Pete Docter and Jonas Rivera, the Director and Producer of Pixar’s Inside Out, met with members of the press at the Beverly Hilton on Sunday, June 7 to talk about the making of the film.

Docter explained the inspiration for the film, saying, “I noticed my daughter growing up, being a little less goofy and wacky and funny and a little more shy and quiet because she had turned 11. And at the same time, I was looking at different ideas for a film and thought about emotions as characters.”

He pitched the film first to Jonas Rivera, and later to Pixar head John Lasseter, asking “What if we have an 11-year-old girl who’s moved across the country, but she’s actually not the main character; she’s the setting, because inside her head are her emotions that help her deal with everyday life?”

At that point, the project was just that concept. Lasseter initially couldn’t conceptualize the premise, Docter explained, but “he said later, ‘This is such a cool idea. It’s got a lot of complexity and a lot of potential. It’s also gonna be really hard,’ and I didn’t really see that at the time. I was too taken by the fun of it.”

Rivera elaborated, saying “I remember when we first did our first pitch-slash-screening to the rest of the group there, the brain trust. I remember it was Brad Bird, he said, ‘This is a great idea. I’m glad you guys are doing it.’ It was a tough nut to crack.”

One of the themes that Inside Out touches on is growing up and saying goodbye to your childhood, a theme that shows up in a lot of Pixar films. Docter and Rivera agreed that it is a recurring theme, but it isn’t something they talk about. “We talk about it through the work,” said Docter. “Have you ever read Peter Pan? I just was reading it to the kids, and it is so poignant and so moving. It’s something that we’re taken by, for sure.”

Rivera added “I’m a parent now. My kids are nine and seven and three, so they’re younger. And I guess I’ve always been drawn to those stories, and it just feels like that is common at Pixar. Maybe it’s because we actually act like we’re ten-year-olds all the time. I don’t know what it is. But Pixar does feel a little bit like this Neverland we’ve built and that it’s – I don’t know – maybe we’re the Lost Boys or something.”

“I think the other thing that affects us is we’re trying to put our own life experiences up on the screen,” Docter explained. “I don’t think there’s been anything that has impacted me near as strongly as having been a parent. And so that experience just continues to inspire and challenge and move us in ways that everybody can resonate with.”

The decision to include only five emotions as the film’s characters grew out of the research Pixar is famous for. “The very beginning pitch, I think I had pitched optimism, which is, we learned later, not really an emotion, and joy,” said Docter. “So I had fear and anger and some other ones, and we realized, man, we don’t really know anything about this. So we did a lot of research, and that’s where this came from.”

“There is no consensus amongst scientists about how many emotions there actually are. Some say three; some say 27; most are somewhere in the middle. So we realized, well, we get to kind of make this up. So we arrived at five, mainly because it’s a nice odd number. It felt like a good crowd, enough contrast and conflict between them, but not so big that you’re, like, ‘Wait, who’s that again? Schadenfreude? Okay. Lost track of…’ We ended up at these five, largely because of the work of Dr. Paul Ekman, who was one of the consultants on the show. And he had originally, back in the ’70s, posited six. It was our five, plus surprise. And we felt surprise, as a cartoon, is probably fairly similar to fear. So we jettisoned that one, and that’s how we ended up with the five.”

Docter and Rivera discussed casting the actors to play the five emotions. “A lot of the lines on paper, if you read the script, they’re, like, sort of funny,” Docter explained, “but just when these particular actors bring them to life, it’s somehow so specific and so wonderful that it’s fantastic.”

Anger

Anger

Docter: Lewis Black was one that, even as I was pitching the concept, I would say, “Imagine the fun we’re gonna have when it comes to casting. We could get people like Lewis Black as Anger,” and people would go, “Oh, yeah, I get that.” So, when we cast him, Jonas called him.

Rivera: Yeah, I called Lewis through our casting department at Pixar, and we pitched him the movie. We wanted him to play Anger. And he immediately, like, I think what he said was, like, “Great, real stretch casting, guys, brilliant.”

