Every fall, well over a hundred thousand board gamers converge on Essen, Germany, for the biggest gaming convention in the world, Internationale Spieltage (SPIEL). It’s on my bucket list—one of these days I’m hoping to attend, but these days I’m staying closer to home. However, thanks to a new board game from LudiCreations, gamers like me can get a tiny taste of running a booth at Spiel. Welcome to ESSEN.

At a glance: ESSEN is for 1 to 4 players (up to 8 if you combine copies of the game), ages 12 and up. It takes 30-60 minutes to play (expect longer the first time you play, and depending on the number of players, of course). With the complexity of the game, I’d say the age recommendation is pretty close. Experienced 10-year-olds may get the hang of it, but you probably wouldn’t want to go too much younger than that. ESSEN is currently raising funds on Kickstarter, and the pledge level for a copy of the game is $50, though if something substantial is added to the game the price goes up to $60 or $65. LudiCreations may lock down the number of $50 copies during the campaign, in which case the price is $68.

Also: LudiCreations has created a module for Vassal—a program that lets you play board games over the internet. Rather than a print-and-play, you can try out the game online by signing up here.

Components:

- 4 double-sided player boards

- 8 wooden player tokens in 8 colors

- 1 double-sided central board

- 120 regular visitor tiles

- 40 extra visitor tiles

- 3 sale/promotion tiles

- 6 ad tiles

- 3 accountant tiles

- 2 large wooden cubes

- 2 small wooden cubes

- 4 Queue tiles

- 16 Seller tiles

- 9 Demand tiles

I should note that LudiCreations is taking a different approach than I’m used to—rather than physical prototypes, they’ve created a module for Vassal, a game engine that lets you play games over the internet or email, and they’ve invited people to try out the game. I played a demo game with Iraklis of LudiCreations and Harry-Pekka Kuusela, the game designer. So I can show you some of the artwork for the game and the screenshots from the Vassal module (which are completely unfinished design), but I don’t have the usual prototype photos. (This was my first time using Vassal, but I’ll focus on the gameplay of ESSEN in this post rather than the Vassal interface.)

The artwork will be pixel graphics, with an isometric view of the convention floor. Here’s an example of three of the visitors (which you’ll try to convert into sales, of course).

The game will be filled with nods to gaming culture. For instance, the player boards (which represent booths) will be themed—Eurogames, Ameritrash, RPGs, party games, and so on.

How to play

The goal of ESSEN is, of course, to make the most money over the course of the four-day event. Most of the money comes from selling games to visitors, but there are also three bonuses you can earn. You can download a low-resolution version of the rules here.

