While I enjoy playing (and DMing) Dungeons & Dragons, I have an even bigger interest in the history and rules development of my favorite RPG (and so many others). I find many games extremely interesting in both the playing AND the study of their rules, and this fascination is strongest with the early days of D&D and its close family members. For me, D&D’s siblings are Metamorphosis Alpha, Top Secret, Gamma World, Boot Hill, and Star Frontiers. I’ve played each and every one of them at some point in time, and when it comes to their rules and style of play, they are all enjoyable to examine.

But it’s D&D’s parent that I wish to spend some time examining here, and that game is Chainmail, written by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren. Chainmail is widely recognized as the rulebook that Dave Arneson used as inspiration and foundation for his Blackmoor campaign. It’s this ongoing campaign (and a demonstration witnessed by Gygax) that grabbed Gary’s attention and spurred him to work with Arneson to begin developing the rules that would become Dungeons & Dragons.

Note: I’ve summarized in the above paragraph just the tiniest of fragments of the story. I love the history of Chainmail and D&D, but my stronger interest is in their rules. For a more definitive history of both games’, you’ll want to read Playing at the World by Jon Peterson.

Chainmail isn’t the complete title of the rulebook; that would be Chainmail: Rules for Medieval Miniatures. From the title, you should first gather that this is not a traditional war-themed boardgame. The two keywords here are “medieval” and “miniatures.” Chainmail was released as a set of rules for simulating battles fought during a recognizable period of time — the Middle Ages — complete with knights and archers and catapults and much more. The rules also provide for using tiny figures (often made of lead) in the shapes of various types of soldiers. Taken as a whole, Chainmail was a sourcebook for conducting games of battle using miniatures, scenery, and weapons of a medieval flavor. Chainmail also contained a section on extending the basic rules to allow for fantasy-based battles, complete with dragons, goblins, and wizards. But that’s jumping ahead a bit, and a short examination of the basic Chainmail rules (minus the fantasy-related elements) offers up some nods to a handful of rules that D&D players might recognize.

Note: I’m using my own 3rd edition copy of Chainmail as source for rule references. There were some differences between editions, but these were mostly related to additional monsters and spells for wizards and a change of “hobbits” to “halflings” to remove a copyright conflict with J.R.R. Tolkien’s estate.

For the 45-page rulebook, the actual rules don’t begin until page 8; the first few pages are dedicated to a brief description of wargaming, the equipment and tools (such as a sand table that is useful for creating terrain and allowing multiple players easy access to their miniatures), and some examples of how a game is conducted. While the overview is nice, the Chainmail rulebook’s introduction doesn’t appear to be written for a complete novice; some of the terminology and discussion clearly expects a certain familiarity with wargaming in general — the discussion on a point system for “buying” troops and the mention of “morale” checks and victory conditions all hint at a certain expectation by Gygax and Perrin that the reader have at least a passing knowledge of the basics of table wargaming. This is going to become more apparent once a dive into the rules is begun.

When speaking of the rules, I need to clarify that the book is actually broken into three different sections when outlining these rules. There’s a section for miniature combat when miniatures are being used to represent larger forces. In the opening section of the rules, a specific ratio of 1:20 is provided — one miniature equals 20 game units whether they be archers, light infantry, or other combatants. Another section relates to 1:1 combat — man to man. And finally, a section provides rules in a section titled “Fantasy supplement” that I’ve already briefly mentioned above. (The fantasy rules build on the foundations provided in the previous sections and are not stand-alone rules that can be used while ignoring the other sections of Chainmail.)

I’m going to begin with the basic miniature combat rules related to non-1:1 ratios. I’m not going to go deep into every rule section provided in Chainmail. Instead, I’m going to point out what I believe are some interesting aspects of the combat rules and point out sections that may be of interest to modern-day D&D players.

Miniature 1:20 Rules (Mob Combat)

