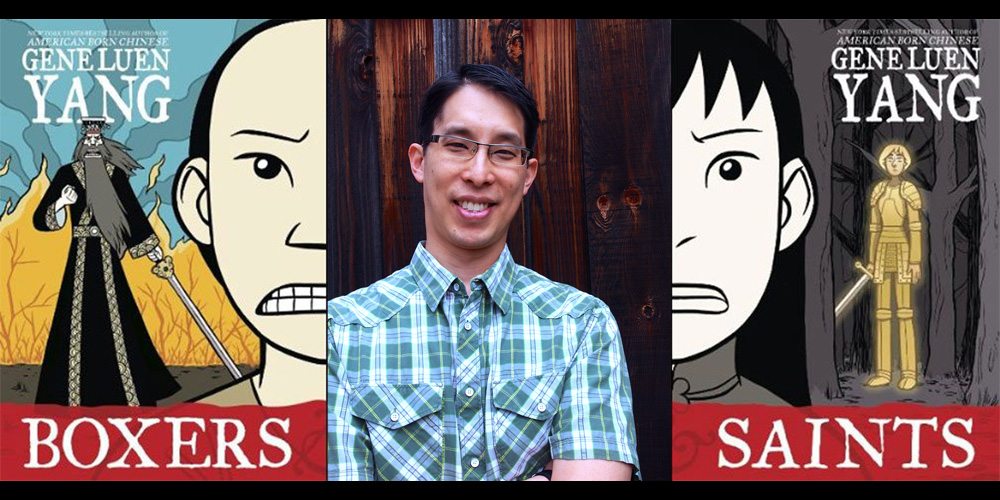

This week, First Second Books releases Boxers & Saints, a two-part comic book by Gene Luen Yang that approaches the Boxer Rebellion from two perspectives. I mentioned the book in my Serious Comics series earlier this summer, and I highly recommend the set. I got the chance to interview Yang about his books.

GeekDad: What inspired you to write Boxers and Saints, and how did you settle on this two-book idea?

Yang: I grew up in a Chinese American Catholic community in the San Francisco Bay Area. In the year 2000, Pope John Paul II canonized a group of Chinese Catholic saints. This was the first time Chinese citizens had been honored by the Roman Catholic church in this way, so naturally the folks at my home church were super-excited. There were all sorts of celebrations and special masses.

When I looked into the lives of these saints, I realized that many of them had been martyred during the Boxer Rebellion. I vaguely remembered the Boxer Rebellion from my high school history class, but what little I read about the Chinese saints prompted me to find out more. The Boxer Rebellion is fascinating on so many levels. It was an important inflection point in the relationship between East and West. It still affects the world today. The Boxer Rebellion was the climax of China’s “century of humiliation.” China’s deep desire to be respected among the nations of the world, its pursuit of technology and economic power and even the Olympics, is in many ways a response to the 1800s and to the Boxer Rebellion.

As an Asian American, I grew up in both Eastern and Western cultures. When I read books about the Boxer Rebellion, I found myself torn. I couldn’t decide who the protagonists were. And that’s why I did two books for this project. The protagonists in one are the antagonists in the other.

GeekDad: Why is Saints so much shorter than Boxers?

Yang: Saints is about half as long as Boxers. Lark Pien, who colored both books, colored Saints mostly in greys. Boxers is full color.

Boxers is about the Boxers, young Chinese teenagers who marched through the countryside fighting foreign soldiers, missionaries, and Chinese Christians. Saints is about the Chinese Christians killed by the Boxers. Their stories are very different—they don’t match up perfectly, so I knew early on that Boxers would be much longer. Historically, the Boxers went on an epic journey, from village to village, all the way to the capital city. The motivating question for their story is, what does it mean to be a hero? I wanted it to read like a comics version of a Chinese war epic, full of color and drama and blood.

The Chinese Christians of history had a much quieter story. They basically stayed in their villages, defended them, and were killed. The motivating question here is, what does it mean to be a saint? Because humility is such an important part of our concept of sainthood, I knew their story would be much more humble than the Boxers’, shorter and more intimate. I tried to draw from the aesthetics of American autobio comics here. I didn’t use rulers to draw the panel borders, to give it a more hand-made look. I used my wife’s handwriting for the caption boxes so that the whole thing would read like a journal.

Boxers is the journey. Saints is a journal that was found on the journey.

GeekDad: Many of your stories incorporate your faith to some extent, but usually religion isn’t central to the story. What was it like having these two clashing religions and cultures front and center for these books?

Yang: I couldn’t do a story about the Boxer Rebellion without talking about faith. It was such an important part of how people defined themselves back then. Even today, many people use religion to find their place in the world. Religion—stories in general, I’d say, as religions can be seen as collections of communally-held stories—can give us a history that extends beyond ourselves. This was certainly true of the Chinese at the time, both those who held onto traditional Chinese beliefs and those who adopted Western ones.

And I hope that my books aren’t just about the clash between religions—I wanted to explore their overlap too. For instance, I tried to highlight the commonalities between Christ and Guan Yin, the Goddess of Mercy.

GeekDad: I was surprised to find that Vibiana (the protagonist in Saints) wasn’t what most readers would consider a devout Christian throughout much of the story—instead, she was interested in being a Christian because she misunderstood the faith. Was there a particular reason you chose to tell her story this way, rather than having it center on a more conventionally devout Christian?

Yang: An idea I encountered in my research was that the early expansion of Christianity in China was driven primarily by politics and social dynamics. Early Chinese Christians didn’t have authentic spiritual experiences within this Western religious paradigm. They were just outcasts who couldn’t find a place in Chinese society, who needed political power.