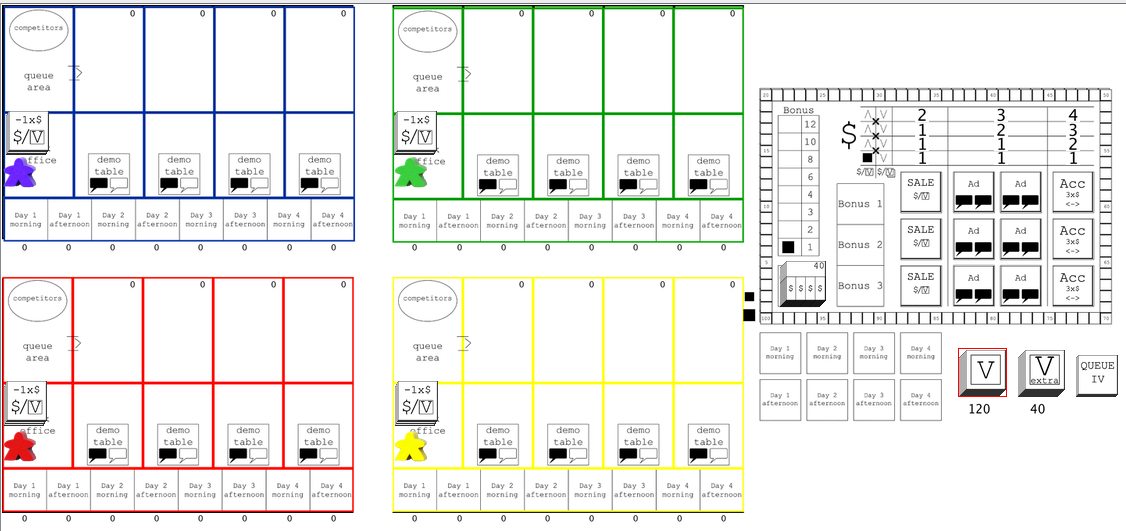

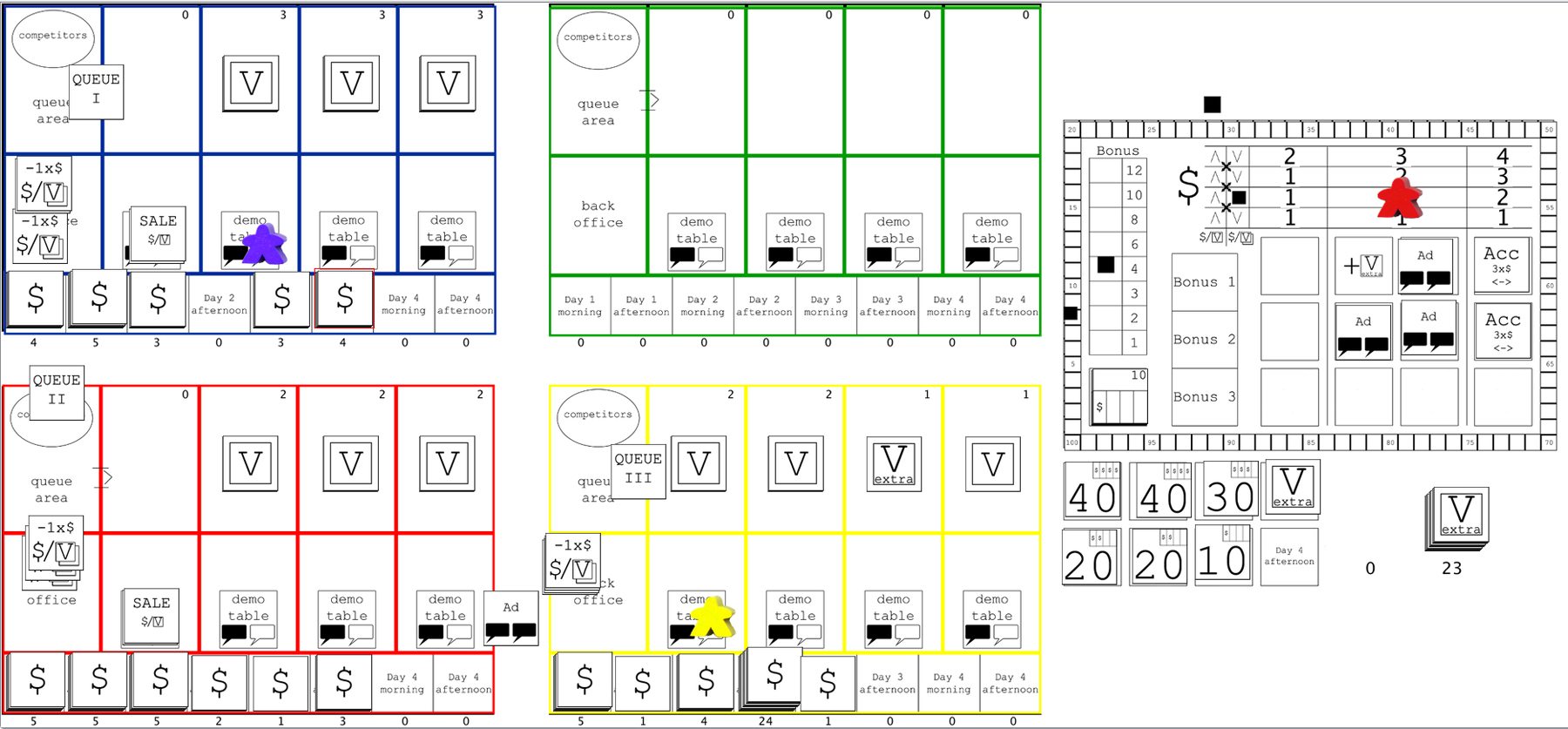

The main board tracks a number of things: total sales figures for the last sales period, highest total sales, bonus level earned, and the current price of special options like sales, ads, and accountants. There’s a pile of visitors (30 per player), some extra visitors (representing potential visitors that may be drawn in with advertising), and a stack of tiles that indicates the number of visitors in a sales period and the demand for buying games. Each player starts with a player board, a meeple, four seller tiles and $3 in cash.

