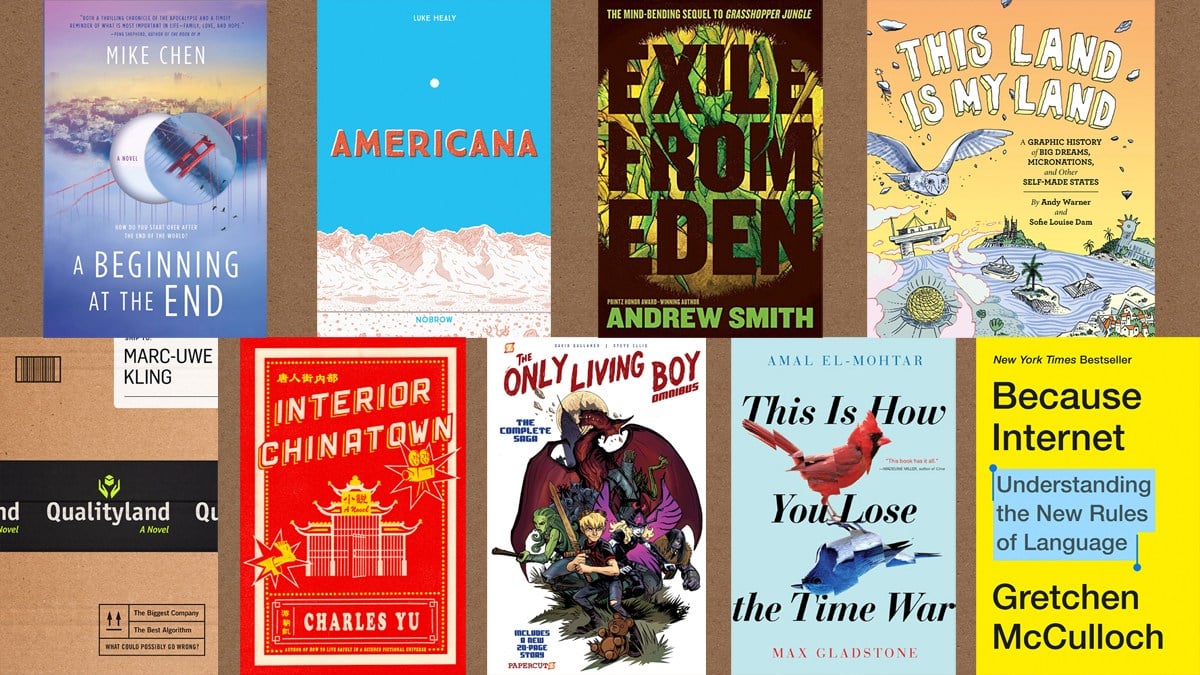

Well, hello there! It’s been a while—I’ve had a hard time getting my engine started back up this year, but I’ve still been reading a lot, with more books to tell you about than I can handle in a single column. This week, I’ll start with some fascinating visions of the world: what it could have been, what it could become, what it looks like from a different angle.

Well, hello there! It’s been a while—I’ve had a hard time getting my engine started back up this year, but I’ve still been reading a lot, with more books to tell you about than I can handle in a single column. This week, I’ll start with some fascinating visions of the world: what it could have been, what it could become, what it looks like from a different angle.

Exile From Eden by Andrew Smith

I mentioned last time that I had started reading Exile From Eden. It’s a sequel to Grasshopper Jungle, a dystopian young adult novel that includes a host of bizarre things, including (from a quote from the beginning of the book):

babies with two heads, insects as big as refrigerators, God, the devil, limbless warriors, rocket ships, sex, diving bells, theft, wars, monsters, internal combustion engines, love, cigarettes, joy, bomb shelters, pizzas, and cruelty.

You can read my original review of it here. Now, I’ll admit that I didn’t go back and re-read Grasshopper Jungle before starting Exile From Eden, but it may have helped to have a refresher. (Note: I’ll have spoilers about the first book here, because it’s hard to describe even the premise of Exile From Eden without giving away the ending of Grasshopper Jungle.)