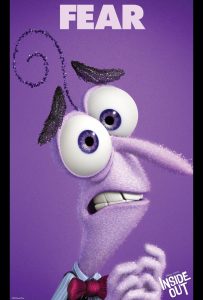

Fear

Fear

Rivera: Bill came on pretty early. I was just a fan of Bill Hader since Saturday Night Live. And it turned out Bill was a fan of Pixar. We didn’t know it. He shows up one day at Pixar, and our casting director calls, says, ‘Bill Hader’s in the atrium. Does anyone wanna go have coffee with him?’ So we go down there, and there’s Bill Hader drinking coffee by himself. And he had, on his own dime, flown up, just because he loves animation, and he loves it. I mean, Bill knows more about movies than anyone I’ve ever known, animated or otherwise. And we just fell in love with him. He came on to write with us actually because he’s such a great writer, and he was so much fun in the story room. And we just went through the script, and he started developing voices, and he kind of leaned towards Fear, and he was kind of perfect at it. He really brought this sort of, I don’t know, Don Knotts, sheriff of Mayberry, like, quick turn on a dime that made us laugh, and he fit.

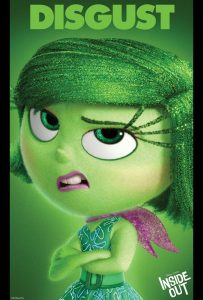

Disgust

Disgust

Docter: Disgust, we struggled with a lot, because we weren’t sure whether she should be disgusting or disgusted. And once we arrived at disgusted, Mindy’s voice came up. And she, again, takes lines that are, like, fine writing and makes them amazing to listen to. And she, like most of the cast, we would come with the script and I would say, ‘Do you have any other ideas for this? Go ahead and play around.’ And she would come up with little alternate lines and asides and added a ton to both the character and the film.

Sadness

Sadness

Docter: Sadness was one that, early on, we actually had that character as male in the very first versions. And then, as the film went on, we realized we have too many guys in this movie, especially if it’s taking place in a girl’s head. And I think that was about the same time when you had found Phyllis Smith.

Rivera: I saw her in the movie, Bad Teacher, and she was just so funny. I think hesitant was what – because you had written her more like a crybaby.

Docter: Yeah, she was showing up crying all the time.

Rivera: Always crying, which was funny, but in Bad Teacher, she was hesitant and couldn’t even order a chicken sandwich. Like, ‘I’ll have the chicken sandwich?’ Everything had a question mark, and that felt right, and it worked. And that’s how we ended up playing the character, and she just nailed it.

Joy

Joy

Docter: Joy was the last one to be cast, and it was the most difficult of any of the characters to write for because she had a tendency of being really annoying. If you write someone who is always chipper and upbeat and, ‘Come on, guys, we can do this,’ it just kind of got like, oh, you wanna sock that person. And so Amy was able to put that in some way that made it just entertaining. It was not insufferable. You root for her.

Once she joined the cast, Amy Poehler became an asset not only as a voice actor, but as a writer. Docter described the first day of recording with her, saying “I don’t remember whose idea this was, but instead of recording right away, we spent the whole day reading through the script, one sequence at a time. And then Amy would start narrowing in on certain lines, not just for her, but some of the other characters, as well. And so she’s got such a brilliant writing mind, as well as being an amazing performer. We took advantage of that.”

In the film, Riley’s emotions are a mix of both male and female characters, while her mom’s are all female and Dad’s are all male. Docter explained that this was done primarily for clarity of storytelling. “When we tried it with a mix of male and female and moms and dads, it just got confusing,” he said. “So you’re cutting from 4 locations, 18 characters, and you’re, like, ‘Where am I again?’ So we just went for the obvious of all dads have mustaches; all moms have the glasses and the hair, so you instantly know where you are. And that just made it work a lot better.”

Developing the look of the characters and their color schemes was “kind of fun,” Rivera said, “because it was such an abstract process. Pete had said he wanted these characters to look like our emotions feel, which was hard for the art department to then chase down what that would be. We didn’t want them to be little people or little Muppets. What are they? Albert Lozano, our character art director, came up with this great little simple drawing of shapes, and I thought it was really cool. It was just each one of them as a different shape.”

“So Joy was a star, and she was literally this golden, illuminated, almost like a sparkler, like an explosion. Even her body language, she’s always out. And Sadness was a teardrop, so even the shape and color and her hair, sort of almost a waterfall. Fear was just a raw nerve. He drew this straight line, like he is tight and conservative, and he’s wound up. Anger’s a brick, this immovable briquette or something that could blow his top. He just was a square. And Disgust was a stalk of broccoli. He just drew that like our kids would be disgusted by that. And that was just this metaphoric way to attack them all, and they sort of retained that shape and color as they went on, I mean, purple really not so much, I guess.”

