The German Spiel des Jahres (which translates into Game of the Year) is sometimes called the Oscars of board games. Truth be told: At least with respect to the economic effect, this comparison is quite an understatement. Why? Well, the winners of the Oscars typically already are well-known, the winning movies usually already have generated their share of revenue at the box office. Thus, while winning the Oscars may add a bit to DVD sales and similar, the Oscars will not make or break a movie. In contrast, winning the Spiel des Jahres typically increases sales of a board game by between 100 and 1000 times. So, whereas the Oscars are typically awarded to top sellers, the Spiel des Jahres creates top sellers.

When Spiel des Jahres got started in 1979, I was just the right age to play the winning games: first with my family, later also with my friends. With my kids now in the same age bracket, I find myself revisiting some of my favorites from these early classics.

Classics, indeed, because often, these games introduced game mechanisms that have by now become commonplace. In this post I want to take a look at how two early classics transformed the traditional racing game. I mean the sort of game, in which all players start at one end of the playing field and want to reach the other end; they roll dice to advance, are occasionally helped or hindered by special fields and, maybe some randomly drawn action cards. There are uncountable variations on this theme, quite a few “published” as cut-out on the back of a cereal box or supplement in the middle of a children’s magazine. Probably, most children’s self-invented and crafted games are of this type. Hare & Tortoise and Enchanted Forest took the racing game as starting point, mixed in some other ingredients, and created something entirely new.

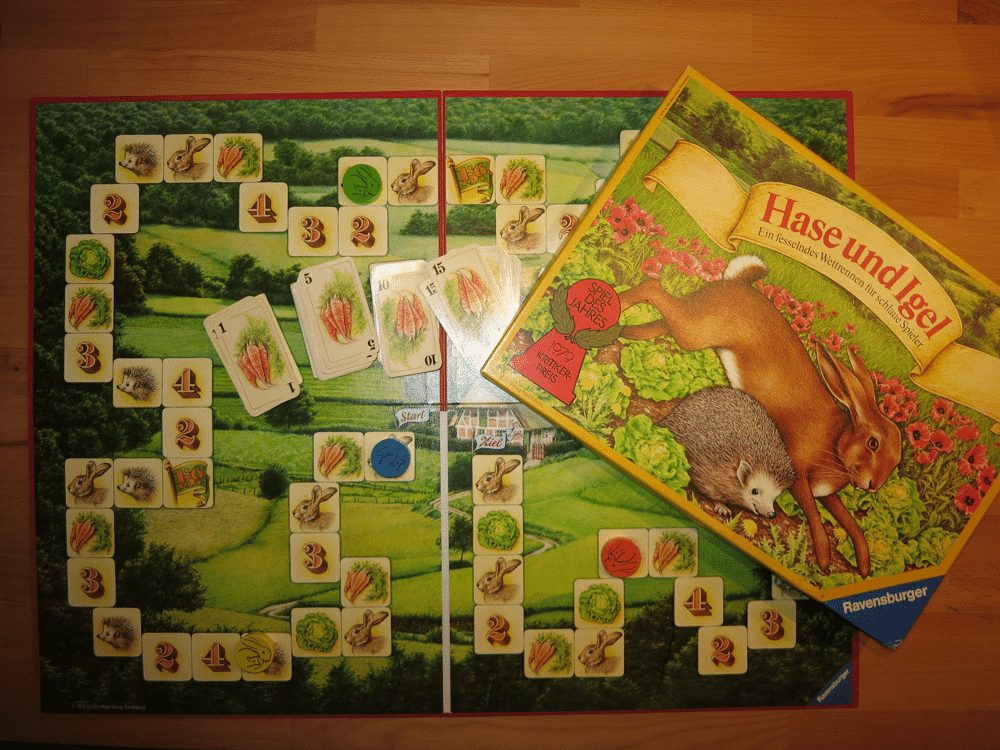

Hare & Tortoise

The very first game to win Spiel des Jahres was Hare & Tortoise by David Parlett in 1979. A racing game, but instead of rolling dice, the players (hares) have carrot cards and can decide for themselves, how far to go in one move. The cost, however, gets considerably higher the further one wants to go in one move: one carrot for the first square, plus two for the second, plus three for the third… and so on. Of course, your carrot cards are limited: You can get new ones either by voluntarily going backwards to the nearest tortoise field and collect 10 carrots per field, by waiting a turn on a carrot field, or – and this is where things get complicated – when moving away from a number field under a certain condition. The condition is as follows: You receive 10 carrots on a field with number one, if you happen to be the first player in the race when it is your turn to move again away from the field. Similarly, the second player gets 20 carrots when moving away from a number two field, and so on. Hares, however, must be careful not to collect to many carrots, the goal may only be passed with at most a certain number of carrots!

All in all (there are a few additional twists not covered in the short description I have given above), these innovations turn Hare & Tortoise into a completely new sort of racing game: Players must manage their resources and need to be careful about their position in the race relative to the other players. How sweet to go back a bit, collecting those precious carrots, while at the same time frustrating the plans of another player to stock up on a certain number field by changing his position in the game!

