What is the future of role-playing games?

What value does a game like Dungeons & Dragons have in the digital age? How can D&D and other RPGs compete with electronic gaming — or perhaps they should not try to compete at all? And can D&D still change lives, the way D&D changed my life?

The editors of the newly launched Gygax Magazine asked me to contribute my thoughts on these questions in an essay for their debut issue, #1, which appeared in January. My contribution, “The Future of Tabletop Gaming,” is reprinted below.

Gygax Magazine is a publication that resurrects the spirit of great tabletop gaming magazines such as Dragon and White Dwarf. Its arrival is part of larger surge of interest in retro RPGs that includes the relaunch of the TSR brand, the re-release classic gaming products by Wizards the Coast, and other evidence pointing towards a resurgence in tabletop RPGs.

[NOTE: You can read all about Gygax Magazine, who’s behind it, submission guidelines, and how to purchase a copy (both print version and PDF), on their newly revamped website. My essay is reprinted below with the permission of this fine magazine, which deserves the support of anyone interested in preserving non-electronic, dice-powered, tabletop role-playing games.]

* * * * * * *

The Future of D&D and Tabletop Gaming

Before the Internet. Before cell phones, smart phones and other mobile devices. Before the proliferation of video games. Before the world got complicated.

I am tempted to say it was a simpler time then, in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when I first learned to play Dungeons & Dragons, and other role-playing games. But we know that no time is ever simple.

So perhaps it is more accurate to say that those days were an easier time. Easier to be entranced. Easier to commit to a passion. Easier to suspend one’s disbelief, and to be obsessed. Easier to be fully engaged in an activity like D&D, which requires a significant rallying of various forces: imagination, creativity, focus, and that most precious of resources, hours of your day or night. Your time.

Because who has time today? No one, it seems. We are all so busy.

Now that D&D is on the cusp of celebrating its 40th birthday (the groundbreaking game was brought into this world in 1974), and now that we can say D&D has touched at least two generations of players, its quiet shock wave coming to affect nearly every node of geek and pop culture, the time has come to reflect on its legacy. And the publication of this debut issue of Gygax Magazine strikes me as an opportunity to evaluate the role of D&D and other RPGs in the digital age. (Note: From here on out, when I write “D&D,” let that abbreviation stand for whatever similar game strikes sparks of recognition in your brain: Dungeons & Dragons, Gamma World, Boot Hill, Empire of the Petal Throne, Vampire: The Masquerade, Pathfinder, etc.)

To explore the present place of D&D in our culture, and its possible future, let us examine the past. To tell this story, we must set the way-back machine to the 1970s, AKA, the hangover from the Sixties.

All that hope of societal change and interplanetary exploration was tossed out with assassinations, violence and war. Nixon resigned, rock began to die and disco rose. Evel Knievel stunt-cycled himself across the decade. Those seismic shifts in the culture echoing from the counterculture brought us nostalgic time-trips called Happy Days and Little House on the Prairie, the quasi-conspiratorial Six Million Dollar Man and the wish-fulfillment fancy of Fantasy Island.

The early Seventies opened minds to role-playing, trying out new clothes, new ways of living. Drugs, psychedelia, and heavy metal suggested the presence of other worlds. Led Zeppelin wrote of Middle-earth as if it was a real place, to which they had recently adventured.

The era was ripe for D&D.

* * *

In my experience of the 1970s, as someone who witnessed all these shiftings as a kid, the era was marked by unbridled downtime. Bored time. Waiting time. Waiting for a parent to come home, or to be picked up by a parent, or for a parent to finish an adult activity.

Of course, there were no cell phones. No iPads. To check in with home base, you’d call from a friend’s house, if you called at all. If you were in town or at the mall, you’d call from a payphone. If you ran out of quarters, you were stuck. Therefore, I spent many hours alone, indoors, and roaming the outdoors: biking, swimming and sledding unsupervised, and exploring the hundreds of acres of woods, streams, bogs and sandpits that surrounded my house. I walked barefoot. I built tree forts. I played with firecrackers and model planes and Lego. I didn’t wear a helmet.

And I read a lot of books: The Great Brain, Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, Encyclopedia Brown, My Side of the Mountain. Books with child and teen (or rodent) protagonists going on adventures. No soccer practice. No violin lessons. No being shuttled about endlessly to after school programs of questionable merit. I was trained to make my own fun.

