Do your kids (and you) know how to evaluate information sources—and why it’s important? Here’s a quick primer on media literacy and identifying different types of information.

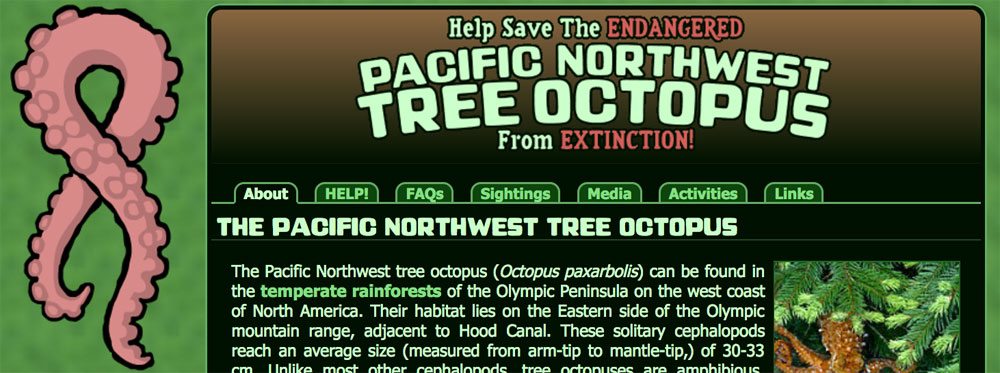

In 1998, Lyle Zapato created a website about the Pacific Northwest tree octopus, an endangered species that was able to live both on land and in water. The site had a section to report sightings of the rare creature, a suggested bibliography for further reading, and suggestions for how to help save the octopus.

But, of course, the catch is that there is no such thing as the Pacific Northwest tree octopus.

Zapato’s site has since been used in media literacy classes, including one well-known test in 2006 in which seventh-graders from across Connecticut were asked to evaluate the website and all of them believed it. Even worse, most of them were unable to find evidence that it was fake even after being told it wasn’t real, and some students even continued to insist that it was real despite being shown evidence to the contrary.

Things have come a long way since then, right? My middle-school daughter has learned about evaluating information sources in her social studies class: they discuss things like why a particular piece was written, who it was written by, and who the target audience was. So how did we end up in a position where we disagree not only on opinions and evaluations of the facts, but on the very facts themselves?

Melissa Zimdars, Assistant Professor of Communications at Merrimack College, has a list of tips for analyzing news sources, as well as a list of sites that have been evaluated. The list went viral in November, and Zimdars wrote a piece for the Washington Post about fake news, where we get information, and even the fact that many people probably shared the list but didn’t actually read it.

Zimdar offers some specific tips for spotting fakes—like “.com.co” domain names that are actually fake versions of legitimate sites—but one jumped out in particular:

If the story makes you REALLY ANGRY it’s probably a good idea to keep reading about the topic via other sources to make sure the story you read wasn’t purposefully trying to make you angry (with potentially misleading or false information) in order to generate shares and ad revenue.

I might edit that to say “If the headline makes you REALLY ANGRY…” because, indeed, more people share links and stories based on the headlines without actually reading the entire story (or, sometimes, any of it). One writer tried to test this theory by writing a clickbait-y headline about a giant asteroid about to hit the earth.

With studies showing that more and more people get their news largely from social media (and Facebook in particular), it has become easier to fall into the trap of the echo chamber, where most of the news you get confirms your existing opinions. We trust links shared by people we trust—our friends—and are suspicious of links shared by those we disagree with. We get angry or excited and it’s so easy to hit that “share” link, figuring that if it’s not true then it’s not going to spread that far anyway, right?

This video shows the contrast between fact-checking and sharing without fact-checking (and, yes, the incident used as an example actually did happen, according to Snopes):

When we read a story online, it’s important to ask ourselves a few questions before sharing or commenting or reacting.

Who wrote it? Is it a known, trustworthy source? Do they cite their sources (and if so, are they report the source accurately)?

Why did they write it? Does the piece look like it’s been written to stir up emotions or to persuade you to believe a particular point of view? Just because something relies on facts doesn’t mean that it wasn’t intended to be persuasive.

And, of course, there’s satire, like The Onion, which is not factual and is not intended to be accepted as fact. The problem is, there are many people who don’t know that it’s satire, and will share links to stories assuming that they’re real. On Facebook, the headline and preview images are much more prominent than the URL, so it can be easy to miss. Plus, there are also newer satirical sites that have cropped up over the past decade that aren’t as well-known as The Onion, so it can be easy to make the same mistake.

If your kids have trouble understanding sources and reliability, try to frame it in ways they’ll understand.

For instance, when my three-year-old told me “nothing happened” when she fell and knocked out her front tooth, I knew I needed to do a little more investigation. She wasn’t a reliable source, and the evidence in front of me (knocked-out tooth, bleeding lip) indicated that something had indeed happened.

