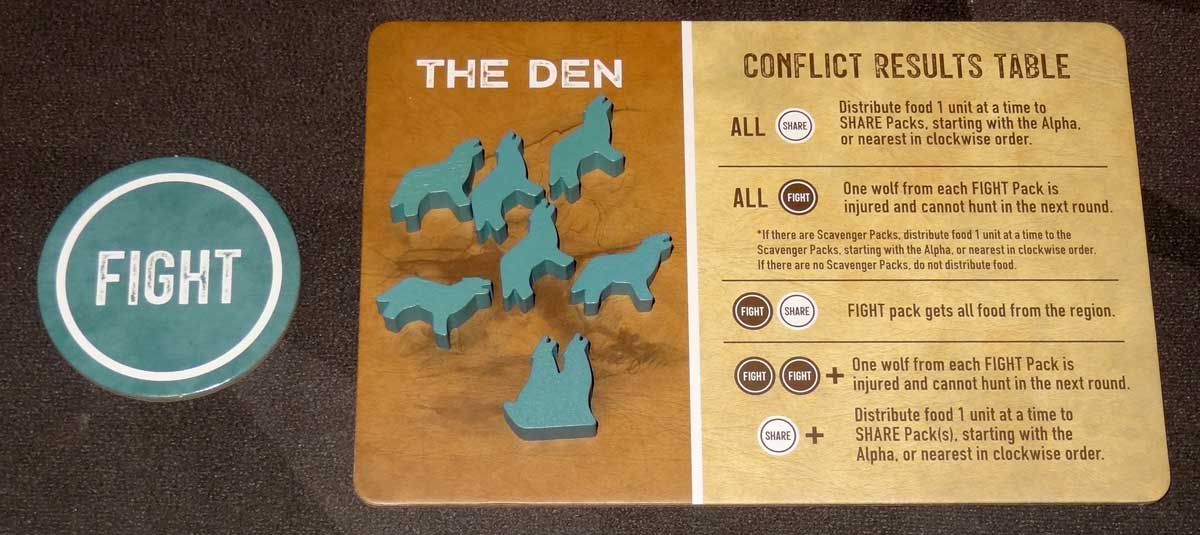

- Conflict token

- Alpha Pair meeple

- 6 Beta Wolf meeple

The components are a nice quality: sturdy cardboard tiles with illustrations of the various animals on the region boards and a forest area on the main food tracker board. The illustrations are are naturalistic and help set the atmosphere of a game set in reality rather than a fantasy world (even if, as I’ll discuss later, the game isn’t strictly scientifically accurate).

The wolf meeples are pretty nice: they’re small, and posed to look like they’re howling. The “alpha pair” meeples are a silhouette of two seated wolves howling—these feel a little less satisfying to me, but it works fine for reminding you that in the game the alpha pair is worth 2 wolves. As you can see from the photo, the colors of the wolves aren’t quite as natural, though understandably so: you need to be able to tell different players apart. But lime green is kind of a bold choice.

The dice are custom six-sided dice, with one corresponding to each of the potential prey that the wolves can hunt. They’re printed, not etched, so I don’t know how durable the numbers will be but for now they show no signs of wearing off. The dice are colored to match the various region boards, and each die’s numerical values are printed on the region board. (Each die also has at least one X face on it, and these are not printed on the region boards.)

The plastic insert has nested wells for the cardboard bits and the dice—the smaller things go underneath, with the large region boards and den boards on top to hold things in place. There are six wells for the wolf meeples, but then there was the odd decision to have the large game board cover up only three of them rather than all six. That means that if you tilt the box while it’s put away, three of the colors will get mixed up with each other. So close!

Overall, the components are pretty nice. Interestingly, this is a strategy game by Bicycle, but it doesn’t have any cards whatsoever in it.

How to Play The Alpha

It doesn’t look like there’s a rulebook online, but I’ll give an overview of the game here—note that I may skip over some of the details, though.

The Goal

The goal of the game is to have the most food by the end of 5 rounds.

Setup

Place the food tracker board in the center of the play area, with the region board nearby—the number and sizes of region boards will depend on the player count. Large and medium boards are placed above the food tracker (in the “deep forest”) and small, livestock, and scavenge boards are placed below (in the “near forest”). Place the corresponding die next to each board. Place the “weeks left” token on the “5” space.

