You’ve heard of the scares, the parental worries. You’ve probably experienced the witch-hunts and moral panics led by the older generations.

Skateboarding is bad for you. Video games, rock and roll and Dungeons & Dragons are all bad for you. Even Snapchat is bad for you.

“You” being the unsuspecting, vulnerable youth of America, helplessly corrupted by the unseen and malevolent forces of pop culture, the media and technology.

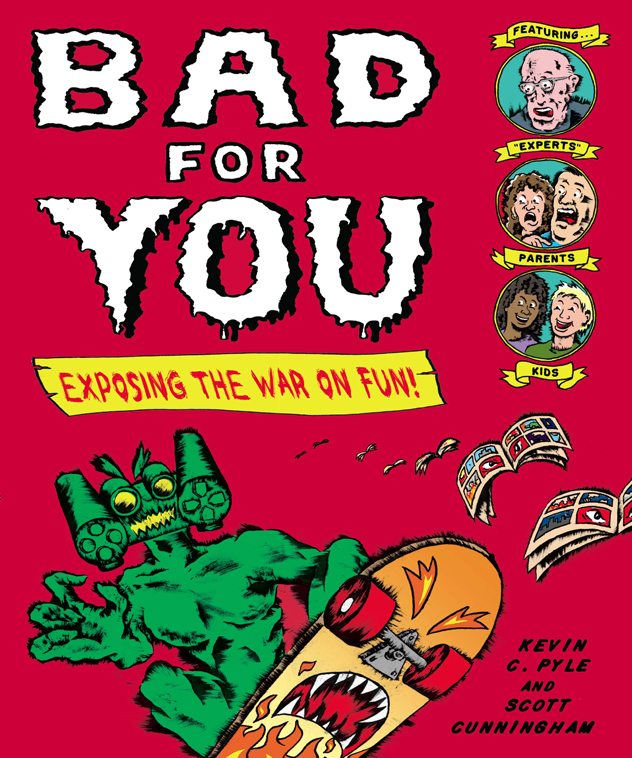

As the book Bad for You: Exposing the War on Fun explains, what is bad for kids and teens, and bad for society, goes way back to Plato, who worried about a new dangerous trend of his day: the written word. Authors Kevin C. Pyle and Scott Cunningham have created an illustrated tour through these cultural freak-outs. In the words of their book’s website, the book is “a historical look at the hysterical horror adults have felt about kids.” Pyle, who did the artwork, and Cunningham categorizes these horrors into categories like “comics,””games,” “technology,” “play,” and “thought.” It’s a fun, surprising and biting survey, and Pyle’s comic book presentation keeps the pages lively and entertaining.

Pyle, age 50, is the author of the graphic novel Blindspot; Cunningham, 57, is a writer for Heavy Metal and Mad Magazine. I recently had a chance to ask them both about the origin of their book, their own childhood experience as “bad” kids and having over-protective parents, and the current trend of “helicopter parenting,” as well as whether anything they investigated actually IS bad for you–farting on the bus, for example–among other questions. What follows is our three-way conversation.

GeekDad: What inspired you to write Bad for You?

Kevin C. Pyle: I was in a conversation with my editor at Henry Holt about my previous graphic novel which centers around a Japanese Internment camp. We were talking about moments of government hysteria when constitutional rights seem to go out the window. I casually dropped a reference to the congressional hearings that sparked comic book burnings. That led to a whole conversation about what are referred to as “Moral Panics” that were centered on kids. It just seemed too good an idea not pursue. But I knew it was a huge subject and I needed help with a comedic voice, so I brought Scott on as partner cause of his work writing for Mad Kids. Plus I know him to be a great researcher.

Scott Cunningham: When Kevin approached me with the idea, I was immediately taken with the concept. If you work in comics, the whole comic book burning and rise of the comic book code is fairly well known—so much so, that you tend to forget how obscure it is to most folks (like Kevin’s editor at Holt… who works in kids’ books). Our thought was: How many other times in history has fear over what kids enjoy led to censorship and panics. The answer is a lot! As we dug deeper, what was interesting was seeing these patterns emerge. Sometimes, it seems interchangeable: The headlines from the 1800s about penny dreadfuls and their ghastly influence on young readers are worded almost exactly like what critics of violent video games are saying today about their influence on kids.

GeekDad: Did either of you have over-protective or paranoid parents who disapproved of your childhood interests, or thought your hobbies would corrupt you? If so, give details. How old were you and during what years did this happen?

Pyle: I dropped a large portion of my summer job earnings at the local video arcade and was deep into skateboarding but don’t remember any push back from my parents. In fact my Dad built me skate ramp. I was actually a kid who, for a short time, got in a fair amount of real, as in prosecutable, trouble. So I think my parents welcomed my obsessions with skateboarding and arcade games with some relief.

Cunningham: I started reading comics when I was three, and it was something my parents really encouraged me to do. My dad would bring a comic for me almost every day when he came home from work—it was a way for us to connect. So learning more about how Fredric Wertham’s ideas had such a negative impact on how comics were viewed by adults in the late 1940s and 50s really pissed me off.

