70 years ago today, on August 6, 1945, an American B-29 Superfortress bomber known as the Enola Gay took off from the island of Tinian in the Pacific Ocean and, accompanied by two other aircraft, flew about six hours to the city of Hiroshima in southern Japan. Her cargo was a single bomb, Little Boy. At 8:15 in the morning local time, Little Boy was released. It fell for approximately 43 seconds before detonating about 600 meters over the city, and which point it exploded with a force equivalent to 16 kilotons on TNT.

While the atomic age can more accurately be said to have begun several weeks earlier with the first-ever atomic detonation, it is the bombing of Hiroshima, and subsequent bombing three days later of the city of Nagasaki, that made the bombs’ existence public and truly ushered in the atomic era.

The blast instantly killed an estimated 60,000 to 80,000 people, almost all of them civilians. Another 40,000 or more were killed instantly in Nagasaki. Within months, those numbers would rise into the hundreds of thousands as the Japanese people became the first in the world to suffer the effects of radiation poisoning en masse. The total death toll from both bombings is unknown, but the memorials in the two cities list the names of over 450,000 believed killed.

The bombings were justified by the US as a way to bring the war to an end quickly. Without question, the losses that would have resulted from an invasion of the islands by ground forces would have been far greater, and on both sides. But there are many accounts that say that the Japanese, their military forces already on the brink of collapse and their cities already suffering from withering Allied bombings, were preparing to surrender, and that the Soviet declaration of war on August 8 played a far bigger role in their decision to give up than the atomic bombs. As with so many other historical events, we can’t ever truly know, and whether or not there might have been a better way is something that historians will likely continue to debate for all time.

What there can be no doubt about, though, is that by dropping the bombs the US declared to the world that we had in fact solved the riddle of the atom. The bombings were in many ways less the final shots fired in World War II as much as they were the opening salvo in the Cold War. Just slightly over four years later, on August 29, 1949, the Soviets would test their first bomb, and the nuclear arms race was off and running. We need look no further than the current debate over the Iran nuclear deal to know that the ripple effects of those months in the summer 70 years ago are still being felt today.

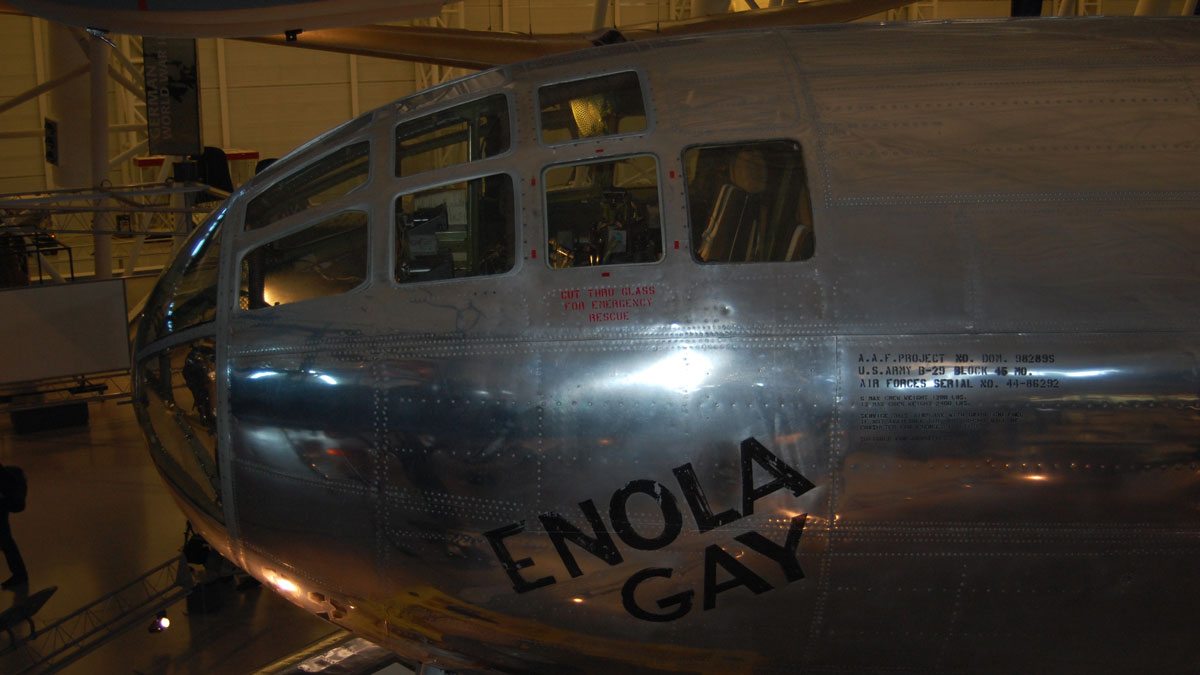

Visitors to Washington, D.C. can see the Enola Gay on display at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles International Airport, part of the National Air and Space Museum. Bockscar, the B-29 that dropped the bomb on Nagasaki, is on permanent display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force in Dayton, Ohio. In Hiroshima itself, the Prefectural Industry Promotion Building, one of the few buildings to survive the blast and now known as the A-Bomb Dome, stands as a lasting peace memorial.

The last surviving member of Enola Gay’s crew, Theodore Van Kirk, died on July 28, 2014 at the age of 93. The last survivor of the Bockscar crew, Frederick Ashworth, died in 2005. One man, Lieutenant Jacob Beser, had the distinction of flying on both atomic missions. He died in 1992.

Many survivors from both cities are still alive, most of who were just children at the time of the bombings. Many of them, and many others from both sides, have devoted their lives to ensuring that August 6, 1945 and August 9, 1945 go down in history as the only days in human history on which nuclear weapons were used in war. Whether you believe that the US was right to use the bomb or not, I suspect that is something upon which we can all indeed agree.

Note: the title of this article is from a British newsreel detailing the bombing.

Here’s more history I learned while living in Japan. The Japanese maintain a list of names of the dead (they call ‘hibakusha’). But they only allow Japanese names in it. Koreans and others who were also killed are not recorded. While many Japanese say that they are for peace, they don’t demonstrate this by recognizing that others suffered in the war, this is true in Hiroshima as elsewhere in the country. To read a Japanese history textbook one can only wonder at the extent of the Japanese delusions about the war.