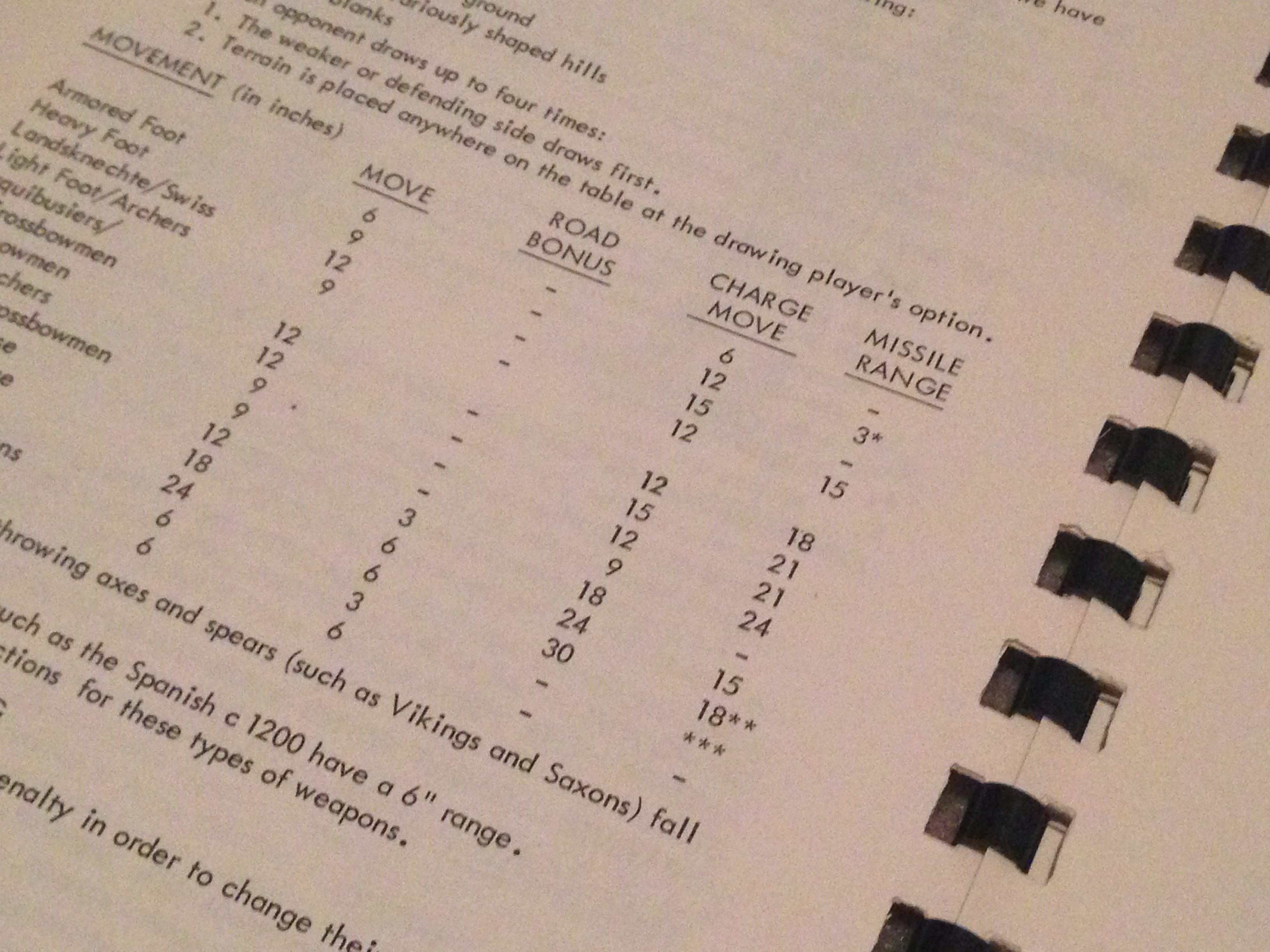

The rules begin by recommending a miniature size — 40mm — and defining that ratio of 1:20 — one miniature will equal 20 game units. The suggested scale is also given as 1″ = 10 yards (30 feet). Compare that to today’s 5e D&D rules, where miniatures used are of the 25-35mm variety and typically represent a 1:1 ratio on a 1″ = 5′ (feet) scale.

Right away (on page 8), there are some details that stand out and differ from today’s D&D combat. With Chainmail, there were two different movement and combat systems that could be used — (1) Move/Counter Move System and (2) Simultaneous Movement System. In a nutshell, the Move/Counter Move method used a simple die roll to determine which player moved first. Just like rolling Initiative, the higher the roll the better. With the Simultaneous method, players would right down the “orders” for their army — these included movement directions, firing orders, and conditional orders (such as “if the archers retreat, charge with cavalry”). Players would take turns performing “one-half moves” that would result in incremental movements of all forces on the table, resolving any combat needed (such as when two miniatures crossed paths) before another set of movement orders were executed on the table. I have no idea which combat system was more popular, but I think you’ll agree that both systems likely resulted in very lengthy games where large numbers of miniatures were involved.

Note: I saw a table-based war game played many decades ago. I don’t recall that it was a Chainmail rules game, but I do remember watching for maybe 20-30 minutes and realizing that the three or four armies (there were more than two players) had all moved maybe twice. Lots of rulers were pulled out for measuring distances, and everyone seemed to have a large binder containing the rules that they were constantly referencing. I remember two players getting into frequent debates over tiny details of the rules. The slow speed of the game was definitely noticeable and likely the reason I never sought out an opportunity to play. (That and the high cost of all those miniatures that my young self had no chance of ever affording.)

For pages 8-24, key rule sections are written in caps and underlined. No chapters here. And while there does appear to be some bit of logic for the order in which the key rule sections appear, some sections can branch off into lengthy sub-sections of rules (that use a header with underlined mixed case — an example: MISSILE FIRE is a key rule section, while a few of the eight sub-sections include Rate of Fire, Split-Move and Fire, and Cover.

As you read over the various key rule sections (and sub-sections), one thing becomes very clear — to play using the Chainmail rules definitely requires a level of record keeping that would make many (or most) modern-day gamers shake their heads in disbelief. I know you want some examples, so consider these observations:

* Fatigue — moving your men around on the table causes fatigue. There are four different situations that players must monitor that can bring on the penalties of fatigue — (1) Moving a miniature for five consecutive turns, (2) Moving a miniature two consecutive turns, charging, then meleeing, (3) moving one turn, charging, and then meleeing two rounds, and finally (4) meleeing three rounds. Consider that players might have a dozens or even hundreds of miniatures on a table that would each need to be tracked for just the Fatigue rule. And when a miniature is fatigued, there are three penalties that must be tracked for that miniature (and the units it represents) – (1) They attack at the next lower unit level, (2) the units defend at the next lower value, and (3) morale for that group drops -1 for other situations to be resolved.