I grew up in a semi-rural area of Missouri so instead of going to local playgrounds, which seemed pretty boring to us, the kids in the neighborhood would go into the woods and build a treehouse or fort, or find an abandoned shack somewhere and destroy it, or go fishing, or pitch a tent in the backyard and sleep there all night. And I was considered the wimpy kid among my friends because I was a little nervous when they were designing gasoline bombs! Where I grew up there was no comic book burnings… but there were mass plastic army men burnings. I ask you, how can children grow up today without at least melting a few plastic army men?!

GeekDad: As you researched the many topics for Bad for You, which area or weird story shocked you the most?

Cunningham: I never played Dungeons & Dragons as a kid so that was a surprise to me when we researched the panic that it caused. I mean, I vaguely remembered reading headlines about the fears some critics had of the game, but it did shock me how strong the reactions where, what with Patricia Pulling and her group B.A.D.D.—which stands for Bothered About Dungeons & Dragons. Believe me, when you start looking at the campaign she and her group mounted against the game, they were more than a little “Bothered” by D&D. They thought it was satanic and induced suicide in the feeble-minded players who couldn’t distinguish between fantasy and reality. In fact, that’s the same complaint that people have had about entertainment for kids from the beginning—and by beginning I mean WAY back in the day… like, Plato’s day. It’s a reoccurring theme—the ultimate “go-to” position that adults take when claiming they are protecting kids from bad influences. It’s the belief that kids have to be protected from scary literature, or comics, or movies or TV or video games, because they’re minds are too unformed to tell the difference between what’s real and what’s made up. Of course, as adults becomes used to whatever the latest—the newest—panic is over, society becomes more relaxed and life goes on. Until the next panic.

The other thing about D&D that I didn’t realize, is just how influential role playing games were to the open-ended, multiple storyline structure of video games. D&D, you could say, is in the DNA of many video games–and not just the fantasy-oriented ones, either.

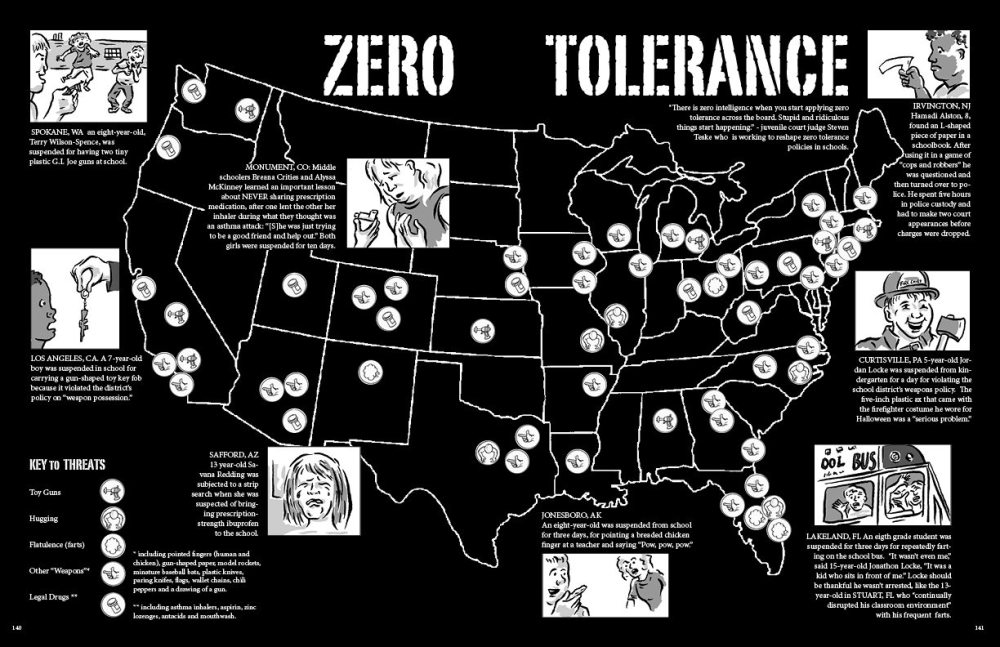

Pyle: Ditto on D&D for me. And even though I knew about the “Zero Tolerance” hysteria I had no idea how widespread and absurd some of the cases are. Kids being suspended for farting on the bus, or pointing chicken fingers at teachers, or a kindergartener who brought a plastic ax as part of his Halloween fireman costume.

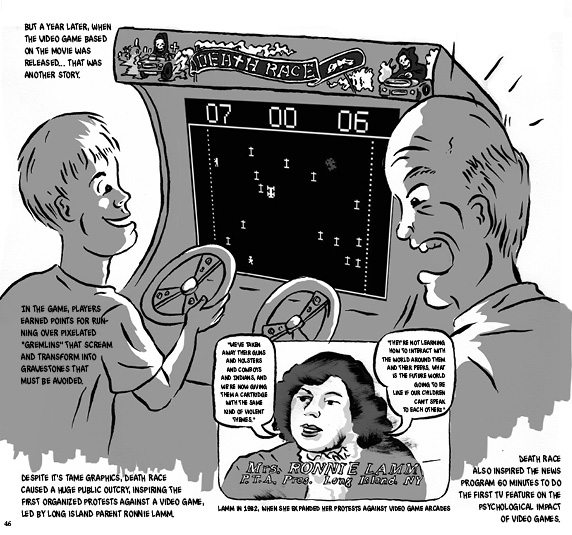

GeekDad: Death Race, the video game 1976 that you talk about in your book—jeez, it seems primitive today, and yet what an outcry it caused then. Now we have Call of Duty, about a zillion times more realistic. What lesson do we learn from the history of demonization of video games?