Austin Szerba made it to an underground shelter (nicknamed “Eden” by the somewhat mad person who built it), along with a handful of other survivors, when the giant mantis soldiers took over the surface. And then he had a kid: Arek, who has only known life inside the Hole, who has never encountered any other humans besides the ones he lives with, and whose understanding of the world before has been pieced together from bits and pieces that his dad brings back from his occasional forays outside. He’s in love with Mel, the girl he grew up with—though of course he’s also not sure of this, because she’s the only girl he’s known other than the adults in the Hole. And when Austin and his best friend Robby leave the hole and don’t return, Arek decides it’s time to go look for his dad, and see what life on the surface is like.

Grasshopper Jungle was about a world falling into ruin and chaos; Exile From Eden is about a world slowly piecing itself back together. Arek soon realizes how little he understands about the world, how unprepared he is, how BIG everything is outside. We also get to meet a mostly naked kid named Breakfast who has somehow survived the giant mantises and has been leaving messages all over the countryside, plus a few other survivors who aren’t always good news.

While the plot of the book—Arek exploring the aboveground world, Breakfast’s travel with his companion Olive—are engrossing and fantastical, a good chunk of the book is also philosophical. Austin tried to raise Arek as a “new human,” one free of the hang-ups and prejudices and arbitrary rules that permeated life Before the Hole, but Arek feels caught in between, often still stuck in old habits and manners. What rules would be in place if we hit “reset” on human civilization? How would life be different? Those are heady topics that you wouldn’t think mesh well with giant murderous insects, but Smith manages to weave them together into a cohesive whole.

Qualityland by Marc-Uwe Kling

Welcome to a world run by algorithms. Everything you do is rated by everyone you interact with, which gives you a rank that determines your path in life. QualityPartner matches you with your best fit; TheShop knows what you want even before you’ve realized it, and has helpfully arranged to have a drone deliver it to you automatically. This amazing country renamed itself—no, rebranded itself as QualityLand, and by law you may only refer to it using superlatives. It’s not a great country—it’s the greatest.

Our protagonist is Peter Jobless (your last name is based on your parent’s occupation when you were born), a low-ranking machine scrapper. It’s his job to crush the various appliances, androids, and other devices that have stopped working because the Consumption Protection Laws have outlawed repairs, but Peter has secretly been harboring faulty machines in his basement. He’s not entirely content in this world but can’t put his finger on it—until the day he gets a product from TheShop that he definitely doesn’t want, and his attempts to return it set off a ridiculous chain of events.

QualityLand reminds me a little of The Warehouse, another book about an Amazon-like business that grows out of control (see this Stack Overflow), except this time it’s less about working for the company and more about being a consumer in that world. The book is heavily satirical and over-the-top, and yet you can see reflections of our current world and the direction we seem to be heading. Aside from customer ratings and ramped-up consumerism, the book also touches on politics (the upcoming election includes a candidate who is an android), Big Data, self-driving cars, and sentient AI.

There’s one character, the Old Man, who seems to be riffing on every movie hacker stereotype—he’s somebody who grew up in our era and seems out of place in QualityLand, but mostly he seems to serve as an info dump for Peter (and the reader), explaining how today’s policies and technology could lead to this dystopian future. That part gets a little heavy-handed at times, but he only shows up a couple times.

Overall, I really enjoyed this book, and I think it pairs well with The Warehouse in its take on corporations running the world. I was a little surprised to find that it was actually written and published in Germany originally, with this English translation by Jamie Searle Romanelli. The scenes with the government didn’t quite feel like it was set in the United States, but much of the rest of the book felt like a satire of my own country. Perhaps a lot of these concerns about Big Data are more universal, and those in Germany are just as affected by ratings and algorithms as we are here.

Americana (And the Act of Getting Over It) by Luke Healy

Americana is an illustrated memoir, partly prose and partly comic book, about an Irish man’s experience hiking the Pacific Crest Trail, the grueling 2,650-mile path that spans from the United States’ border with Mexico to its border with Canada. Healy’s journey, depicted in red and blue ink on white paper, is not just a travelogue about the hike itself, but also a reflection on the idea of America, a dream that Healy had been chasing since he was a child. He had always been obsessed with America, but despite visiting a few times (and coming to Vermont for college until his visa expired), he never managed to stay. As Healy says early on about this hike: “I’m driven by my hunger for the American experience. But also by the hope that if I gorge myself on it, I’ll become sick of the taste.”