In those days, the reach of the entertainment-media complex was limited. Nothing could quite absorb our time and brain-scape the way computers and video games do today. The present-day avenues for escape we now accept as the new normal, and real, were limited. VCRs, movie rentals, home video games and PCs were only in their infancy. Other than books, of course, only TV could divert and colonize your mind, for hours on end. But the quality and verisimilitude of these visual media were lacking. Special effects seemed primitive, but our bar for believing was also set lower. Net effect: The imagination was better. Imagination was still king.

Even before I stumbled upon D&D, I had begun to teach myself the tools of storytelling. In addition to trash TV after-school re-runs, I was raised on a steady diet of Creature Double Feature, a Saturday afternoon monster movie program slotted right after the Saturday morning cartoons. I learned, via osmosis, how to extend the stories in my mind. I could conjure legions of reanimated corpses that would, clearly, one day, erupt from the local cemetery. I would scheme the movements of giant, irradiated ants that would crush our town. Even before I learned about D&D, I’d narrate the story of how my friends and I would defeat them all, and restore order to our little world. All of these creatures and plots and imagined gore and destruction would happily infect that murky dreamspace between play and the real world, between faint TV signals and our vivid imaginations. The realm of the possible sometimes felt more real than reality itself.

A product of all these influences — lackadaisical supervision, weird pop culture, a penchant for fantasizing — I was being primed for geekdom by some secret force. Then came the summer of 1977. I was 10, going on 11, when I saw Star Wars in the theater. My eyes were blasted open opened. What was this? A teenager, Luke Skywalker, on another planet who had some mysterious destiny to face and fulfill? And he got to dog-fight in spaceships? And swing a light saber? And hang out with robot sidekicks? Whoa. I remember staying up late after seeing Star Wars, feverishly drawing space ships. Suddenly, I wanted to be a filmmaker. A storyteller. I began to dream big. In 1978, I saw Ralph Bakshi’s ill-fated, animated adaption of The Lord of the Rings — like Star Wars, also cutting-edge in its use of technology and special effects.

As I said, in many ways it was an easier age — easier to believe in flights of fantasy. Suddenly, fantasy felt real. Physical. Palpable. Experienced.

Then came D&D.

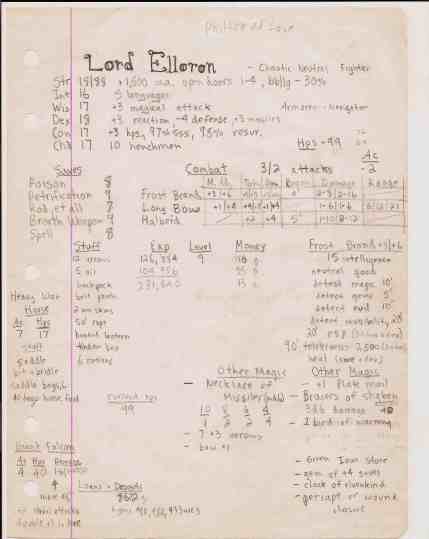

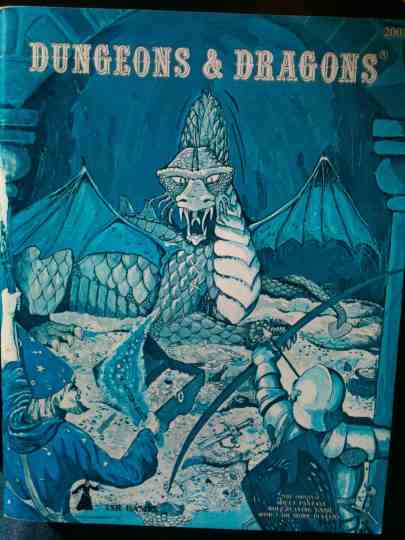

I was first introduced to D&D in 1979, by my next-door neighbor. Recall, there was no D&D wiki to consult. There were no online communities to connect me to some exterior support group. There was simply a D&D Basic boxed set, or a stack of AD&D tomes, and a friend who explained what this new and strange and wondrous game was and how to play it. And play I did. I consumed the game, and it rapidly consumed me. My susceptibility to D&D was also encouraged by near-fatal character flaws: I was shy, introverted, and otherwise anti-social. I was raised in an emotionally treacherous home whose foundations seemed to be disintegrating around me. I needed a focus, a place to become lost, to become obsessed by a single thing. D&D, the ultimate combination of reading, storytelling, drawing, fantasy, geek knowledge and imagination, was the clincher. I was hooked.