The game takes place over the course of eight rounds, representing the mornings and afternoons of the four-day convention. Each round, you’ll decide how to use the four tables at your booth and decide where to send yourself (your meeple) to work.

The four tables can be used as demo tables, generating buzz for your booth (represented by the little speech bubbles), which can let you poach visitors from neighboring booths. Or you can sell games—in which case you put the selling tiles on the table, covering up the “demo table” icon. It costs $1 for each table you’re selling at.

After everyone in turn order has decided how many tables to use for selling and demos, then everyone decides where they’ll send their meeple. You can sell at an additional table without paying the $1 cost—simply put another selling tile out and put the meeple on it. Or you can help generate more buzz if you have at least one demo table left: you place the meeple on the blank speech bubble and it generates one more buzz for your booth. You can also try to steal customers from other players by hanging around their booths, handing out flyers and hollering about how great your games are—in this case you place your meeple in the “competitors” area of their booths.

There are also a few places you can go on the main board to buy things: Sale/Promotion tiles let you turn visitors into money at a 1:1 ratio even when sales are down (but more about that later). You can also buy ads, which have a couple of effects. First, they generate two more buzz for your booth. Removing the ad tile reveals an extra Visitor on the board, which indicates that in the next round there will be extra visitors coming to the convention. Finally, you can hire an accountant, who allows you to “massage” the books—this mostly matters for those end-game bonuses.

The price of these three items depends on how the market has been. There’s a little cube that tracks whether total sales went up or down for the last period. When they go up, the cube moves up on the left side of the track, and it raises the price of sales, ads, and accountants. When total sales go down, the price of everything drops, but there’s another consequence: when you sell games to customers, you’ll only get $1 for every two customers, unless you’re running a promotion.

Once everyone has placed their meeples, then the visitor/demand tile is flipped over into the appropriate time slot. The current tile indicates the number of visitors that will be coming to the convention at that time. The next tile in the stack, just revealed, indicates the demand for purchasing games (and also the number of visitors that will be coming in the next time slot). The tiles have 10, 20, 30, or 40 visitors, and will indicate between 1 and 4 stalls for buying demand. You take the number of visitors indicated (along with any extra visitors earned from earlier advertising), and divide them evenly among all the players, with extras going to those first in turn order.

These visitors are then divided evenly among the four stalls in each player’s booth—although if there are competitor meeples present, they also get a share of the visitors. Once all the visitors are placed in the stalls, then you look at the next demand tile to see how many stalls it shows. The visitors from that many stalls will buy games at your booth—as long as you have enough selling tables. You’ll get either $1 per visitor or $1 per two visitors, depending on the previous round’s total sales. The Sales/Promotion lets you sell to your first stall at a 1:1 ratio regardless. Any visitors you sold to are flipped over, showing the $ on the back, and placed in a stack on your player board in the appropriate time slot.

Then it’s time for the buzz. You compare the amount of buzz you have with your neighbors, and if you have more, you get to take one stall’s worth of visitors into your queue area for the next round. Any visitors still hanging around your booths at your demo tables (or those selling tables that exceeded demand) go into your queue area. Finally, any visitors you poached by using your meeple as a competitor come to your queue area. You put away selling tables, retrieve your meeples, and start the next round. At the end of each day (that is, every two rounds), you’ll return the sales/promotion tiles and ads to the main board.

At the end of each round, you also check the total sales from everyone, which is marked with the small wooden cube. If it went up from last round, then the little cube on the price track moves up (and to the left, if it can). If the total sales were lower, then the little cube moves down and to the right. Each time the maximum total sales (marked with the large cube) increases, the bonus level also moves up.

At the end of the four days of the convention, you count up all the money you’ve made, and also check which player earned the three bonuses. The first bonus is for the longest streak of increasing sales. The next is for the highest low period—that is, you compare your lowest sales period, and whoever has the highest number wins the bonus. Finally, the third bonus is for the player who has the most visitors left in their booth area at the end of the game. Each bonus is worth the amount of money indicated on the main board.

The accountant, which you can hire from the main board as an action with your meeple, lets you move three money tiles on your board—this may help you get one of the bonuses, if you can increase your lowest sales period or stack things up so that you have a long increasing streak.

At the end of the game, the player with the most money wins!

Two more things: if you have two copies of the game and combine them for a 5-8 player game, there are more end-game bonuses. And if you opt for solo-play, there’s a sort of AI that plays against you. I haven’t tried those versions myself.