The drawings, like the hike itself, are often repetitive, with the not-quite-in-shape Healy huffing and puffing along the trail, sweating in the desert, shivering in the cold, grumbling at his collapsing tent. We get a taste of PCT culture: the trail names that people adopt, the constant evaluation of pack weight, water levels, miles to the next town. Healy’s experience has many bumps along the way: he gets a call from his mom that his grandfather is in the hospital and may not make it, and he’s torn between quitting the hike to head home, or continuing the hike. He’s already made his goodbyes, a tradition each time he leaves Ireland just in case.

Americana is a window into a peculiar world, made all the more so because it’s my world, to a certain extent. Healy is peeking into a subset of American culture from an outside perspective—not only on the trail but in the towns he passes through. What does our country look like to somebody looking in? It’ll make you want to go hike this impossible-sounding trail, and it’ll make you glad that you’re sitting inside on a comfy chair just reading about it.

A Beginning at the End by Mike Chen

This story about the world several years after a global pandemic may feel just a little too real while coronavirus is in the news, but the timing of its publication was coincidental. In the book, a virus wiped out much of the world’s population, and civilization fell apart. Cities were abandoned to gangs of looters, and a decimated government struggled to reinstate basic services in a few major cities, while others have moved into empty cities and created communes.

But this book isn’t so much about the disaster itself or its immediate aftermath; it’s about the people rebuilding their lives or starting new ones. Former pop star MoJo was giving a concert in New York when riots broke out, and she abandoned her controlling father and went on the run, reinventing herself as Moira. Rob survived with his young daughter Sunny, but he never told her that her mother died during the riots, and she still thinks her mother is getting treatment somewhere. Krista is an event planner, helping people continue the traditions of weddings despite the obvious difficulties; she still harbors bitterness toward her family and fights to maintain control of her own destiny.

These characters intersect in San Francisco, one of the cities that is still (somewhat) functioning, and things get complicated. News comes that Moira’s father is still looking for her, offering a hefty reward for information about her whereabouts. Rob is in danger of losing Sunny to the Family Stability Board because of the way she’s been acting up at school, and eventually recruits Krista to help him find “normal” activities to participate in. Krista is planning Moira’s wedding and seems to have it all together, but in reality she’s barely scraping by: if she can’t pay for her residency license, she’ll have to leave the city. And in the meantime, rumors are spreading about another outbreak: will the world survive another pandemic?

I wrote about Mike Chen’s previous book Here and Now and Then last year: it’s a time travel story, but it’s really more about the relationship between a father and his teenage daughter. A Beginning at the End has the pandemic as a launching point, but is again more about some of the specific, quiet struggles of people living in its aftermath. When Rob initially lies to Sunny about her mom, it wasn’t with any sort of plan—she was very young and misunderstood him, and he was relieved to push off the difficult conversation to a later time. But now she’s in school, and her belief that her mom is sick but alive somewhere is leading to conflicts, and Rob realizes that he made a mistake, and continues to make things worse. Now that he’s in danger of losing his daughter entirely, he’s racing to prove himself a normal, caring dad—but he isn’t even sure how.

Moira and Krista are two more examples of strained parent-child relationships. Moira’s father seemed to be interested in her only as a project, shaping her into a pop star and only caring that she gave the right answers at press conferences. He’s framing his search as just wanting to reconnect with his lost daughter, but Moira doesn’t trust his intentions. Krista, meanwhile, grew up with an alcoholic mother and feels like she’s better off without a parent, better off avoiding any close attachments because they just lead to disappointment and pain. When she has the chance to spend time with Sunny, she’s determined to be a better adult than the ones in her own life.

There are parts of the book that felt a little off: Sunny, in particular, acts like a weird mix of ages, like Chen isn’t exactly sure what a 7-year-old is capable of. I know he’s got a young daughter, so perhaps he’s just extrapolating? But she certainly seemed pretty naive in some respects, but then super capable in others.

