You may not know that Lego Mindstorms gets its name from a book by Seymour Papert called

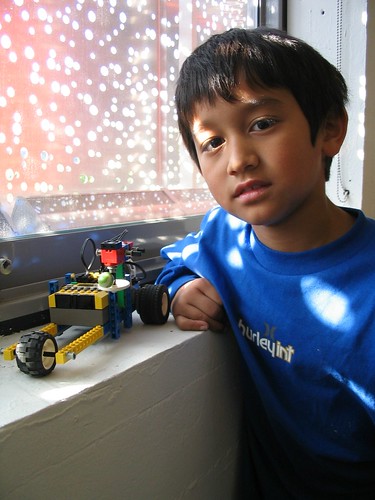

Mindstorms: Children, Computers, and Powerful Ideas. I first read this book in the 1980s, and I took its basic precepts to heart when I started teaching Lego Mindstorms classes to younger kids (that’s one of my students in the photo). Papert’s ideas continue to guide me in my Flash videogame programming classes for high school kids.

Papert, a student of developmental psychologist Jean Piaget, has much to criticize about the way mathematics are taught to children. Although he was writing in the late 70s, the situation is not much better today, even though we have much better tools available to us for teaching math.

As a long-time programmer/hobbyist, math is one of my most powerful tools, and I now have a deep appreciation for it, but things weren’t always this way. Throughout high school, I failed most of my math and physical science classes, preferring ‘soft’ classes like English and music. It wasn’t until college, when playing around with analog music synthesizers and computer graphics programming, that I began to seriously play with math. By approaching math through my interest in art, I was finally able to appreciate my own long-dormant talents in this area. I still wonder how much more I could have accomplished if I had begun this activity when I was younger.

The problem with mathematics education is that we are too far removed from the subject being taught. I was one of many high school students who believed that math had no connection to my life, and that I would never need to do more than balance a checkbook or count the correct change. The universe in which math made sense seemed far, far away from my day-to-day existence.

When children are young, they are incredibly facile learners. If your child were to spend some time in France, it is likely he or she will pick up quite a bit of French. "What would happen," asked Papert, "if children who can’t do math grew up in Mathland, a place that is to math what France is to French?"

In the 1970s, Papert constructed a kind of Mathland using the LOGO programming language, and robotic turtles that could draw pictures. These tools were used by very young kids, who would not ordinarily be exposed to concepts like angles and polygons. Papert’s book, Mindstorms, recounts this fascinating story.

Later Papert participated in educational projects at MIT which used the forerunners of the Lego Mindstorms system.

A key component of Papert’s educational philosophy is self-directed learning. As kids build cool things in Mathland, they naturally encounter problems which require creative mathematical solutions. As a result, formerly abstract mathematical concepts take on a real meaning, and there are tangible rewards for tinkering with these concepts.

I am personally convinced that a year of making self-designed computer games (or any number of other hands-on activities) would be a superior replacement for the pre-algebra classes that are taught to middle schoolers. I’d also like to see a multitude of math-related classes offered as electives in high school, much as students in some schools have an option of choosing a foreign language or sport. This would be better than the current system which requires a specific sequence of algebra, geometry, trigonometry and calculus. The cynic in me doubts that we will soon see a major overhaul of our math education system, it is just so well entrenched. How many teachers really have the training and enthusiasm to make self-directed learning truly effective? How many schools can afford enough Mindstorms systems for every student? Even Papert’s own website says that his methods are "too far ahead of the times for large-scale implementation."

Fortunately, as parents, large-scale implementation isn’t a prerequisite. Any time you create a situation in which your child needs math to accomplish something desirable, like making a robot, or a videogame, or a model airplane, you are taking your kid a little closer to Mathland. And that’s an amazing place to be.