The Verdict

Although I played ESSEN over Vassal with rudimentary graphics and basically no artwork whatsoever, I found it pretty fascinating. I’ve never run a booth at a convention—and I’m guessing the majority of board gamers haven’t either—but I think the game certainly feels the way I imagine it’s like. I do like the way that the various game mechanics reflect real-life behavior to some degree, and it’s apparent that the designer and publisher have experience with real-world Essen.

There are a lot of choices to make throughout the game, but one of the key choices is the balance between buzz and income. Buzz brings in more visitors to the convention and lets you snag visitors from your neighboring booths, but just getting a bunch of visitors isn’t enough: you have to get them to buy games!

The buzz vs. income tug-of-war reminds me a little of Epic Resort—in that game, the number of tourists you had at each attraction determined the amount of Flair and Gold you earned—more tourists is more Gold, but fewer tourists is more Flair, which allows you to attract more tourists and Heroes later.

Throughout the game you’ll have to guess how many people will be buying games each period—ideally you match demand exactly, so you don’t spend extra money for tables that don’t sell, or run demos when there are customers lined up with their wallets open. But because of the distribution of the demand tiles, you’ll have a better guess late in the game than at the beginning—in the last round you’ll know exactly which tile is left. Using this increasing knowledge to your advantage is important.

The way sales work is tricky—when income went down in the previous sales period, it takes two visitors to make one cash—in those cases, sometimes you don’t want to sell at all of your tables, because you may spend one cash to turn it into a sales table, and then only make one back. The sales slumps are hard to turn around, and generally involve buying some advertising to get an influx of visitors.

Another thing that fascinated me was the fact that the cash is on the back of the visitor tiles—and there are a limited number of visitor tiles in the game. So if that stack runs low, the only way to replenish it is if the players spend money, thus putting visitors back into the supply. So even if the Demand tile shows that there will be 40 visitors coming, it’s restricted by the number of available tiles.

There are a lot of interesting dynamics in the game, too, because of the way poaching customers works. As you go around and assign your single meeple worker, you have to be aware of what your opponents may do. If you decide to put an extra sales table out, then your opponent might generate more buzz and steal customers from you. Or they might just come over to your booth and take even more.

Finally, the end-game bonuses make the Accountants valuable, if you can manage to arrange your earnings in a way that gives you bonuses. It’s tricky, because many of your actions spend money, which takes money away from the previous period’s earnings first. So if you’re going for “longest streak of increasing sales,” you have to avoid spending too much money from the latest period … or hire an accountant to cook your books. I thought I’d had the “highest lowest sales” locked in because everyone else had at least one period with no sales—but then an accountant shifted some sales, and I lost the bonus.

There’s a whole lot going on in ESSEN and it can be a bit overwhelming at first, but it starts to make sense once you start up and see how all the various things interact. The problem is that it’ll probably take at least one full play before you can pick up enough strategy to really compete.

I love meta—games about games, books about books—so ESSEN appeals to me. The logistics of balancing sales and income, future visitors and current buzz: it’s a bit of a brain-burner, too, but I like this sort of thing. If you like games about games and you’ve been to gaming conventions, this game may really click for you.

One note about the Kickstarter campaign itself: LudiCreations’ campaigns tend to be a little different from many others. Rather than the now-typical stretch goals that add more and more stuff with each funding level hit, instead there’s a small list of improvements that can be made, which then increase the price of the game. So early backers will get a lower price that’s locked in, and if things get added, the price goes up and later backers pay that higher price. At any rate, if you haven’t backed a LudiCreations Kickstarter project before, you should pay attention because it might not be set up the way you expect.

[UPDATE: In this case, all of the improvements are included up front, so there aren’t any additional items being added. However, the $50 pledge level is somewhat like an early bird price: LudiCreation keeps that open until they get a sense of how many total copies they’re going to be producing and delivering, at which point they may lock it down. The pledge price that actually reflects the costs is $68. There are also higher levels to be included as a pixel sprite on an extra Visitor tile, or even get yourself on the box cover.]

Although I’ve only gotten to play once so far, ESSEN definitely grabbed my attention and I’m interested in playing it more. It has a nice blend of different mechanics and, as a bonus, I think it’ll make people think a little more about what goes into being a publisher at a convention. Granted, I think the game is still a lot simpler than the actual experience, but you do get a taste. For more information, check out the ESSEN Kickstarter page.