Another example of using facts but not describing reality: any time one of my kids tattles on another, but conveniently leaves out her own actions in the conflict. When she says “My sister pushed me!” she may be telling the truth—but she may also be leaving out the fact that she kicked first.

And as far as explaining satire, you may have to draw an analogy to sarcasm or jokes—that’ll be easier for older kids to understand. For younger children, you may have to say that some websites are like joke books for adults.

Of course, there are also instances of fake news: stories that are flat-out false. There are websites—like those .com.co domains—which purport to be one thing but are really another, and include stories that are made up. This is different from just writing a clickbait-y headline on a real story, or conveniently reporting and omitting facts to suit your purposes. It’s particularly important to use tools like Snopes.com or FactCheck.org to check up on a story before believing it. Or, if you don’t like those sites, look up the same story on some contrasting websites, and see how it’s been reported: are there differences in how things are described? Can you find an original source (like a photo or video of a purported incident) to see it for yourself?

Even then, of course, you want to be able to check when a photo is real. Fake or altered photos have been around as long as photography itself, but digital tools like Photoshop make it easier even for amateurs to alter photos. If you look closely at the photo on the right, you might be able to spot evidence that it wasn’t an unaltered image—but if I’d only posted that version on Facebook, you probably wouldn’t be looking for it, either.

There are various ways to check images—the American Press Institute offers some tips and tricks here—and it’s important to remember the ways images can be misused. For instance, you can use a completely real photo but give it a false caption to tell a different story, and images can be cropped to hide “inconvenient” facts. Even video can’t always be trusted: with the minimal cost of shooting videos, it’s possible to edit out hundreds of failed attempts in order to get a clip of several successes, whether you’re shooting hoops or flipping bottles or whatever.

Sharing fake or misleading news can have real consequences. As our kids gain access to social media, it’s crucial that we give them a good foundation to know how to fact-check things before passing it along to their friends.

For further reading, GeekMom Karen Walsh wrote a piece about information literacy in November. Although it’s framed in terms of getting information before the election, her tips and suggestions about fact-checking still stand.

Sadly our trusted friends are a source of fake news. Watch out.

Shiv—I agree, and that’s a good point. Because it’s so easy to share news without even reading it, fake or misleading news spreads quickly among friends. It serves to reinforce our views, and rarely connects or convinces those who disagree with us—who may not be our friends or don’t see our news feeds anyway. It was hard enough back when email hoaxes circulated widely and people often forwarded them without fact-checking—sharing a link is even easier now than back then.

I don’t know how you enforce media literacy—if only you had to have a digital driver’s license before getting on the information superhighway, right?

A very important moral of the story is clear that our trusted friends are a source of fake news. Consequently, fake, disinformation, propaganda, tendentious and incorrect news gets filtered through to children who tend to use their parents mobile handsets. My own experience with WhatsApp messages indicate that most of my friends who forward text and video messages do not read and watch before sharing it with others. This content is relayed which eventually ends up being widely circulated in a multitude of cliquish cicles of friends. This is a disservice to the family as well as to the community. Adults who take things for granted must review their news consumption habit because there is evidence to suggest that social media has increasingly become a source of news and information for many people around the world. Perhaps media literacy courses could be suggested to mobile phone users as a starting point to educate the digital citizenship.

Headlines have always been suspect even back in the days of print newspapers. At least they had editors and fact checkers. Nowadays anything goes as long as it generates ad revenue.

Typos and obvious grammar mistakes at least show there has been little to no review before publishing which could also logically conclude there was little to no fact checking.

One tell tale I have seen often is when a story quotes a website as a source and then the trail goes cold. That website quotes some “authority” with no means for verifying the person quoted is a real person.

Especially suspect if the website source is a copy and paste of another websites’ article or an affiliated website.

A “research study found…x,y, or z is true”, when the source study didnt even ask the question.

Another tell are Advertisments disguised as “product reviews” with nothing but positives and links to where the product is sold.Ive seen ads for marijuana products written as advice on what kind to use for depression, anxiety etc. with no warnings or disclaimers.

I’m glad people like Jonathan Liu are taking time to educate subsequent generations how to navigate the overload of information with practical skills of logic and inquiry. Now we just need the adults to follow suit…

Phil—excellent points. A lot of these are included as flags in Melissa Zimdar’s list, too: that the style and formatting of a website can often give you hints about whether it’s going to be a reliable source. Misleading headlines, using ALL CAPS, poor grammar—all of these generally point to sources that are not just about providing information and have ulterior motives.

That said, GeekDad itself is not a journalistic site. While we do strive to be accurate in what we report and we generally try to be apolitical despite our own leanings, we are a culture/lifestyle blog. We write about things we want to promote, and aren’t here to inform you about everything. So: please keep reading GeekDad, but don’t depend on us for all of your news. 🙂