Cunningham: Just wait. Each new wave of fear over the latest technology that interests kids is just that: a wave. The wave comes, it crests, and then it crashes against the shore and fades away. That’s partly why we chose to create the timelines in the book, like Youth-a-Phobia or Fear of the New, to give a historical view of these hysterical reactions. But with the distance of time, all these panics start to look foolish and quaint.

Pyle: Especially that “pernicious excitement” of chess embraced by children “of very inferior character.”

GeekDad: In my day, growing up in the 1970s and 1980s, life for a kid was much wilder, and unsupervised. I grew up with no helmets, no cel phones, “Get lost until supper time” style of parenting. Why do you think previous eras were more permissive, in some ways–though of course your book details all ways in which parents have freaked out about all kinds of things throughout history?

Cunningham: Litigation and regulation. It’s funny, because I think Kevin and I would describe ourselves as pretty liberal, even lefty, types. But Bad for You has really been embraced by libertarians and anti-government groups—which is a bit of a surprise for us. We got a really great review in Reason Magazine, for instance, which lead to me getting interviewed on a right-wing radio station in Reno, Nevada and both of us being interviewed for “The Wonderful World of Stu” on BlazeTV, Glenn Beck’s channel. But that’s where the research took us—that’s where the data led. Over-regulation and too much litigation has caused cities to create safer (i.e. more boring) playgrounds and try to control public space with more policing and curfews, so kids have nowhere to hang out and just be kids.

Pyle: But some of the more serious manifestations of this phenomenon are falling primarily of kids of color. The increased police presence in schools is resulting in what some activists are calling a “school to prison pipeline” where in behavior that would have once resulted in suspension is now pulling kids into the justice system.

As long as we’re dipping into politics, I think there is a general drift towards authoritarianism towards individual freedom that is coinciding with a solidifying of corporate and state power. On some level I hope Bad for You contributes to kids thinking about how their lives are affected by these forces. But that doesn’t really answer your question. I can’t really say why there’s been a shift but one thing that seems true is that it’s a very American phenomenon. I hope there is a sociologist out there studying it right now.

GeekDad: Now parents seem to lock in and dictate every waking minute of their kids’ lives. What do you think explains the rise of helicopter parenting today?

Pyle: I feel the media’s insatiable need to keep viewers on the hook is part of the dynamic, and it seems fear and anxiety are the emotions they are quickest to exploit. It’s the same with weather, crime, health issues, you name it.

Cunningham: Yeah, there are more sources for news and those sources are providing news 24-7—and they’re all struggling to grab the viewers’ attention. When there’s a tragedy, something such as a school shooting or a child kidnapped, the stories are examined in detail and repeated endlessly by various cable and internet new sources and the impression parents get from the wall-to-wall coverage is that these tragedies are constant and increasing with each year. In fact, statistics indicate that it’s the safest it’s ever been in America to be a kid and youth crime rates continue to decrease since they peaked in the early 1990s.

Another possibility—though I really don’t have any data for this, so who knows—might be that because parents tend to be older now before they have kids, that they are therefore more cautious. The person I was in my 20s was a lot looser and more likely to not be as worried about all the things out there that could kill or maim or psychologically damage a kid; compare that to the person I was 15 years later, when my daughter was born, and you’re talking about a much more cautious person.

GeekDad: Is there anything you considered including in your book to debunk, but then realized, “You know, this kinda IS bad for you.”

Pyle: We had some struggles about whether fears over cyber-bullying has reached hysterical levels and I think it has in some cases. But the flip side of that is it seems like a situation where the technology really has changed the activity and I wouldn’t want a cyberbullied kid to feel we were insensitive to their experience.

Cunningham: Yeah, I’m still not sure about that decision. I feel like we’re in the midst of this cyber-bullying panic and so, without the proper perspective one needs to do the analysis, we backed away from exploring it further. But I believe that over time, cyber-bullying will be viewed as another overreaction to the situation. I was bullied a lot as a kid (remember–I was the wimp who wouldn’t set off gasoline bombs in the woods!), and let me tell you, getting the crap beat out of you regularly is not so great. I think I would have been happier to have been cyber-bullied rather than physically bullied. But maybe that’s just me.

GeekDad: Anything else you want to add?

Pyle: I think given how the positive reaction to this book has crossed political lines there may be a cultural shift underway. But I think more adults need to understand what it’s like to be a kid today.

Cunningham: It would be nice to think of Bad for You as being part of another wave… one that is the opposite of panics in the past over what kids like to do for fun. Instead, how about a wave of parents becoming more relaxed about what their kids are doing; a wave of allowing them more freedom to just be a kid. We’ll have to wait and see.