I was also yearning to belong to a gang, a group, a team of my own people. To win. I finally did. I played a lot of D&D. I found my first fellowship of friends. I began to socialize. We played every Friday night from 5pm to 11pm, eighth grade till senior year in high school. From 1979 to 1984, I was under D&D’s spell. Me and the other members of our “D&D gang,” we quickly grew accustomed to this idea of role-playing different, more daring versions of our selves. By becoming these characters — sneaky hobbits and stalwart paladins and fire-wielding wizards — we were in control. Like actors in a play, our little band of nerds could do things in-game we only dreamed of in real life.

But beyond its psychological and social benefits, D&D almost felt subversive. In a world whose technologies were about to bring untold wealth of visual stimuli (harbinger of things to come: during this time, my buddies and I were also learning to crudely program our school’s TRS-80 computers), D&D offered and still offers a radical counter-attack.

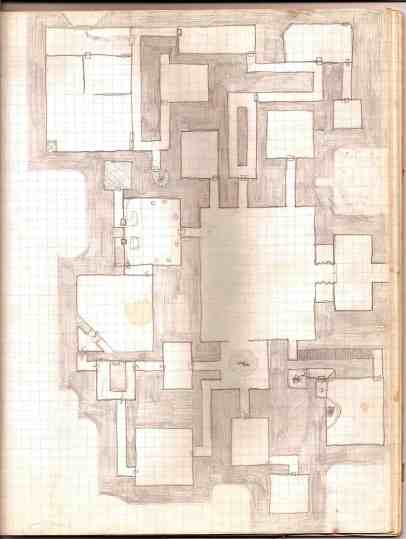

You work with paper and pencils, not pixels. Imagination is the play-scape, assisted by graph paper maps, miniature figurines of orcs and hobbits, and an impartial referee called a “dungeon master” who moderates an improvisational story with a group pretending to be a fellowship of dwarven warriors and half-elf wizards. Players toss polyhedral dice and consult tomes of rules to determine outcomes of actions. Like in life, what you could do in-game is determined by a set of fantasy rules — and the roll of the dice. There are rules, but also chance. Roll a 20 on a 20-sided die and even if you are a lowly first-level fighter, you might strike a death-blow to a powerful foe like a dragon.

There is no uniform. No local business needs to sponsor your D&D group. There are no cheerleaders, and no instant replay.

My world at home was careening out of control. But in the world of D&D, there was hope. D&D let me feel powerful. My buddies and I, we spent a lot of time in our bedrooms, playing with our, ahem dice. We did our time in the dungeon. And we began to feel a little badass. At the time, D&D was even a threat to the youth and mortal souls of American youth. Religious conservatives were convinced the game turned players into suicide-prone devil-worshippers. Which meant D&D, like countless social forces before it — the telephone, comic books, rock music, heavy metal — had become a threat to the status quo. Which meant the game had arrived, and fought, and conquered.

* * *

Like most fads, D&D went from being the “hot” Christmas gift that many American boys (and sadly, it was mostly boys) desired in the 1980s, to falling out favor. Arcade video games like Asteroids, Defender, Galaga and Robotron: 2084, and computer games like Zork, Zelda, Quake and Doom, began to replace D&D as go-to escapes. In the late 1990s came the Internet. Then came Nintendo. We know this history.

And so a prehistoric paper and pencil game like D&D shouldn’t survive in this age of digital media, right? Who wants to spent hours scrawling dungeons in graphite on aqua graph paper and dreaming up elaborate backstories to kingdoms and curses, when endless imaginative realms are available off the shelf, plug and play? Now we can consume any narrative we want at light speed — via cable, DVD, Netflix, YouTube, Hulu — on our theater-quality flat screens, even in 3D. Video game platforms have become as commonplace as the card tables and Monopoly boards of yore. Via the Wii, families bowl and snowboard and sing karaoke together. How can D&D compete against all this digital eye candy? On superficial terms, of course it can’t. That’s why the direct reach and sales of D&D and similar fantasy RPGs peaked in the 1980s and early 1990s, just as digital culture spread like a pox across the land.

Yet, Dungeons & Dragons and its ilk left their mark, I would argue, carving a huge gaping channel connecting myriad waterways of entertainment media. Since its birth in 1974, an estimated 20 million people have played D&D and spent $1 billion on its products. Many former players have gone on to become titans of Hollywood and explorers of Silicon Valley. Virtually every computer coder once dabbled in the game. Which explains why so many video games use a “run through a dungeon and kill monsters” premise, and borrow the open-ended storytelling concepts pioneered by D&D. The tropes of leveling-up, collecting experience points, and role-playing a character or avatar — “Ha! I will strike the She-orc with my +3 broad sword!” — have formed the foundation of virtually every video game on the market. Without tabletop RPGs, MMOs would not exist (nor would Angry Birds). We would not have Facebook or online dating — all popular and diluted forms of role-playing — were it not for D&D. Ahead of many other forms of entertainment, D&D blazed the trail through dungeons dark, helping making make the world safe for fantasy and geek culture, Harry Potter and The Lord of the Rings.