While I’m sure that was true for many early Chinese Christians, I don’t buy it completely. It doesn’t fit with my experiences growing up in that Chinese Catholic church. Most of the adults around me weren’t there for politics or social dynamics or anything like that. They were there for spiritual reasons. They got something out of it, something necessary and personal. Also, if it were true for the movement as a whole, how do you explain the expansion of Christianity in China after the foreigners were kicked out? When there was no political power to be had by converting? There had to be an authentic spiritual experience at some point, some deep, personal need that was met.

So that’s how I structured Vibiana’s experience of Christianity. She’s first attracted simply because she’s an outsider, for political reasons in a sense. But at the end of her life, she has an authentic spiritual experience.

GeekDad: Both Vibiana and Little Bao have visions that inspire them: Joan of Arc and Ch’in Shih-huang. And both of them begin to have doubts about their visions. It made me wonder: were these visions supposed to be “true” for each character? Or are they meant to be questioned?

Yang: That’s a great question, and it’s a question I can’t really answer. I get asked that about American Born Chinese a lot. Is the transformation of the protagonist real, or is it just in his head? To be honest, I couldn’t decide, so I wrote the book in a way that allowed the reader to decide. I did the same for Boxers & Saints.

GeekDad: What do you hope readers get out of reading Boxers and Saints?

Yang: First and foremost, I hope readers find the books compelling enough to read to the end. I hope I told good stories.

I guess I also hope they’ll want to learn more about the Boxer Rebellion and Chinese history in general. As China becomes a global economic player, the Boxer Rebellion and other East-West historical events will grow in importance.

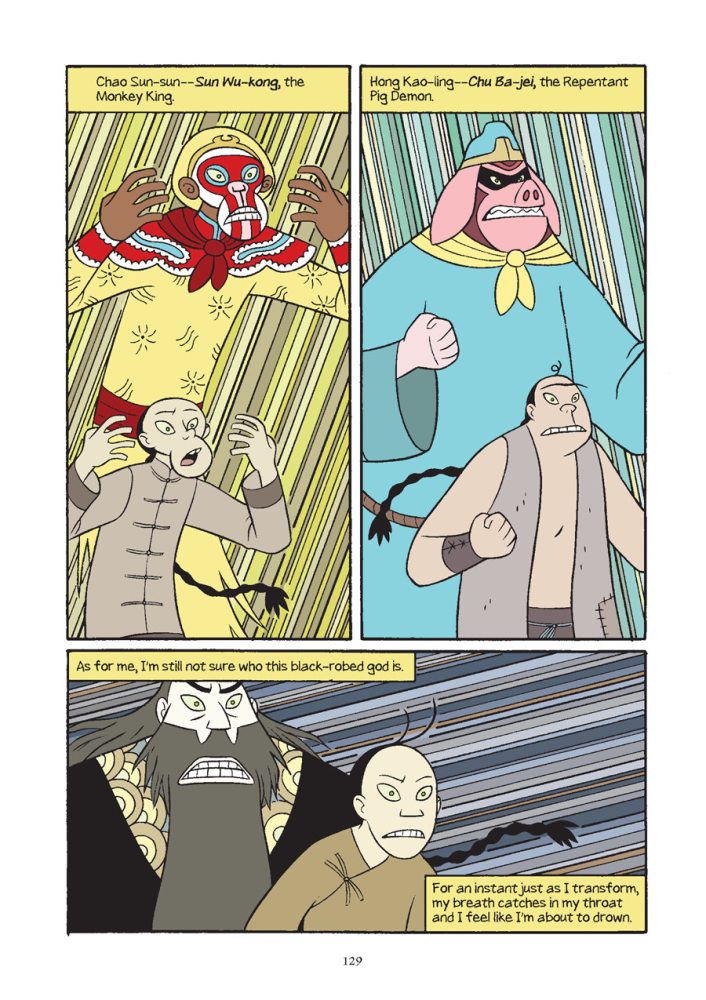

GeekDad: I found myself really drawn to the portrayal of the ancient Chinese gods in Boxers—I have only a tiny bit of knowledge about the stories—and I loved the way you illustrated them. Any chance you’ll take on the legends of Sun Wu-kong, the Monkey King?

Yang: Man, I love the Monkey King. I’m a huge Monkey King fan. He’s already shown up in two of my graphic novels, American Born Chinese and Boxers. I want to do more with him, but I don’t think I’d ever do a straight adaption of Journey to the West, the original Monkey King novel. I mean, there are so many good ones out there already. Heck, Osamu Tezuka did his own version of Journey to the West. Osamu Tezuka! The God of Manga! What could I possibly add to the world by doing my own?

GeekDad: I loved the Chinese opera versions of superheroes you posted on your site. Could you share with our readers what that was about?

Yang: Earlier this year, I drew Chinese opera versions of the Avengers and put them up on my website. I wanted to highlight the similarities between Chinese opera and comic books. Chinese opera was the “comic books” of the Boxers. It was the Boxers’ pop culture. Like American superheroes, the heroes of the Chinese opera wore colorful costumes, had magic powers, and fought battles on an epic scale. The Boxers were inspired by them, the way modern-day geeks like me are inspired by superheroes. The Boxers wanted to embody their heroes, so they came up with a ritual that would call them down from the heavens. These heroes, these gods, would possess them and give them superpowers so they could fight the foreigners. It all points to the importance of story. Pop culture is powerful stuff.

GeekDad: I’d love to see a Chinese opera Avengers. Let me know if Marvel calls!

Thanks again to Gene Yang for the interview, and to First Second Books for providing review copies of Boxers & Saints! Visit GeneYang.com for more of his work, or FirstSecondBooks.com to see some other great comics.