* Rate of Fire — When it comes to firing rate, Archers, Crossbowmen, and Longbowmen are all treated the same and may fire every turn. BUT… only Archers and Longbowmen who do NOT move and are NOT meleed at the end of a turn may fire twice. BUT if Crossbowman, Archers, and Longbowmen are moved up to one-half their normal movement distance (EXCLUDING charging), they may fire once. BUT… if they are moved over one-half normal distance, they may fire once ONLY if their combat roll beats the opponent’s roll. Got it? Oh, and Heavy Crossbowmen fire every other turn. I haven’t even cover rules for horsemen with bows, horsemen without bows, stationery missile troops, multiple ranks (rows) of archers, and axe and javelin throwers (who fire once per turn BUT can always fire at charging troops).

* Modern day D&D players may find it interesting that so many Chainmail players (and other miniature game players) would often bring a number of “tools” to the game — I’ve already mentioned rulers, but there are more. With Chainmail, a catapult’s damage area was determined by placing a pre-cut “circular plastic disc” (two different diameters are given for Light catapult and Heavy catapult) to determine the Hit Area. And cannon fire rules describe using a wooden dowel along with a segmented piece of paper that tracked variations such as “irregular gun barrels and windage.” Seriously.

When I DM a combat scenario with my players, at most I’m tracking maybe five or six variables on my side — HP, AC, movement speed, and maybe some spells for spell casting creatures among others. These Chainmail players probably hauled in reams of blank paper with which to track fatigue, rate of fire, and dozens more details related to their armies. That snap you just heard? That’s my salute to these game players who had some amazingly complex and lengthy rules to track and honor.

When I DM a combat scenario with my players, at most I’m tracking maybe five or six variables on my side — HP, AC, movement speed, and maybe some spells for spell casting creatures among others. These Chainmail players probably hauled in reams of blank paper with which to track fatigue, rate of fire, and dozens more details related to their armies. That snap you just heard? That’s my salute to these game players who had some amazingly complex and lengthy rules to track and honor.

Frequently, the Chainmail rulebook will have ONLY one or two sentences for a sub-section rule. Nevertheless, it’s a rule that would have to have been known by all players in order to maintain fairness. Here’s an example:

Missile Troops: Missile Troops interspaced with other footmen forming a defensive line may “refuse” combat and move back 3″ out of melee range. However, if the other footmen who are melee are killed or driven away, the missile troops must fight if the attacker is able to continue his charge move.

There are dozens and dozens of similar complex statements scattered throughout the rulebook. And these are just the text-based rules. Throughout the rulebook, there are dozens of charts and tables to be used. Want to know if a group of Swiss Pikemen will remain on the battlefield after their ranks are reduced to 50% or less? Roll two d6 and hope for a 5 or better. Not bad odds. But did your Heavy Foot soldiers just lose 1/3 of their number? Roll two d6 and hope for a score of 7 or higher or those soldiers are “removed from play immediately unless no route of retreat is open to it.”

And speaking of retreat, there is a surprisingly detailed two-page set of rules related to every post-melee fight and morale. Every. Single. Melee. Encounter. In a nutshell, both players determine who lost the least and the most and the (positive) difference is calculated. A d6 is rolled and the value is multiple to this difference. Perform the same calculation for the side with the greater number of surviving troops (just those involved in the melee). Consult a charge to find another multiplier that is based on the troop type (peasant, heavy foot, other?). Compare scores using a percentile table that includes notes such as (1) “0-19 difference — melee continues” and (2) “60-79 difference — retreat 1 move.” Morale is a significant game mechanic in Chainmail, and has a number of charts related to it that include the taking of prisoners, retreat conditions, and more.

Later in the basic rules section, there are a number of optional rules for “added realism.” I particularly enjoy the table for determining the action taken by mercenary troops prior to any turn begins. Roll a d6 — a 1 gets you “More pay! Stand, no attacking or movement” and a 2 gets a commander “March off board (things aren’t going well at home, they say). Don’t roll a 3 — “Bribed! March to join the enemy (as soon s they reach the enemy lines they turn and may attack you).” A roll of 4-6 and you’re safe for three moves… no rolls needed. Other optional rules cover weather, baggage/supply encounters, and even special features of an army commander.

Note: Page 20 provides a list of specific fighter types from different countries and time periods — Mongols, Russians, Scots Infantry, and even a table that explains whether Chinese, Korean, and Japanese armies possessed certain types of units. (Korea and China both lacked Armored Foot soldiers and Longbowmen… who knew?)

There’s a closing section in the 1:20 rules that covers sieges that is well worth a read — so many great little rule details that cover the use of towers, gates, ramparts, cannons, catapults and even boiling oil. For war gamers wanting a castle siege, the Chainmail rules were substantial enough to guarantee hours (but probably actually days) of gaming opportunities. (It should be noted that the siege rules apply to the equipment and structures — the 1:1 rules covered below were to be used for “small battles and castle sieges.”)

I hope I’ve been able to give you a glimpse of the complexity that Chainmail rules brought to mob combat. Keep in mind that these army-based rules (not the 1:1 rules) are spread out over almost two dozen pages — I’ve made mention of only maybe half a dozen paragraphs of rule details.

Before moving to the 1:1 rules, I thought it would be worthwhile to examine the current 5e D&D to see what rules are available in terms of managing large combat situations (mob combat). I can’t speak for other DMs, but there is an upper-limit for me when it comes to managing a combat scenario. When it comes to creatures, anything more than a player/monster ratio of 1:5 is just too much. Assuming I have six players, tracking movement, hit points, special abilities, and such for 30 attacking creatures becomes extremely time-consuming. From my point-of-view (the DM), it really slows down the pacing of an adventure. And I imagine from a player’s point of view, waiting for 35 other actions to occur (5 players + 30 players) before being able to take another action is also frustrating and probably quite boring.