Because of the level of strategic thinking that is required (and the ability to sum up carrots – a table that translates number of squares into carrot cost is provided, but the player still needs to count how many carrots he actually has in his hands), your kids should be at least eight years to have fun with Hare & Tortoise. To get a better impression of the game, you can look at the complete rules of Hare & Tortoise published on the author’s website.

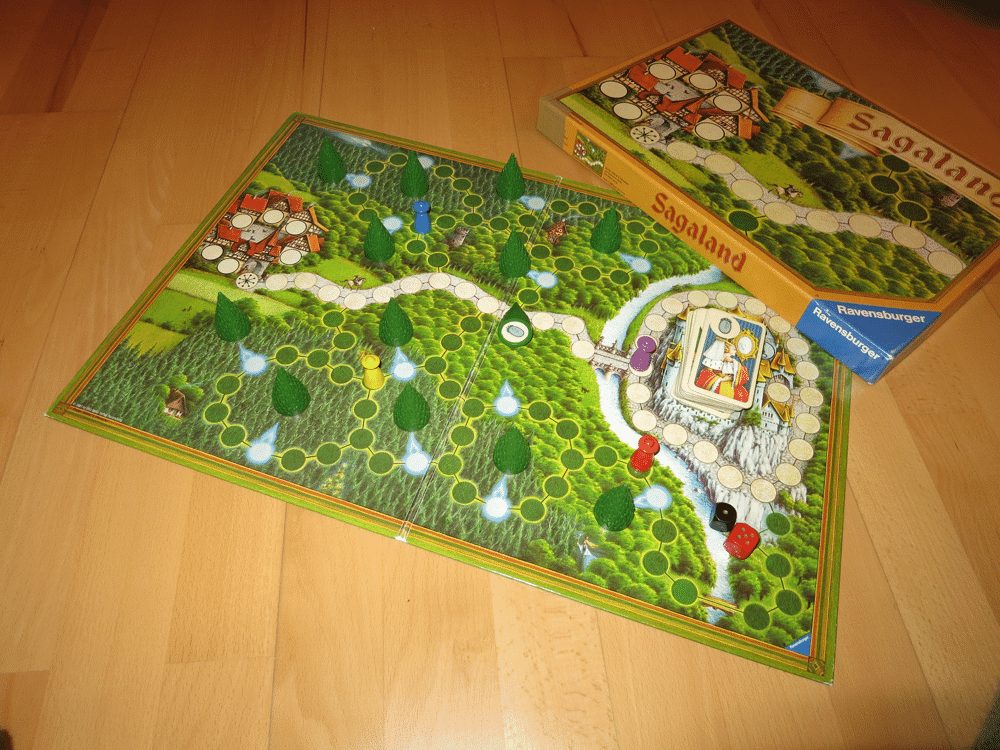

Enchanted Forest

The winner of 1982 (after prices going to Rummycub in 1980 and to Focus in 1981) presented a quite different take on the racing game: Enchanted Forest by Alex Randolph and Michel Matschoss combines the all-time classic Memory with racing. The players start in a village and eventually want to reach the castle, where the king will ask them about the location of various famous fairytale objects: the frog king’s golden ball, the boots of Puss in Boots, the shoe of Cinderella, etc. In order to win, a player must reach the castle and in total answer three of the king’s questions correctly. At any time, the current question is represented by the top-most card on a stack of cards located in the castle. An incorrect answer will throw the player back into the village; for a correct answer, the player receives the top-most card, thus uncovering the next question of the king.

On the way to the castle, the players have to cross the enchanted forest. They should take some time and explore this forest, because said objects are hidden under its trees: Stop at a tree, lift it, take a peek and remember what you saw. But careful: When another player arrives at the location one is currently occupying, back to the village it is!

Thus, both memorization a la Memory and, again, strategy enter this racing game. Should I run to the castle as soon as I know about the location of the object displayed on the top-most card? Or should I try to discover a few more objects, and start the race as soon as a second player has discovered the object in question? When I am in the castle and the king asks me for an object I do not know the location of: Should I guess and risk a journey back to the village, or should I leave the castle on my own accord and return to the forest?

Enchanted Forest (in German: Sagaland) is one of my all-time favourites – unfortunately, my family does not love it quite as much, because, if I may say so, I am so fiendishly good at it. My kids have yet to realize that an alert player may be able to draw essential information from offhand comments such as “I have seen that somewhere, but don’t remember now” or “I have never seen that object before”. I watch their moves and know which trees they have already examined and which they have not. I watch their faces and usually notice, when they have just found the object of the king’s desire (the usual mad dash towards the castle right after looking under that particular tree is, of course, also a giveaway.) Sherlock Holmes would have loved Enchanted Forest!

You can play Enchanted Forest with children as young as five years old. You may have to help them a bit with making their move, though: Every turn, each player rolls two dice and then makes two moves – on for each die (the complete rules for Enchanted Forest are available online). Thus, the young ones usually require help in combining their moves such that they manage to visit as many trees as possible. But if you refrain from using each and every trick in your book, also the five-year olds will enjoy playing Enchanted Forest.