Each player takes a set of wolf meeples and a conflict token in their chosen color, as well as a den board, which also has instructions about resolving conflicts. Place one wolf meeple on the “5” space on the food tracker, and the rest in your den.

Give the alpha token to the player who howls the loudest—they become the first player.

Gameplay

Each round consists of several phases: Stalk, Establish Dominance, Chase, Resolve, and Advance.

Stalk

In turn order, each player places one wolf meeple onto a region tile. If you place a wolf in the deep forest, you must spend a food, moving your wolf backward on the food tracker board.

Continue around the table until everyone has placed all of their wolves. Note that only one wolf may be placed onto the Livestock tile, and only one wolf per player may be placed on each scavenge tile.

Establish Dominance

The player with the most wolves on a tile is dominant for that region. The alpha pair counts as two wolves for dominance. In case of ties, they are all considered dominant. Everyone else who is present in the same region is a scavenger.

Chase

For each region where there are sufficient wolves, the dominant player rolls the die. If there are ties for dominance, the player closest clockwise to the alpha player rolls and looks at the result:

- A number: That’s the amount of food available for the dominant packs.

- X: The prey got away; if there are other dominant packs in that region, they may choose to reroll. Otherwise, the wolves here return to their dens.

- C with a number: The prey was wounded and will become carrion for the next round. All packs (dominant and scavengers) will have a conflict, with the amount of food equal to the number next to the C. Also, flip the tile over to its carrion side—the next round, there is no chase and the food amount is pre-determined.

- D (only on the livestock die): Dead wolf—the rancher got you. Remove your wolf from the game.

Resolve

Resolve all of the region tiles from smallest to largest.

Each pack present on a scavenge tile earns 1 food; wolves return to dens.

If the chase was unsuccessful (an “X” was rolled), wolves return to dens and do not get any food.

Otherwise, if there is only one dominant pack, that pack gets all of the food, and all the wolves return to dens.

If there are multiple dominant packs, then there’s a conflict.

Each dominant pack secretly chooses “fight” or “share” with their conflict token, and then the tokens are revealed simultaneously.

- If all packs share, distribute the food evenly as possible, starting with the player closest to the Alpha going clockwise.

- If only one pack fights, it gets all of the food.

- If multiple packs fight, one wolf per pack is injured and placed in the injured location on the board, and these packs do not receive any food. The non-fighting packs then share the food.

- If all of the dominant packs fight and are injured, then scavenger packs will divide up the food as evenly as possible.

Advance

At the end of the round, move all the wolves from the region tiles and the healing space back to their dens. Move wolves from the injured space to the healing space. Advance the “weeks left” token. Finally, pass the alpha token to the player with the most food. In case of a tie, pass it to the closest player clockwise to the current alpha player.

Game End

The game ends when the “weeks left” token reaches 0. The player with the most food wins and becomes The Alpha. Ties are broken going clockwise from the player with the alpha token.

Why You Should Play The Alpha

There are various things at play in The Alpha, like the trade-off between spending food to go after bigger prey or the risk of losing a wolf when hunting livestock, but the core concept that the game is built around is the prisoner’s dilemma. When there are two players involved in a conflict, it’s closest to the classic prisoner’s dilemma: your best individual result is if you betray the other person but they don’t betray you, but if both people choose to fight then you’re worse off than if you both share. How do you convince the other wolf pack to play nice, so you can bare your teeth and take the whole lot?

But throw in some more wolf packs, and that’s where things get even more interesting. When there are multiple dominant packs involved in the conflict, you want to be the only one who chooses differently. If you fight and everyone else backs down, you get everything. If you share and everyone else fights, you still get everything and everyone else gets injured.

Another twist comes in the payoffs: the smallest of the animals, the hare, awards only 2 food. If there are three packs tied for dominance and all of them share, guess what? The last in turn order gets nothing. On the other hand, the bison can be worth as much as a whopping 20 food, which is certainly enough to share … but that could also set you up for the win if you manage to take the whole thing for yourself.

And, of course, don’t forget about the scavengers! That’s the other thing to figure into your calculations. In the classic prisoner’s dilemma, the two prisoners are the only people involved. Either they go free or they serve a sentence. But in The Alpha, there may be some other people who are affected by your decision, and although they don’t have any say in the matter, they’re definitely hoping that all the dominant packs turn on each other, because then they get to divvy up the spoils.