Overall, though, I enjoyed the book. I like the fact that it’s an End of the World story where life continues after the “end,” and that you get glimpses of what happened six years ago through various formats: excerpts from news reports and websites and books from that period. The descriptions of San Francisco called to mind the scene in Avengers: Endgame where Steve Rogers is sitting with a couple people in a community center for a group therapy session, reflecting that it’s up to them—the survivors—to do something with the world that’s left. Despite the worldwide disaster leading up to the story, it’s ultimately an optimistic view of the world, a hope that it’s still worth building relationships and community even after the apocalypse.

The Only Living Boy Omnibus by David Gallaher and Steve Ellis

Erik Farrell ran away from home and took shelter in a park, but when he woke up the next day, the world had been transformed: the park had become a jungle filled with strange bat-dog creatures, and in the distance he spies a dragon curled around a leaning skyscraper.

That’s how the story starts off, and pretty soon we discover that Erik appears to be, as the title says, the only living boy. He meets an amphibious warrior woman, as well as some sort of butterfly woman. There’s the monstrous Doctor Once, who performs grisly experiments on his captives. And above all of this is Baalikar, the dragon who rules this new world, cobbled together from various dimensions. Erik’s memory is full of gaps, but during his journeys and adventures, bits and pieces return to him, things that he has repressed and tried to forget. As it turns out, his memories are also a key to how he ended up here, though in a surprising way.

This omnibus edition collects the entire saga, originally serialized online, into a single hardcover book. It’s full of adventure, epic battles, and weird monsters, and is quite a romp. Of course, the hero of the story is this random boy who somehow manages to survive and even thrive despite never having had any sort of battle training, and there’s not really much attempt to explain his remarkable abilities, but if you’re already suspending your disbelief for everything else, what’s one more, right?

This Land Is My Land: A Graphic History of Big Dreams, Micronations, and Other Self-Made States by Andy Warner and Sofie Louise Dam

This comic book is an exploration of various attempts throughout history to create new worlds, and it’s pretty amazing. There are communities established by those who wanted to upend social structures, nations that were founded because of strange legal loopholes and contested territories, and (of course) lofty utopian visions that didn’t always pan out the way the dreamers had hoped.

Most of the communities detailed in the book are no longer around, though some physical structures remain. Some are still thriving, and some exist but in very different forms. For instance, did you know that Oneida began its existence as a marriage-free community before it became a silverware company? Did you know that Dean Kamen (inventor of the Segway) has his own island (population: 1), and that he runs for reelection occasionally and always wins?

The list goes on: of the 30 locations included, the only one I had even heard of by name was Oneida, though I didn’t know the story behind it. The rest were new to me, and are astounding. People have built their communities on rafts, in unclaimed territories, and deep underground. Many include elaborate sculptures and buildings that I’d love to see in person.

Each entry in the book is fairly short—just a few pages at most—and I found myself wishing there were more details about them. This Land Is My Land would be a great jumping-off point, though, for anyone wanting to do more research about these curious attempts at self-determination. For anyone who loves reading about weird trivia and strange ideas, this book is your book.

Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu

Longtime GeekDad readers may remember the name Charles Yu: he wrote How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe a decade ago, a book that is still one of my favorite time travel stories. A lot of his fiction is pretty meta—characters who know they’re in a story, for instance—and reading it is a little like watching somebody watching television. So when I heard he had a new book out, I immediately got a copy at the bookstore.

His latest book, Interior Chinatown, shifts from science fiction to something more like a Hollywood story: a guy who just wants to make it as an actor. The main character, Willis Wu, is a bit actor in Black and White, a police procedural show that sounds like every police procedural show you’ve ever seen, the two sexy cops who banter but never kiss, the murder-of-the-week to solve. Willis knows the path: you start off as Background Oriental Male, working your way up to Generic Asian Man Number Three and (if you’re lucky) eventually Number One, with the goal of being Very Special Guest Star. But of course, the ultimate dream, the dream of all the Asian guys who live upstairs from the Golden Palace Restaurant, is to become Kung Fu Guy.

But, of course, things aren’t ever that straightforward when Charles Yu is involved. The book is written almost like a television script, even down to the Courier typeface used throughout, but the TV show and Willis’s real life blend and merge in strange ways. When he’s talking to his father (once Sifu, Kung Fu Master, now Old Asian Man), is he on-screen, playing out a role? Is he having a quick conversation between scenes? Or maybe, somehow, it’s both.

