In a story that ran Monday called “Old School Dungeons & Dragons: Wizards of the Coast’s Problem Child,” posted by our friends at BoingBoing, writer Peter Bebergal posits this idea:

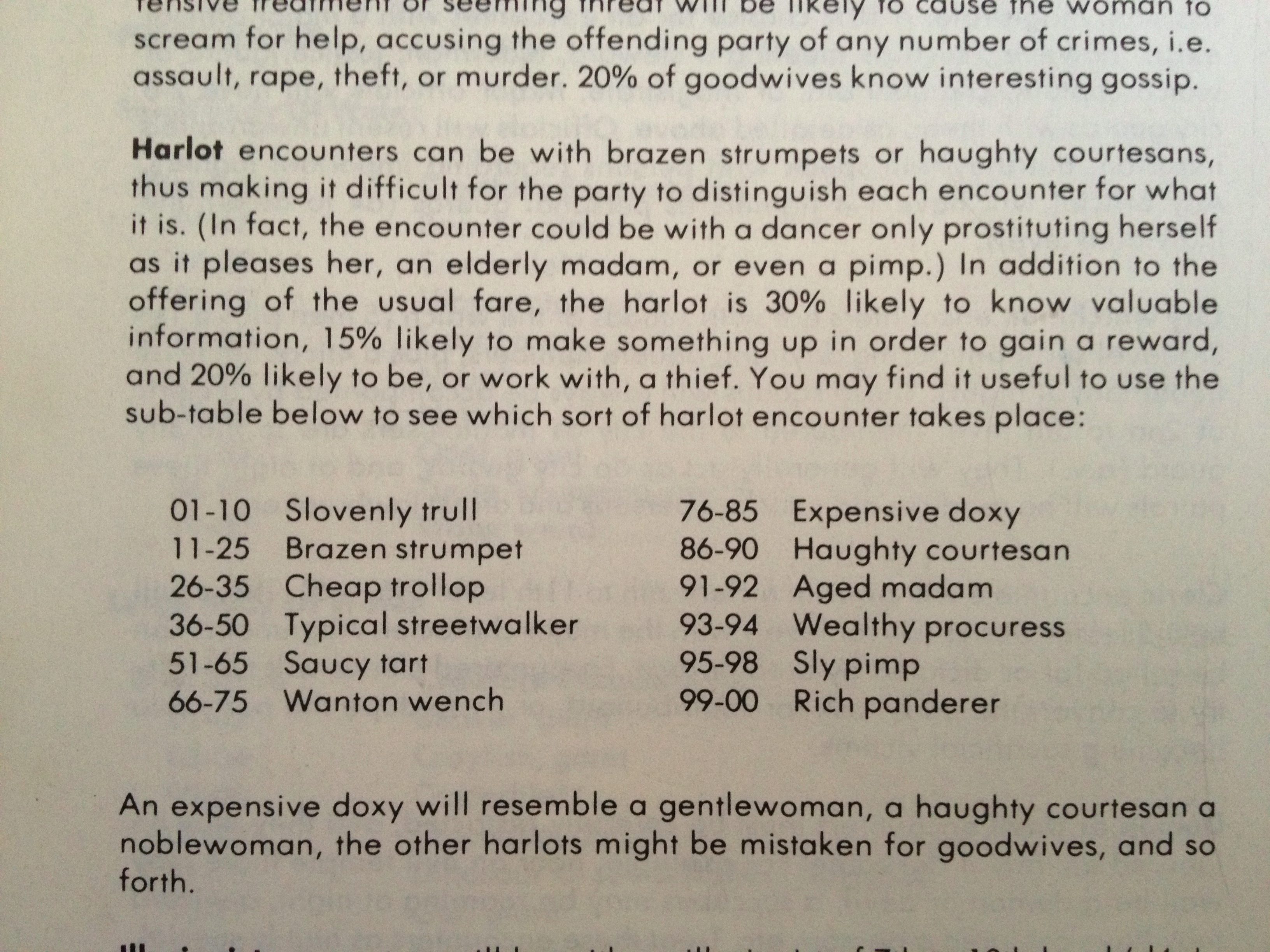

Over time, the rules governing [the] classic role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons changed and took on a weight of their own. Role-playing elements sank into a mire of charts and tables and special abilities. … Dungeons & Dragons has become a game preferring combat to role-playing. It favors prefab characters acquiring new skills and powers over a character that the player comes to identify with.

In defense of the old school renaissance of gamers who play older versions of D&D, Bebergal (who is a friend and writer colleague of mine, and a fellow gamer) rightly says he can’t be sure how Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, the game’s creators, “meant the game to be played, but they certainly invented a game that never makes us feel like we are cheating for not adhering to every table and chart.”

It’s an excellent issue Bebergal raises, this question of rules. How many or how few rules make for good game play? We want certain rules in certain games to be rock-solid and immovable. In other games, perhaps there’s some wiggle-room.

Less complex games—for example, non-role-playing games like Monopoly or Scrabble—seem by design to require the strictest adherence to rules. What few rules these games have must be followed, or all hell and chaos breaks loose, right? People throwing tiles and hotels and little metal top hats and dogs at each other. Total mayhem. We don’t want that.

Or perhaps even these simpler games could be looser. Could one play a modified version of Monopoly where the poor win and the rich lose? Or a “rules-lite” version of Scrabble that allows any word, even imaginary words, to be placed on the board, as long as the player can pronounce the word or come up with a definition for it? (See, I just made up a new rule. Damn.)