On page 250 of the 5e Dungeon Master’s Guide, there is a short section (“Handling Mobs”) on managing combat for large groups of monsters. In a nutshell, the DM simply determines the minimum To Hit by subtracting it’s To Hit modifier (such as a +2 bite attack) from the target’s AC. A small table is consulted and provides the DM with the minimum number of attackers needed (for seven different D20 possibilities – 1-5, 6-12, 13-14, 15-16, 17-18, 19, and 20). If the d20 value needed to hit is 15, for example, the minimum number of creatures needed for a hit is 4. So, if 16 kobolds are attacking, four of the sixteen will hit automatically.

I’ve used kobolds as the examine creature, but the wording of the rules indicates that the group of attacking creatures do not need to all be the same type. Even better (for the DM, worse for the player) is that the rules specify that the creature(s) that do the most damage will be selected in the group of successful hits AND if they have multiple attacks, ALL attacks are successful and damage can be calculated separately. Ouch. (When the number of surviving creatures is reduced to a small enough amount, it is suggested that combat change back to individual attacks.)

Note: DMs can find a potentially useful version of this type of combat modified to handle saving throws here. Be sure to check out the comments as one commenter provided another mob combat option involving breaking creatures into units of six.

With 5e D&D, you can see that mob combat is handled in a much simpler manner than Chainmail, but don’t ignore the fact that Chainmail’s complexity was intended from the beginning. War game fans WANTED realism, and to obtain sufficient levels of realism meant adding rule upon rule as new situations were discovered during game play. Chainmail’s rules weren’t written overnight — they developed both from previous war-game play (by Perren and Gygax, obviously) and most likely plenty of play testing prior to the rulebook’s release.

Compared to Chainmail, D&D players do give up a lot of realism when it comes to combat, but that is balanced with faster combat resolution. Of course, there’s also the role-playing element offered by D&D that is lacking (for the most part, except for possibly roleplaying the general of an army) in Chainmail. First and foremost, Chainmail was a war gamer’s game, not an RPGer’s. Different rules, different expectations. But Chainmail’s mob combat rules did move us one step closer to Dungeons & Dragons. Another step would be taken with the next rules section of the rulebook.

1:1 Miniature Combat Rules

The 1:1 rules begin on page 25 and continue to page 27, the shortest of all three sections in the Chainmail rulebook. For these three pages of rules, however, one page is dedicated to Jousting rules (non-combat) and references a chart in the back of the rulebook that I’ll cover shortly.