“I remember having discussions about, obviously, you say, ‘I feel blue,’ so some of them were a little more obvious, in terms of colors,” Docter added. “Other ones, like you were saying, purple for fear just kind of – we chose purple because it was left over. It was a good color that kind of rounds out the cast, not so much that purple evokes fear, I think.”

“But we were joking, like, we hope someday, that’s the grammar. Like, ‘I’m so afraid, I’m purple,’ like that will stick somehow,” Rivera replied.

At one point, Joy and Sadness pass through the Abstract Thought area of the mind, and are gradually reduced to deconstructed simple shapes. Docter commented, “it was one of those that, as soon as we came up with that concept, I was, like, we have to do abstract thought. And it was one of the early sequences that, even as the rest of the film didn’t work, even John was, like, ‘That was gold.’ So what it does for us is just take advantage of what animation can do, really pushing the visuals, and it fit. As we did the research, we found out abstraction is something that is a little more advanced thinking. It’s usually age six or seven when kids are slowly able to conceive concepts that are not physical objects in front of them. So we figured that’s a more recent development in Riley’s brain. Bing Bong [Riley’s long-neglected imaginary friend, voiced by Richard Kind] doesn’t really know what it does because he’s like a three-year-old.”

Inside Out shows the emotions working at a control console that looks a bit like the bridge of the Enterprise on Star Trek; Docter explained how this concept developed. “From the very beginning, we thought of the emotions as being some sort of controls because I feel like that’s probably how they would work, right, in other to affect us emotionally.”

“We didn’t want it to be too science fiction, Rivera added. “And you can imagine, in this movie, without any visuals, reading it, it did sort of lean that way. So we worked really hard to make it whimsical and fun, like the mind of a little girl.”

“And, of course, then once we had that grammar,” he continued, “then you could be, like, Dad’s as more of a NORAD computer, you know, old-school coffee cups on it. You could kind of echo that. And there’s just, we hope, just enough logic in the buttons and the way it would work that you would just buy that it was – and when we get too literal, it would almost feel robotic, like they were driving. I remember even looking at the Millennium Falcon. You just buy that there’s a throttle. You kind of don’t need to know more than that. I’ve always sort of accepted those buttons worked and did things. And we kind of wanted the similar grammar, but in a fun way. It was almost like this combination of It’s a Small World and an Apple store. It was whimsical and whirligigs and same with the console. But it was also serious. It was just clinical enough to work and be functional and so forth.”

Another inspiration for the film was the Cranium Command attraction at Disney’s EPCOT Center. Rivera acknowledged that, saying “we’re huge fans of the park. 45 minutes after [Docter] pitched this movie, I’m, like, we gotta call the guy – we’ve got to get a ride at Epcot. This has got to go back to Epcot. So, yeah, we’ve been on that and loved that.”

“I actually animated on that when I was at Disney in ’89,” Docter replied, “and at the beginning, there’s a pre-show with all the heads. So I did a lot of the Xerox, and my head was in it, so that was kind of cool. But I think it actually showcases kind of the difference between the approach. It was like they were talking to the stomach and the heart and the liver and different things. In this one, we said, let’s just differentiate from the body and make it the mind. And so that allowed us a whole different playground.”

Although Joy is the central character, it was important to the filmmakers to give each of the other emotions their due. “That was fairly central to the whole theme of the film, Docter stated. “I think, from the beginning, we felt like, okay, Joy has a character who’s rootable. We all want to be happy. We want our children to be happy. Yet, life is not always like that. It’s full of disappointments and loss and difficulty. And so that’s really where all the other emotions come in.”

“We sort of knew that we wanted to talk about that from the beginning. But it took us a long time of finding just the right specifics to be able to dramatize it, even pairing Joy with Sadness. She was initially paired with Fear for quite a long time during the story development process, but Fear didn’t really provide Joy the message she needed to know. At the end of the film, we wanted her to go back and do something that she could have never done at the beginning of the film, based on what she’d learned. And Sadness, which at first seems like something to avoid – it’s negative; we don’t want it to be part of our lives – you come to realize that’s actually an essential part of dealing with loss, right? It slows you down. It allows for recovery. It even exhibits signs to other people that you need help. And that really was, to me, the central theme of this film; coming together and finding the most important thing, relationships with our family, with our friends. And Sadness, though she seems negative, is really central to that community.”

When asked for an update on Toy Story 4, Docter and Rivera were succinct:

Rivera: Toy Story 4?

Docter: No.

Rivera: I was gonna say there are toys in it.