From the fringes, D&D shot out its tendrils. Now that generation of former players has grown up, and they’ve come out of the basement to attest to D&D powers. Film director Jon Favreau, professional basketball player Tim Duncan, and comedian Stephen Colbert are among those who once played; actors Vin Diesel and Wil Wheaton still play; and all profess the positive impact of D&D on their creative souls.

The game can be seen as a common “nerd experience” that taught millions of geeks to socialize, empathize, level-up (in game and in real life) and emerge from the basements of their solitude to tell heroic stories. Now in their 30s, 40s and 50s, these geeks have shown their quality. They forge and hew the media you now consume: movies, television, music, novels, art and, of course, video games. D&D was like crack for creative people: artists, writers, performers, musicians, filmmakers and poets all drawing from its waters. They are the generation of creators now telling the biggest stories. And for that, they’re thanking D&D.

As one gamer told me, “D&D is the secret handshake in Hollywood today.”

* * *

Which brings us to the present of RPGs. And the future.

At times, I worry. D&D taught me so much. Do video games also teach the same imagination and storytelling to kids, teens and college aged-folk — the sweet-spot demographic that has always formed the core of D&D players? Can they muster the skills of time and imagination in an age that succeeds in distracting us from what matters and from each other?

I am trying not to be simply nostalgic for a lost age. I didn’t play D&D for a while — some 25 years — but now, at age 45, I’m playing again. My experience of D&D isn’t simply a memory, and I keep that nostalgia largely at bay. (And, incidentally, I play D&D with local friends but also one via Skype who lives three times zones away, and sometimes we text each other during the game, and check email. We are not pure.)

While I still play, I am reminded of what value the game has and can still have in the digital age. To my mind, all this make-believe derring-do and heroic yarn-spinning can actually be a transformative act.

For one, D&D changes lives. As a kid, I was not only teaching myself shoddy draftsmanship and baby-step acting. I also learned to be social, collaborative and to create community. What a foreign feeling that was, to be part of a gang of guys who got me. Strength in numbers. Suddenly, I wasn’t alone. My days crawling in dungeons had actually taught me how to have friends. I learned how to be a leader. How to be curious, and interested in history, languages, cultures, puzzles. How to empathize and negotiate with “the other,” those not like me: orcs, elves, tavern keepers, undead kings, jocks and prom queens. How to think creatively, solve problems, figure things out, think out of the box. How to manage and predict. How to organize and plan. D&D is about achieving a mutual and collaborative goal and being part of a collective experience. You can’t help but feel camaraderie, fellowship, and belonging — the things I needed most as a shy, self-conscious kid who was not about to get those experiences from other, more macho activities like team sports.

Thinking back on the hundreds of hours spent in the thrall of D&D, I am reminded of a part of my creative imagination that I lost touch with along the way — the idea that you make your own entertainment.

D&D remains a do-it-yourself, low-tech, largely non commercial pastime. You don’t need gadgets or expensive equipment. The game doesn’t burn electricity or gas or batteries. No monthly fees or (un)necessary upgrades. You’re forced to interact with each other, to be present and face-to-face (not face in our iPhones or screens). With D&D, all you need is some dice, graph paper, some rule books, some pencils, and some provisions. In this way, D&D is a subversive, even revolutionary, fight against the status quo of entertainment in America.

In a world where we are inundated with innumerable pleas to buy the latest technologies, and ways to spend our time and money to be entertained, RPGs represent a realm mostly free from corporate influences, marketing pitches and merchandizing. You’re not consuming or passively watching some story on TV or at the movies. You make the game yourself. You must create. You draw, sketch, map, plot. You and your friends generate a fantasy experience rather than merely absorb one. It’s you who tells the story. D&D still lingers in the culture, I think, because it’s a crucial link to other individualized, user-driven, human-scaled creative spaces separate from the intrusion of commercial forces.