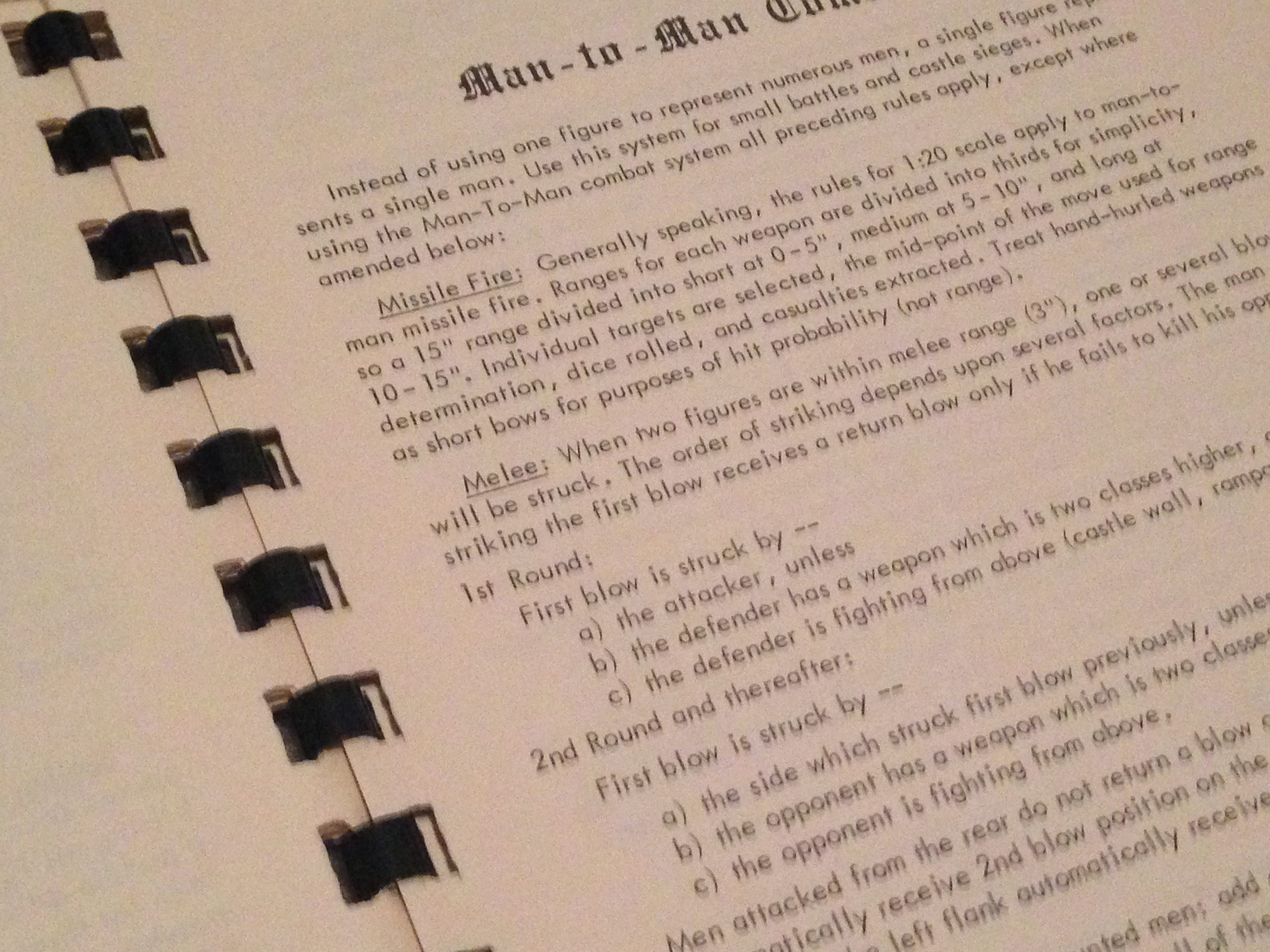

The Man-to-Man Combat rules states that “all preceding rules apply, except where amended” and for two pages, only a handful of the 1:20 Chainmail rules are superseded. Most of the changes relate to the order of combat (here, there is definitely a first attacker instead of the simultaneous combat) and if this attacker manages to kill the defender, the defender does NOT attempt a return attack. There are also some rule clarifications related to flank attacks and mounted-versus-non-mounted combat.

One section of the rules might be of interest to D&D players — how weapons are ranked when it comes to attacks and parrying. There’s a chart at the rear of the book that ranks weapons by a “class” number — a simple dagger is ranked 1 (along with a hand axe), a sword gets a value of 4, a spear 8, and a pike 12. There are 13 weapons in all that are given a class value. The class value is used to quickly determine whether a defender could parry an attack — if the defender weapon’s class value is lower than the attacker weapon’s class value, a parry could be made. Simple, huh? There are more specific rules — “For any weapon 1 class higher to three classes lower than the attacker the defender may parry the blow by subtracting 2 from the attacker’s roll, but he has no counter blow.” (Remember, this is Chainmail — more rules meant more realism.)

Note: It’s also interesting that the number of attacks per turn was also defined by the class of weapon used. If a class difference between attacker and defender was 4, the defender would get two strikes per round. A difference of 8 would allow the defender to strike three times per round!

One final bit of ruling that I found interesting occurs just before the Jousting rules — it mentions a type of soldier called “Viking Berserkers.” Berserkers didn’t wear armor, but were treated as if they had leather and shield. They took a -2 on attack rolls, but would charge automatically upon seeing troops in a battle and would fight to the death.

As for the Jousting rules, the interesting part is how useful these could be in a modern-day D&D campaign. The rules use 2d6 and rely on both players selecting (in secret) an Aiming Point (attack) and Position in Saddle (defense). The chart at the back of the book is consulted, aims are compared to where each player is sitting and an outcome is generated that could include loss of helmet, knocked from horse, a miss, or an injury. Interestingly, the point system subtracts points if a player injures the other player. How chivalric!

With the 1:1 section of rules, players were provided with a barebones set of instructions for conducting combat on a more “personal” scale. Although the rules didn’t provide any assistance in “fleshing out” a role with a name, rank, or other personal information, it’s not hard to imagine that some Chainmail players may have created records for their jousters or other combatants. Even if that wasn’t the case, the rulebook was about to provide another set of rules that would come to be used by Dave Arneson and his players who WOULD begin to track their successes and failures using persistent combatants.

With the 1:1 section of rules, players were provided with a barebones set of instructions for conducting combat on a more “personal” scale. Although the rules didn’t provide any assistance in “fleshing out” a role with a name, rank, or other personal information, it’s not hard to imagine that some Chainmail players may have created records for their jousters or other combatants. Even if that wasn’t the case, the rulebook was about to provide another set of rules that would come to be used by Dave Arneson and his players who WOULD begin to track their successes and failures using persistent combatants.

The Fantasy Supplement

And now we arrive at what (at the time) was one very controversial section. According to Playing at the World (by Jon Peterson), the decision to include fantasy-based rules for combat didn’t have the blessing of every war game player. But my goal here isn’t to address whether the rules should or should not have been included — if they hadn’t, it may have been years or more before a game like Dungeons & Dragons made its way out into the world.

Note: Without Chainmail and the Fantasy Supplement, it’s unlikely we wouldn’t have had a fantasy RPG of some sort. Jon Peterson has a must-read over on his blog concerning a fantasy RPG that was being slowly-but-surely developed concurrently as D&D. It’s difficult to determine from the article whether this other game relied on knowledge of Chainmail and the Fantasy Supplement, but it is comforting to know that even if D&D hadn’t been developed, something would have filled the void.