I recently played a terrific game called Tell Tale with my 6-year-old nephew, my 65-year-old step mother (his grandmother), and my girlfriend. The rules are incredible simple: images on cards serve as prompts to help a group of players tell a collaborative story (or storyboard). The very lack of complex rules not only makes it easy for the whole family to play, but there’s very little disagreement or argument or confusion. The clear point is story, and silliness, not adherence to rules. Or winning.

D&D (and other RPGs) would seem offer the greatest openness about how to play the game, and that’s true. Taken as a whole, the many versions of the game offer one of the more flexible rules systems out there. Probably the variety of D&D’s versions accounts for this. Parker Brothers doesn’t tend to reissue old games with new rules; they update the look and feel of their games, and the packaging, but tend to keep the gameplay more or less the same. I don’t hear old school Monopoly players complain about Star Wars Monopoly or Kardashian Monopoly (but then again, I’m not tapped into that subculture.)

But paradoxically, because of the many possible rule sets one can use, with D&D we see the greatest passion about how the game should be played. If you sit down with two different D&D groups, you can guarantee widely—and wildly—different interpretations of the rules, not to mention a heated argument over which version is best. Should the emphasis be placed on role-playing, and on-the-fly improvisation, and good game mastering to keep the fun going strong? Or does the group prefer orthodox adherence to feats, rounds, to hit charts or other minutiae, focusing on battle tactics over character interaction and story?

These debates are never resolved, because in the end, this is a matter of taste. But Bebergal does raise this final, and I think, worthy idea to ponder: do more rules necessarily mean “less wonder, less imagination”?

I don’t have all the answers. But clearly, the question matters if, in a game, what you value is imagination. How do rules inhibit imaginative game play? How do they make it better? And do D&D’s various rules themselves—Basic or AD&D or Expert or 3.0 or 3.5 or 4.0—tend favor or create conditions for a certain kind of gameplay to the exclusion of others? I’d love to get your responses and comments below.

Look at one of the worlds oldest games; Chess. It is bound by rules that are black and white, literally and figuratively. There is no grey area. A rook can move in a straight line only, a king can only move one spot at a time, except when castling, but that also is defined by the rules. The game would seem too rigid due to all the rules and their lack of flexibility, yet it is possibly the worlds most popular game.

Now look at Calvinball. There is one rule; you can never play it the same way twice. This leads to endless fun with nary a winner to be found. The imagination is the only referee in the game.

D&D seems to be the middle ground in this case. While the rules lend a base for the players to follow, a good DM knows that such rules are just guidelines. An overly stringent adherence to the rules limits the possibilities of game-play. Now, seeing as this is a fantasy game, there should be few limits placed on the players. All the new books with their feats and such are just WOTC putting a name on what the players have been doing since the games inception.

When I was playing and the party faced a foe beyond our ability, I grabbed the creature and jumped off a cliff. My act of self-sacrifice saved the group, but I plunged to my own death along with the creature…or did I? It seems a ring I found days before was in actuality a Ring of Regeneration. The rules stated that it wouldn’t bring you back from the dead..yet the DM knew that my surviving the fall would be more fun and lead to a legend being born. The rules were bent slightly in my favor. After all, we all know the best part of D&D is the storytelling during the game and long after the game has ended.

In answer to your question, rules should be used as a guideline; to enhance rather than limit the fun. The current state of the rules lend the game to a more min/max type of player and character. Rather that find a fun way to play a character, the player is looking for what Feats work best together to make him a more efficient monster killing, treasure-finding machine.

The rules are a foundation for game-play, not to be used as every single support beam in the structure of the game. We have enough rules in our lives everyday, without bringing them into our fantasy worlds.

This of course depends on the players and the game. In the example above using chess, if you bend the rules then you are no longer playing chess in the classic sense and now you are playing your own game.

The reason we have rules is for fairness and continuity between players and across encounters. A DM that takes liberty with the rules must be careful not to show favoritism towards a player or towards his dungeon creation. Again, in the example above if one player can cheat death, then what happens with the next player who meets his demise? Can that player then claim unfairness?

Storytelling is ultimately the goal, but if players don’t feel a sense of accomplishment due to arbitrary rule making then the story is lost.

I think a better scenario with sacrificing the character above would be that the group must go on a quest to raise the character by helping a cleric with that ability or raising the money.

Rules matter. Rules matter a lot. Rules are the players’ interface with the GM’s game world. I run some of the heavier games gleefully, and some of the lighter ones, too… but far more important than the rules’ weight is their consistency and clarity.

A bad mechanic, if consistently applied and clearly written, much easier to run and play than an inconsistent game with better rules presented poorly and using 5 different mechanics. Palladium is easier to run than, say, AD&D… it’s not that Palladium is any more realistic, nor any better at enforcing the genre, but it is a heck of a lot more consistent, with only two basic mechanics (Strike/Dodge/Parry/Roll checks, Skill tests) instead of AD&D’s 5+ (To-hit, Thief skills, Saving Throws, Proficiency Checks, Surprise Checks, Moral Checks, Turning Checks). D&D enforces the genre better, but Palladium is easier to run well. Palladium isn’t much better written even than AD&D, its benefit being simplicity.

Clarity is important, too – unclear mechanics make it harder for players to go from one game group to another using the same game, as each is more likely to have interpreted it differently.Moldvay/Cook B/X is far more player-portable than AD&D, simply because it’s more clear, and thus subject to less variety of interpretation.

Hell, the surest sign that Rules Matter is the incredible variety of games out there!