Interior Chinatown is about representation and limitations. It’s about race, and the way that Asians are often left out of the conversation—or excuse themselves from the conversation. Black and White, as you might guess, features a black cop and a white cop, and Chinatown is an exotic setting, full of inscrutable people who have to speak in accented English because that’s what the audience expects. Yu digs into the assumptions we make about each other, and questions the system: what does success look like? Does becoming Kung Fu Guy mean you’ve made it?

I don’t want to give away too much of the plot, but it’s a mind-bendy, thought-provoking read. I really enjoyed it, and look forward to reading it again after I’ve had some time to process it a bit more.

This Is How You Lose the Time War by Amal El-Mohtar and Max Gladstone

I picked this one up at the story because I’m a sucker for time travel books and a friend had recommended it.

It’s a romance story masquerading as a time travel story. In the future, two competing factions struggle for dominance: the Agency is technology and steel; the Garden is organic and genetic. Their agents travel back in time, manipulating events to drive the arc of history toward victory. Red is from the Agency, and Blue is from the Garden. They encounter each other through messages—at the final point in Red’s mission, she finds a letter from Blue, taunting her. Blue has foiled her, slipping in ahead of time and leaving a note instead. Then it’s Red’s turn to add a wrinkle in Blue’s plot, and so it goes.

The book alternates between these letters to each other, and we get glimpses of the world in their descriptions. Some missions seem simple: a person is delayed on the way to work, which sets off a string of events that leads to an important discovery that is no longer discovered. Some require years: becoming part of a community to be in the right place at the right time. The messages become more and more elaborate, not just words written on paper, but seeds that grow plants with leaves in particular patterns that must be decoded, or patterns found in an animal’s fur, or words that appear in flames.

As Red and Blue dance around each other, never quite catching up, they fall in love. They revel in the competition, tell each other what their worlds are like. The story is beautifully written and the worlds that Red and Blue travel through are strange and wonderful, some familiar and some completely new. How can they ever meet, given that they’re on opposite sides of the ultimate war?

If you like sci-fi and romance and a touch of time travel, I highly recommend this one.

Because Internet: Understanding the New Rules of Language by Gretchen McCulloch

I mentioned Because Internet back in October, when I first started reading it, and I continued to dip into it throughout the fall and winter. I’ve always been interested in linguistics and language, and Gretchen McCulloch does a great job of delving into the culture of the internet and how it is shaping language. I’ve always been a bit more of a prescriptivist when it comes to grammar: I want people to follow existing rules, and if we’re going to introduce new rules, I want them to make sense. My position on that has softened a little over the years, though change is still difficult at times.

McCulloch explores how different populations came to the internet, and shows how that can affect how they communicate on the internet—whether they take to email or social media or messaging, for instance. She writes about typography and emojis, memes and gestures. Not only did this book help me make more sense of what I see on the internet, it was fun to read. The book includes serious research, but it’s presented with a light-hearted tone instead of being dry and academic.

Whether you’re a grammar snob like me, or confused about memes, or you love sending all-emoji messages, if you have any interest at all in how we communicate, this book is for you.

My Current Stack

I’ve finally started reading Matt Kindt’s Mind MGMT, a comic book series about a secret government agency that uses mind control techniques. There’s an upcoming board game based on the series (watch for a Kickstarter alert next month!), and I figured it would be fun to see the story it’s based on. I picked up the first collected volume at the store, read it, and went back this week to pick up the other two volumes. It’s another one that would fit well with the theme of this week’s column, but will have to wait until next time.

I didn’t plan ahead for Black History Month with a whole stack of books, but I did just get sent a copy of Me and White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad, and I’m planning to start that soon. I’m expecting it to be somewhat uncomfortable to read, but eye-opening.

In lighter reading, I’ve been reading a kids’ detective trilogy by James Ponti: Framed!, Vanished!, and Trapped! My daughter had read the first one a while ago and said she liked it, and I finally got around to it. I picked up the other two volumes so I could see where else the story goes. It’s a fun story about a kid who uses his “Theory of All Small Things” (or TOAST) to see how small details add up to solutions.

Disclosure: I received review copies of the books listed in this column except Interior Chinatown, This Is How You Lose the Time War, and Because Internet, which I purchased myself.