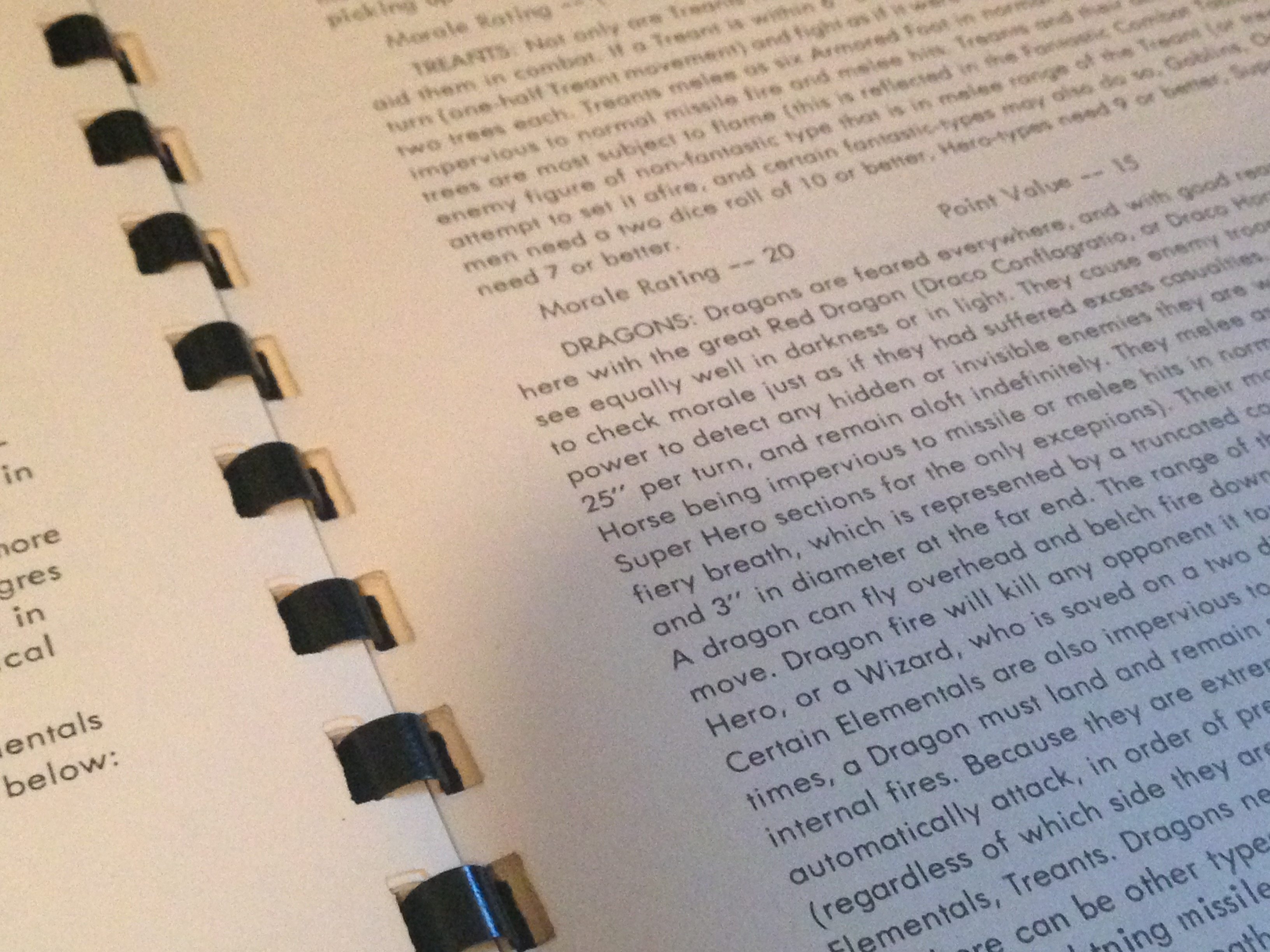

The Fantasy Supplement still focused on miniature combat, but in this case it allowed for non-human combatants — hobbits, dwarves, gnomes, goblins, kobolds, orcs, trolls, giants, and yes… dragons. These creatures (along with human combatants) all had point values, and players could command small or large mixed armies by simply deciding on a maximum point value and then “buying” their army prior to battle. As with Chainmail, these combatants also came with a Morale Rating value that would allow for use of the basic 1:20 and 1:1 Chainmail rules.

Almost all of the non-human combatants came with a one or two paragraph description that provided extra rules for their use. Orcs, for example, came from five different tribes, and while they could be used in individual units, if two units of orcs from different tribes came within a specific distance, they would attack each other! Definitely a good idea to keep your orc units a safe distance apart, right?

Included with the “creatures” were two interesting types of combatants — Heroes and Super Heroes. (And there was an anti-hero type as well.) Heroes were bigger, badder fighters… and could take on multiple units instead of one-on-one — it takes four normal hits from standard troops to kill them (versus one). They don’t have morale checks, and they always die last in a grouping. Super-heroes required eight normal attacks to kill them! And get this — a super-hero could kill a dragon with a bow and arrow by rolling two d6 and rolling an 8 or higher (7 or higher with an enchanted bow). Don’t we all wish D&D dragons fell so easily.

In addition to traditional “fighter” types, the Fantasy Supplement also contained rules for Wizards. Unlike D&D, Wizards could use magical weapons and had the ability to become invisible on the battle field until they attacked. They could affect morale (friendly or opponent), and were impervious to normal missiles (arrows) but had to roll 2d6 and score a 7 or higher to survive a magical missile attack from an enemy wizard. Their two basic attacks included Fire ball (two words) and Lightning Bolt, although they had other spells they could use. A lightning bolt was instant death to any combatant other than giants, hero-types, and a few other opponents, but even those hardy types required a sort-of saving roll with 2d6.