So, that’s a taste of the various considerations that feed into your decisions about conflicts. How about the placement of your wolves to begin with? Scavenging is a safe bet, but a poor one: everyone can send one wolf per scavenge tile, and there aren’t any conflicts and you’re guaranteed to find food–but it’s only a single food. Wolves don’t subsist on berries alone, you know.

Let’s say you’re going after some real prey. Is it worth it to spend food for the trek into the deep forest? You might spend 3 food to tie for dominance of the deer, and then only get 3 food for your troubles. On the other hand, there’s only so much food to be had in the near forest and there are a lot of hungry wolves to feed.

Going after the big prey can be tough, because you need a minimum number of wolves there: either you go it alone and spend a lot of food to do so, or you try to convince other players to join you. Even then, there’s a prisoner’s dilemma of a different sort. The more packs are tied for dominance, the more chances you’ll have to roll the die for the hunt, which means you’re more likely to bring down the prey and get anything at all. But, of course, then you have to resolve conflicts. If there’s only one dominant pack, then your chances of catching the prey are lower; plus, if you’re too aggressive early on, nobody will join you in the hunt because they know they won’t get anything anyway.

Again, the scavengers come into play. When you see two (or more) players vying for dominance over prey, it can be worth it to put a single wolf onto that region tile. Sure, you’re already outnumbered, but if there’s a tie for dominance, you’ve got a chance at getting a good amount of food for a small investment. All it takes is instigating a fight between the dominant packs!

Finally, you’ve got to consider where (and when!) to place your alpha pair. Place it early and you might stake your claim on a particular animal, daring anyone else to compete with you—if they don’t use an alpha pair as well, you can always stay one step ahead of them. Or, save it for last: other players won’t know for sure if they’ve secured the lead in a region if you still have your alpha pair in reserve.

I mentioned earlier that the game isn’t quite scientifically accurate. Apparently the researcher who popularized the idea of alpha wolves and alpha pairs later acknowledged that he had misinterpreted the data, but it was too late, and the concept had already taken hold. It’s not really a big deal for me, but you may not want to use this as a biology lesson for your kids.

And a note for our current times: The Alpha can work pretty well over video, if you can point a camera down at the board itself (or at least at the various region tiles). The remote players will have to find something to use as a conflict token, whether that’s just a small item they put in their hand for fighting and leave out for sharing, or something along those lines. It can help to send everyone a photo of all the region boards so they know they various food amounts and probabilities of success.

The Alpha, as the box cover says, is a light strategy game. While there are certainly some interesting choices to make throughout the game, it’s not too complicated to learn. You don’t really build up a long-term strategy; instead, it feels like you’re just living from week to week, hoping to be successful in fattening up a bit before winter hits. The dice introduce an element of chance that can heighten the tension: smaller prey tend to be easier to catch than larger prey, though that doesn’t mean I haven’t failed to catch a hare (5 out of 6 chance!) several times in a single game. Because of the prisoner’s dilemma core mechanic, it’s more about reading the other players than it is about figuring out the board.

It works all right at 3 players, but I do think it’s a game where you want as many players as possible, simply because that’s where you’ll get a lot more competition for prey. The excitement in the game comes from conflict, so I think you want as much opportunity for that as possible. It does make the game longer, of course, but I think it’s worth it for the player interactions. I will also note that this is a game where you can win big and lose big. I’ve seen as much as an 18-point difference between the first and last player, and the board itself is only 30 points long. (If you exceed 30, you just tip your wolf over on its side and start again at 1, perhaps indicating that your wolf has eaten so much that it has to lie down.)

If you enjoy light games about playing the other players, and your group doesn’t mind a bit of backstabbing and betrayal, The Alpha might be a good fit for you. However, if you prefer games with a bit more long-term planning, you may want to hunt elsewhere.

Visit the Bicycle website for more information about The Alpha or to order a copy!

Click here to see all our tabletop game reviews.

![]() To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

To subscribe to GeekDad’s tabletop gaming coverage, please copy this link and add it to your RSS reader.

Disclosure: GeekDad received a copy of this game for review purposes.