All this is hugely important, and immeasurably powerful. And for these reasons, I am hopefully about the future of D&D and other table-top role-playing games. Self-publishing and internet distribution means more gaming products are available than ever before. Is some of the merchandise borderline gimmicky, or even desperate to lure those addicted to screen, such as virtual tabletops and other digital geegaws? Sure. But by and large, I think we’re experiencing a quiet renaissance in tabletop games. Partly, this is being driven by 30- and 40-something former gamers (like myself) feeling a desire to reclaim some aspect of their younger, gamer selves and in-game heroics. Or they have children and want to pass on that gaming experience to their offspring.

Also driving the surge is our reaction to the impersonality of technology. The more we feel trapped by our computers and wifi connections, the more we will crave “real,” face-to-face experiences — and, ironically, fantasy games can sate this desire. Just look at the widespread acceptance and popularity of LARPing, fan fiction, costuming and cosplay, Ren faires, and other hobbies that are as much about hanging out and talking as they are about crafting something real.

The best news for adult gamers is that grown-ups can often do a better job playing D&D than teens. Back in the day, me and my gaming buddies, we fought about rules. A lot. I recall many a power struggle as we grappled with becoming young men — like jocky antics on the football field, we indulged ourselves in trash talking, the equivalent of endless arguments over who was safe and who was out, except with about 10 hardcovers as the umpire’s rulebooks. Now as an adult player, I can just enjoy the story and the adventure. I’m less persnickety about the rules, or who is right and who is wrong. I want to simply get lost in the narrative.

Is it harder to find time for that weekly game night, that uninterrupted, immersive, six-hour block of time I once had? Sure. But when I (and the other members of my group) can find it, D&D helps me recapture something I lost — that open ended, anything can happen experience. Grown-ups don’t often get to be creative in this way, nor to have this kind of free-range fun anymore. D&D matters today because it’s really one of the few activities left that lets us all be storytellers and reunites us with our storytelling pasts. I don’t want to imagine a world without self-made story. Without heroes. A world where only Hollywood tells us how we can have a good time. I love Peter Jackson’s vision, and I am as entranced by immersive games like Skyrim as the next geek, but it’s essential to recognize what these movies and games also take from us.

D&D will survive because it taps into humankind’s innate sense of wonder, its thirst for danger, and its curiosity about magic, dark forces and the unknown. The what is not there. The what cannot be explained. The what should not be possible. On our real world, where else is there to explore? Google Earth and science explain every square foot of every mystery. Like religion, D&D says there’s still unexplained phenomena in the world. And, even if it’s an imaginary world, you still have a role to play. To be the hero, to have a fate and an imprint bigger than you’d have in the real life. And maybe, once you’ve ended the game session, you’l feel more heroic in the so-called real world.

I leave you with this final thought: To keep Dungeons & Dragons alive and kicking, adult games need to pass its skills, its feats, and its power strikes onto the next generation. Make your kids put down their devices. Tell them a story, and how to tell stories. Teach your children that what happens in their minds is more powerful than anything Warner Bros., Electronic Arts or Apple can throw at them. Because in D&D, that story also takes place in the collective minds of those gathered around a table, a pile of dice and a bowl of Cheetos.

I thought I was reading about myself!

Me too!! Sounded a lot like me except 5 years younger!!

Great piece. Bringing RPG’s into the modern context. But not to be forgotten was the fact that it became an international phenomenon just at a time when international communities were about to take off via improved telecommunication and the internet. Mike Horton, UK

I think the future lies partly with online community hubs like http://www.thetangledweb.net that offer online character sheets, dice rollers and support play by post or the use of various virtual table tops

If you want to give it a try visit http://www.macrayskeep.com It is not a place to talk about playing D&D it is a place to actually play D&D.

One thing that it will still be a long, long time before digital gaming will be able to come close to duplicating is the ability to do ANYTHING like you can in a tabletop RPG. There are always rules and restrictions because of the conventions of the game. Video games force you into a certain world of impermeable rules, Further, it is hard to get the same kind of bond with a video game character as one can with one’s RPG character. My memories of video games are not nearly as strong as the memories of my misadventures (and adventures) in one RPG or another.

The lasting impression that D&D leaves, along with other games, will depend on our overall cultural memory and how much damage to the credibility the quest for dollars has on the industry. I have seen WOTC, Microsoft, and others devastate some aspects (such as miniatures) for profit. Government and social protectionism ( we must ban this because some one might be stupid) also press to damage the industry. Game companies started major revisions in about 2001 which caused a spike then plummet in sales and interest, now those which survived are producing “classic” reprints of earlier rules-sets while continuing to produce badly designed new versions. This is where the question truly applies can non electronic gaming survive the current pattern of self destruction which seems to have become endemic to our social culture.

Really, really awesome read. Thank you for writing this.