Note: Some observations and corrections from Jon Peterson (thanks, Jon!): “Wizard magic account also reflects 3rd ed Chainmail not 1st. Only 8 spells in 1st, 16 in 3rd. Counterspell not in 1st. No PFE, Haste, etc.” and “Other 3rd vs. 1st: no magic armor in 1st, or Levitate spell. In counterspell, weaker wizard needs 9 or higher, not 8.”

When dealing with wizard-vs-wizard spell combat, all wizards had a “counter spell” they could cast to defend against any spells cast their way — the more powerful wizard would roll a 7 or higher (2d6) and the other (weaker) wizard’s spell fizzled. (The weaker wizard required an 8 or higher for the counter-spell to work.) The sixteen other spells available included Phantasmal Forces (created another combat unit for four turns), Darkness, Wizard Light, Detection (for detecting concealed and invisible enemies), Protection from Evil, Haste, Polymorph, and Anti-Magic Shell (my favorite) that created a bubble-like force field over a a unit and prevented no magical attacks for six turns.

Note: As with D&D, a wizard could only cast a spell while stationary and “undisturbed.” This is similar to the Concentration rules for today’s D&D.

Different levels of wizards could be purchased for varying points — more powerful wizards would gain the ability to cast a higher number of spells and a great range for their damage/effects. Of course, buying an exceedingly powerful wizard meant an immediate bulls-eye for that unit. There was an optional Spell Complexity chart that required a player to roll a value based on the type of wizard ( the lowly Magician, Warlock, Sorcerer, and super-powerful Wizard), and the spell level (1 to 6). After a spell was cast and the roll made, there were three possible spell effects — Immediate, Deferred (one turn), or Negated (failed).

While other types of dragons are mentioned briefly the rules only cover the “great Red Dragon (Draco Conflagratio, or Drago Horribilis)” and its special abilities. Flying, detecting invisible creatures, automatic morale checks for certain distances, and, of course, a deadly blast of fire. After using its breath, though, the dragon must land and rest for one turn. The rules even provided for a specific hierarchy of attack — dragons would attack giants before trolls, for example.

Note: The rules do mention blue, black, white and green dragons (Chlorine breath!) but it’s interesting that a specific one is mentioned as being flightless — the purple dragon (also called Mottle Dragon) fights with a venom tail attack.

The Fantasy Supplement begins to close things down with a few pages covering magical weapons (only two are mentioned — magic arrows and magic swords), magic armor, air movement and combat (wizards could fly using the Levitate spell), and the first mention of “multi-class” considerations — Moorcock’s Elric is mentioned specifically as a Hero who casts spells and who wields a magic sword. The concern with this option is that it might destroy “play balance.”

The final bit of rules in the Fantasy Supplement are related to a familiar topic to D&D players – alignment. With Original D&D (OD&D), there were three options for choosing a combatant’s general lean towards good or evil — LAW, NEUTRAL or CHAOS. These three choices made a direct jump to what would become the first set of D&D rules! (NEUTRAL was renamed Neutrality in OD&D, but eventually changed back to Neutral.)

With just twelve pages making up the Fantasy Supplement, it’s simply amazing to consider that today’s 300+ page D&D manuals began as a sort-of “Some of you might like this kind of thing” addition to the basic medieval combat rules provided in Chainmail.

Conclusion

If you’re a D&D fan, you have three key individuals to thank. Gary Gygax is the name most frequently given as the creator, but I always try to give credit to the other two — Jeff Perren and Dave Arneson. First, Jeff Perren is the co-author of Chainmail. I think it’s safe to say that without Chainmail, Dave Arneson might never have developed his Blackmoor campaign that caught Gary Gygax’s attention. No Chainmail, no Blackmoor… no Dungeons & Dragons. Maybe Gary Gygax would have developed something like D&D at some point, but it’s hard to argue that the Fantasy Supplement portion of Chainmail along with the rules of miniature combat didn’t give Dave Arneson and his players a solid foundation for what would become the first dungeon romps.

I have a lot of gaming history stacked or lined up on my bookshelves, much of it wearing the badges of wear and tear that all good gaming reference materials do. Among those items is my copy of Chainmail. It’s thin. It has a plastic ring-bound spine. It’s silver cover lacks any colorful graphics. It’s got misspellings. It’s a book that in today’s world might easily be passed over on a gaming shelf with its self-published look and feel. But I wouldn’t trade it for a shiny copy of every 4th edition D&D hardcover ever released. (Translation: a LOT of books.) This is, for all practical purposes, a historical document. This is an early piece of gaming history that I want to pass on to my sons if/when they catch the D&D bug. (And when they’re older. MUCH older.)

I’ve enjoyed thumbing through the rulebook again and examining its pages and its rules. If you’re unfamiliar with Chainmail… now you are not. I hope you enjoyed learning about the rulebook, but I can promise you that nothing compares to reading the entire 45-pages. It can be a bit mind-numbing, I’ll admit… but it’s also a chance to take a look at the plumbing and wiring of an old ship before it gets refitted. What you’ll see are numerous instances of old rules, creatures, and charts that have morphed and evolved to become part of the D&D that we love to play today.

Thank you, Jeff Perren. Thank you, Dave Arneson. And, last but not least, thank you, Gary Gygax.

—–

UPDATE: Unearthed Arcana: When Armies Clash

As I was putting this post together, the folks at Wizards of the Coast released a timely update for the Unearthed Arcana series of blog posts. Unearthed Arcana are a set of posts that provide new game mechanics that are considered experimental and possibly unbalanced if used in a campaign. On March 2, 2015, a new 9-page document was made available for managing large mob combat titled “Unearthed Arcana: When Armies Clash” that provides a very interesting read for DMs and players who might wish to invite a large-scale castle siege or army-vs-army combat scenario that won’t take days or weeks to complete. You can download the PDF document here. Below is an examination of a few of the document’s combat rules.

This is an interesting document — there are so many nods to Chainmail, intentional or not. The rules do provide a different set of terminology, however, and I see many more differences than similarities. That said, the Unearthed Arcana: When Armies Clash rules manage to provide in nine pages what Chainmail did in 20-30 pages. Let’s take a quick look.

* Combatants are broken into two types — Stands and Solos. Stands are groups of identical creatures, ten per group. They fight as a single entity and must be Huge size or smaller. Solos are for larger creatures or players (or NPCs controlled by the DM). For time and scale, a combat round is now 60 seconds long and instead of 5′ squares each grid represents 20′. There’s also some very specific rules when it comes to moving diagonally as diagonally contiguous squares (touching at a corner) are not considered adjacent when moving groups.

* Stats such as AC, HP, and special attack and defense abilities are all the same for a Stand, and speed is calculated by dividing a creature’s normal movement (such as 30 feet) by 5. And stands can be grouped together in Units that have their own sub-groups — Skirmishers and Regiments — that have special rules that control events such as saving throws, a Hide action, and becoming isolated, a condition where a unit gets too far from a friendly unit and will roll ad disadvantage on attack rolls.

* Players do bring some fun and interesting actions for mob scale rules — not only do players retain abilities such as spell casting and feats, they are allowed to move in and out of stands and units, joining for opportunities such as Incite (grants advantage) or Rally (reverse effects of low morale).

* As with Chainmail, terrain can become important. Movement over certain terrain can be faster or slower, and high ground grants advantage over opponents below. And as with Chainmail, there are victory conditions to consider — with Chainmail, both players typically agreed on certain conditions, but with these new rules it’s still the DMs call (because the rules do call for setting up the fight well as well as creating the terrain and other special areas of the map). Victory points are awarded based on conditions, and the winning army is the first one to reach 10 points. (I especially enjoyed page 8 where it talks about creating the objectives that can earn points for a side.)

Note: One bit of combat that came as a welcome surprise is reminiscent of Chainmail — many combat situations are resolved simultaneously. Two sides each attack, one at a time, but if a certain unit or solo is killed, that unit or solo still determines the outcome of its attack before actually being removed from play. COOL! (Also, solos — including players — who die get 10 death saves instead of 3… given that a combat round is now a full minute, this makes sense to give players many more chances to have friendlies come around to heal and resurrect.)

* Morale also makes a reappearance. A flat rule is in effect, however — when a unit loses 50% or more of its number, then a morale check is made. It uses a Wisdom DC 10 roll, but if a player, for example, is leading a unit, that player’s Wisdom modifier can be used if it’s higher than the creatures’ highest modifier! A failed save “breaks” the unit up and it begins a Retreat action, but any solo (including a player) isn’t part of the broken unit and doesn’t have to Retreat. Of course, a player can use the Rally action to undo the Retreat.

* Both the Attack and Cast a Spell sections contain a good enough set of rules (without going on for pages and pages) for both types of combat to be easily initiated by players controlling groups. Spells do change a bit, however, when it comes to Range and Area of Effect, and there are additional rules for Advantage and Disadvantage that must be remembered when dealing with stand-vs-stand or solo-vs-stand situations.

* The Regiments grouping will be of particular interest to Chainmail fans (and other war games) that use specific types of ranks and orders when keeping combatants together as a large group. What I most like about this new set of rules is that while there are some special features for Regiments, they aren’t large in number — just three possible configurations when in play… Aid, Defend, and March. (Note that the Dash section doesn’t specify in parenthesis what types of groups can use it, but the text makes it clear that it’s available for a Unit — that includes both Skirmishers and Regiments.)

Again, the description of the Unearthed Arcana rules state:

These game mechanics are in draft form, usable in your campaign but not fully tempered by playtests and design iterations. They are highly volatile and might be unstable; if you use them, be ready to rule on any issues that come up. They’re written in pencil, not ink.

So, obviously… DMs and players should use at their own risk when it comes to using their favorite characters in the role of a Commander.

“Also, solos — including players — who die get 10 death saves instead of 3… ”

It looks like you roll ten saves in a row at the end of the round, since each round is ten times longer than normal. This gives you considerably more chance of dying before someone can come to your rescue.

I’m sure you know about this… http://takzu.com/bd_pdfs/Blackmoor%20JG37%20The%20First%20Fantasy%20Campaign.pdf

I tried to learn D&D by myself as a 12-year-old in 1977 with the three booklets… I had a great time (small town … no other players). I must have read the example of play 1000 times… I bought the booklets because a family friend brought me onto the Warden.. I don’t remember what “I” was other than I had Radiating Eyes… Metamorphosis Alpha … good stuff.

Thanks for your words.

Hey, just thought I’d drop you a link to this tool I recently made to handle some of the Chainmail issues you discuss. Great article btw. I painstakingly combed the rules and laid them out so that we can actually fight battles in and AD&D setting. Check it out here: https://www.thebluebard.com/blog-1/chainmail-for-ad-d